Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

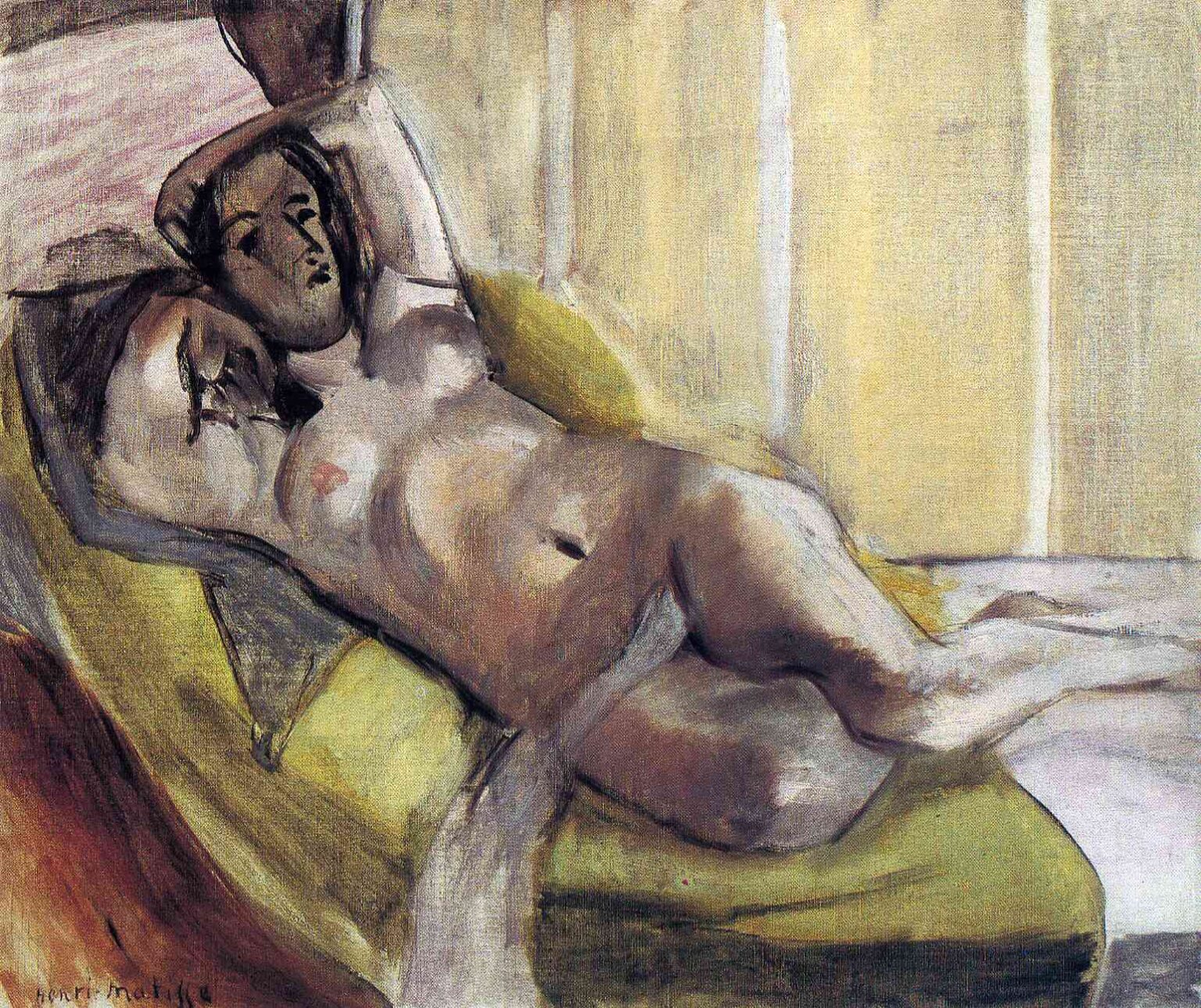

Henri Matisse’s “Nude Reclining on a Sofa” (1923) belongs to the heart of his Nice period yet feels strikingly different from the jeweled odalisques and floral interiors that often define those years. Instead of bright carpets, Moorish screens, and sunlit blues, the painter offers a pared-down chamber where a single figure stretches diagonally across a sofa, her body modeled in subdued greys, mauves, and ochres. The composition trades spectacle for quiet intensity. Matisse compresses space, slows color, and lets drawing and touch carry the drama. What emerges is a lesson in how a modern painter can honor the classical reclining nude while reinventing its language through restraint.

A Classic Theme Recast in a Modern Key

The recumbent female nude is a lineage that runs from Titian’s “Venus of Urbino” to Ingres’s “Grande Odalisque” and Manet’s “Olympia.” Matisse knew this tradition well, but by 1923 he had learned to separate the subject’s historical baggage from his own pictorial aims. Here there is no goddess, courtesan, or salon provocation—no voyeuristic exchange, no symbolic accessory. The figure is simply present, her hands lifting behind her head, her legs easing into the cushion’s slope. Matisse’s allegiance is not to narrative but to equilibrium. The body becomes a structure—a set of measured planes and curves—through which light, tone, and touch can be tuned to a heightened calm.

Composition and the Diagonal of Repose

The painting is organized around a long diagonal that runs from the model’s raised forearms at the upper left to the extended feet near the lower right. This diagonal is crucial: it converts repose into movement felt across the surface, guiding the eye in a sustained glide from head to heel. The sofa’s cushions answer this line with softer, interlacing diagonals—one wedge pushing up under the shoulder, another cradling the hip—so that figure and furniture lock into a single, stable geometry. Vertical accents in the background—pale bands that may indicate wall panels or light slicing through curtains—keep the diagonal from floating, providing a quiet counter-rhythm that steadies the gaze.

Tones, Not Spectacle: A Different Nice Palette

Viewers who expect Nice-period fireworks are surprised by the palette: muted greys, dusty violets, olive and straw, flesh tones dipping toward pearl and taupe. Rather than flooding the room with chroma, Matisse builds a low, resonant chord. The cooler violets temper warmth in the abdomen and thigh; the olive cushions cast a vegetative glow that makes the skin feel luminous by contrast; the background’s parchment verticals ventilate the field without pushing it into depth. The whole surface reads as a single climate—late afternoon in a shaded room—where color is more breath than proclamation.

Drawing with Planes

Matisse’s drawing here is sculptural and laconic. He models with large planes, not with tight contours. The cheek is a single cool facet turning from the darker mask of hair; the sternum catches a pale rhomboid of light; the ribcage is a broad oval gently lifted by breath. The pelvis, notoriously difficult to render without stiffness, is handled with two intersecting arcs: one that carries from the navel to the hip crest, another that slides into the upper thigh. Hands and feet are summarized with the fewest strokes that will hold the pose—enough suggestion to convince, not enough detail to distract. The face is reduced to essential notes—brow, nose bridge, eye hollows, a small closed mouth—so that it participates in the same language of planes as the torso.

Brushwork and the Sensation of Flesh

The surface is alive with varied touch. On the torso and thigh the paint thins, letting the ground flicker through and allowing successive passes to veil one another like layers of skin. Around the shoulder and hip he uses denser, buttery strokes that sit on top of the weave; their heft suggests the pressure of body against cushion. Along the contour of the abdomen and forearm, dry-brush pullbacks leave a granular edge, a rasp that registers as warmth meeting air. None of these moves is descriptive in the academic sense; they are sensory equivalents, painterly choices that make flesh feel like flesh on a sofa rather than marble on a plinth.

Light Without Theatrics

Light arrives as a surrounding presence rather than as a spotlight. There is no cast shadow slicing across the form to create drama; instead, value shifts are mellow and continuous. The fullest lights skim the shoulder blade, breast, and outer thigh; the gentlest shadows pool under the ribs, at the inner elbow, and along the groin. These soft transitions are vital to the painting’s tone. They keep the figure breathing and keep the eye sliding rather than jolting. The effect is like listening to a slow legato line after the staccato sparkle of Matisse’s florid interiors.

Space as a Shallow Chamber

Matisse builds space by compression rather than recessional depth. Foreground: the couch’s green slopes and the left-hand bank of cushion. Middle: the body bridging corner to corner. Background: a set of pale verticals that read more as panels of color than as architecture. Overlaps make the distances legible, but nothing tunnels away. This shallow construction brings the viewer close, as though seated beside the sofa, sharing the same still air. It also preserves the modern surface: everything remains undeniably paint, even as it persuades us of bodies and pillows.

The Sofa as Counter-Form

The furniture is not a setting; it is a partner. Each cushion is a counter-form to a bodily mass: wedge for shoulder, cradle for hip, ramp for thigh. Its greens and ochres form the middle register in the color chord, holding the cooler background and warmer flesh in sympathy. The sofa’s edges are drawn with a loose, elastic line that sometimes doubles or frays, an honesty about looking and adjusting that keeps the arrangement alive. By granting the sofa this degree of agency, Matisse continues his Nice-period “democracy of surfaces,” where human and décor share equal pictorial dignity.

Eroticism Held in Check

The painting is undeniably sensual—the open torso, the relaxed spread of limbs, the sheet tossed across the lower abdomen—but the tone is not prurient. Matisse continually redirects the viewer from explicitness to rhythm: from nipple to the oval of the ribcage, from pubic triangle to the broad gradient of thigh, from parted lips to the measured scaffold of cheek and brow. The erotic becomes formal pleasure, a satisfaction of harmonies rather than an anecdote of desire. This cooling of heat is typical of the Nice period at its most mature. It’s not a denial of the body; it’s a transposition of the body into painting’s key.

A Quiet Dialogue with the Odalisques

Seen alongside contemporary odalisques posed in striped chairs and before patterned screens, this canvas feels like the afterimage left when ornament is removed. The interior has been emptied to essentials so that the same pictorial problems—how to balance planes, how to tune warm and cool, how to use line sparingly—can be solved under stricter constraints. What remains from the odalisque world is the ideal of repose and the sense that domestic comfort can be a stage for beauty. What disappears is narrative exotica. The result is deeper intimacy: the painting is less about a theme and more about a body at rest becoming a formal melody.

The Face as a Mask of Rest

The head, tilted back and cushioned by the raised forearm, has the quiet of a theater mask between expressions. Matisse abstains from psychological cueing: the eyes are lowered or closed, the mouth neutrally sealed, the brows long and level. This restraint protects the painting from story. Instead, the face functions as a tonal hub. Its darks anchor the lighter torso; its small planes echo the larger planes of chest and belly; its compact oval recapitulates the big ellipses of cushion and hip. The head is not a portrait; it is a chord tone resolving the whole.

Rhythm, Interval, and the Music of Looking

Everything in the painting participates in rhythm. The diagonal trunk is a long sustained note; the repeating verticals behind are slow bar lines; short accents—elbow, knee, heel—punctuate the phrase. The narrow sash or strip of cloth that runs down the abdomen acts like a glissando, a visual slide that clarifies the body’s twist from rib to pelvis. Even the small, darker triangle at the pubis is handled as an interval in the larger cadence, neither hidden nor spotlighted. This rhythmic clarity invites a particular tempo of looking: slow, continuous, and returned—exactly the tempo that reveals the painting’s subtleties.

Material Presence and the Trace of Time

While the surface feels fresh, there are places—especially in the background and along some contours—where earlier decisions show through: pentimenti at the hip, a softened boundary near the knee, thin scumbles that almost polish the canvas. These traces record time spent adjusting the pose’s weight and the sofa’s counterweight. The painting’s calm is therefore earned; it is the residue of many small calibrations that now read as inevitability.

Connections to Older Masters

Despite its modern economy, the canvas is in conversation with long traditions. The ovoid torso and long diagonal recall Venetian handling of the reclining nude; the broad, low-key tonalities have something of Corot’s late figures; the sculptural simplification of limbs owes a debt to Ingres’s disciplined line. Yet the painting refuses historicizing detail. It remains resolutely of its moment—an early 1920s interior where the human figure is not myth but measure, not allegory but breath.

How to Look, Slowly

Enter at the left where the forearms form a cradle for the head. Let your gaze ride the shoulder’s pale arc into the shallow bowl of the breast and across the ribcage’s oval. Follow the sash’s cool streak down the abdomen to the hip crest; slow across the broad plane of the thigh; settle at the knee before gliding to ankle and heel. Pivot into the olive cushion, drift up through the muted verticals of the wall, and return along the upper arm’s darker contour to the face. With each pass, notice how warm and cool trade places, how hard edges relax into soft, and how the diagonal remains taut however long you linger.

Meaning Through Restraint

What does the painting finally propose? That serenity need not be empty, that a reduced palette can hold as much complexity as a bright one, and that the human body—taken without story—can be enough to organize a world. In a decade when Matisse often celebrated decorative abundance, “Nude Reclining on a Sofa” argues for another value: concentration. The canvas suggests a room kept quiet so that touch, plane, and tone can be heard. It invites the viewer into that quiet and rewards attention with a feeling of sufficiency.

Conclusion

“Nude Reclining on a Sofa” shows Matisse at his most distilled. The diagonal of the body, the muted chord of color, the sculptural planes, the shallow chamber, the varied touch—everything is understated yet exact. The painting absorbs the grandeur of the reclining-nude tradition and returns it in a modern whisper: a body at rest, a sofa shaping itself to her weight, and a room holding its breath. Within that whisper, an entire language of painting speaks—measured, tender, and sure.