Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

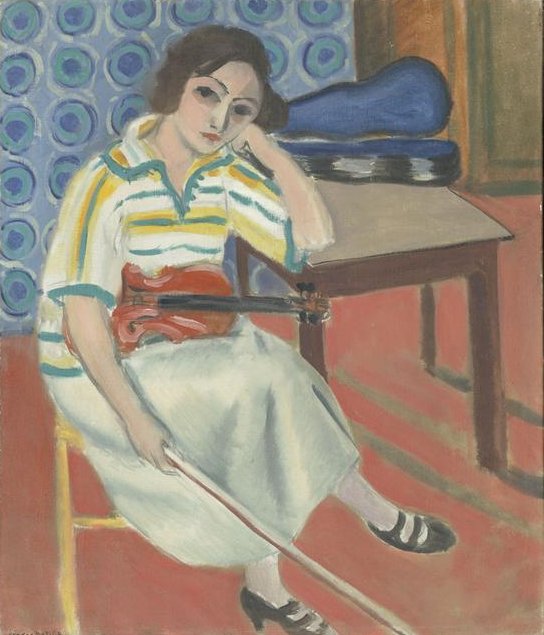

Henri Matisse’s “Woman with Violin” (1923) captures a quiet pause in a musician’s day: a seated young woman rests her cheek in her hand, bow dangling loosely while the violin lies across her lap. A blue patterned wall, a coral-red floor banded by light, and a simple table with a closed case complete the scene. It’s a small subject, yet the canvas radiates Matisse’s Nice-period clarity—color used as climate, pattern as structure, and a human presence tuned to its surroundings like an instrument to its orchestra. What appears casual becomes, on slow looking, a finely balanced meditation on attention, sound, and rest.

Historical Context

By 1923, Matisse had been working for several years in Nice, where he developed a luminous, decorative modernism distinct from the high-voltage Fauvism of his earlier career. The Nice interiors favor ambient light over theatrical shadow, shallow layered space over deep perspective, and a democratic surface where figure and décor share equal dignity. Music appears often in this decade—mandolins, guitars, sheet music—because it provided both motif and metaphor: rhythm, harmony, and tempo are pictorial problems as well as auditory ones. In “Woman with Violin,” music is present as object and implication. We feel not performance but the interval between pieces when the ear hums with what it has just heard.

Composition and the Architecture of Pause

The composition is built on a quiet triangle. The tilted head and propped elbow form the triangle’s apex; the lap and bowed legs establish its base. The bow, slipped loosely from the hand and plotting a clean diagonal toward the lower right, locks the triangle while linking figure to floor. The tabletop creates a stabilizing horizontal above the lap, and the weight of the closed case—an emphatically blue silhouette—balances the figure’s mass. Behind her, the circular rosettes of the patterned wall march in columns that echo the three yellow-green stripes on her blouse, threading background and foreground into one fabric.

The chair, glimpsed in yellow angles, is more than furniture; it’s scaffolding. Its back leg spells out a vertical that rhymes with the table’s legs and with the woman’s shin. These straight, structural notes keep the composition from dissolving into languor. Every angle is measured to convey rest, not collapse.

The Gesture and the Instrument

The violin is central but understated. Matisse refuses the virtuoso pose; the instrument lies across the abdomen like a warm pet. The left hand, freed from fingering, relaxes into the bow’s long line; the right arm, which would normally drive sound, supports the head instead. This reconfiguration is eloquent: it makes visible the off-beat in a musician’s rhythm, the private moment between practice and play. The closed case on the table underlines the pause. Its solid, matte shape—heavier than the violin’s glazed reds—temporarily silences the room. The relationship between the three “players” (woman, violin, case) is crafted like chamber music: one rests, one glows, one waits.

Color Climate

Color organizes mood and space. The coral-red floor sets a warm stage, softened by bands of light that fall diagonally and guide the gaze toward the figure. The wall’s blue field, stamped with concentric rosettes of cobalt and teal, cools the room and gives it air. The blouse—white with lemon, green, and turquoise stripes—bridges these poles, while the skirt’s pale grays calm the temperature at the center. The violin’s varnished orange-red sparks against the cool palette without bullying it; the case’s deep ultramarine answers the wall, creating a cool counterweight that keeps the floor’s warmth from dominating. Matisse uses color not as a label for objects but as a system of balances—warmth and coolness breathing in steady measure.

Pattern and the Democratic Surface

The rosette wallpaper is one of the painting’s great pleasures. Each circle, made from quick concentric strokes, is a little drumbeat. Their repetition yields a gentle, syncopated field that animates the wall without pushing it forward. Pattern here is not mere decoration; it’s the architecture of seeing. It keeps the surface unified while allowing the figure to hold the center by contrast of texture: smooth skin, satiny wood, soft cloth set against stamped rosettes and the tabletop’s matte plane. Even the striped blouse participates in this democracy of surfaces, echoing the wall while retaining its own tempo in wider, more irregular bands.

Light Without Drama

As in so many Nice-period works, illumination is ambient and humane. Light sifts through the room rather than striking it. Matisse paints it as temperature and value shifts rather than theatrical contrasts: soft violets under the jaw and arm, faint gray on the skirt’s folds, a milkier highlight along the violin’s edge. The diagonal bars of lighter coral on the floor read as sun falling through blinds or a high window, but they are not literal description so much as compositional music. These pale bands lift the floor and usher the bow toward the corner, then return the eye to the seated figure. Because the light is even, color can do the expressive work; the canvas glows instead of performing.

Space by Layers, Not Perspective

Depth is built by overlaps and color intervals rather than strict vanishing points. The table overlaps the chair; the case overlaps the table; the figure sits in front of both; the patterned wall presses forward without receding into distance. The result is a shallow stage where every element remains legible as paint. This layered approach invites intimacy: we seem to stand just inside the studio, near enough to hear the rasp of bow hair if the player lifted her arm. It also keeps the painting modern; the surface remains honest, a harmony of flat shapes rather than a peep-show into another world.

Drawing and the Economy of Means

Matisse’s drawing is famously economical. The face is constructed with a few confident arcs: a dark, enclosing hairline; sloped brows; succinct lids and pupils; a small plane for the nose; the briefest turn for the mouth. The cheek’s weight is a single soft shadow that says fatigue without melodrama. The blouse is indicated by stepped stripes and a notched collar; the skirt by big, permissive planes that leave room for light. The hands are simplified to the needs of the pose: one supports the temple, the other drops with the bow. Everywhere, contour breathes—tightening at the wrist, slackening along the skirt—so the figure reads as alive within stillness.

Brushwork and Material Presence

The surface carries the trace of how it was made. In the wall, rosettes are tamped in with loaded, circular strokes that sometimes leave a ridge at the edge. The table’s top is a single spread of cool beige; you can feel the brush’s sweep from corner to corner. The violin’s luminous reds are thin glazes that allow light to bounce through, mimicking varnish. On the skirt, softer, drier scumbles stretch across the knees, evoking cloth without describing weave. These varied touches keep the painting’s tempo audible: brisk in pattern, calm in furniture, tender in flesh.

Rhythm, Music, and Silence

Everything in the painting participates in musical metaphor. The wall’s rosettes drum softly. The floor’s diagonal lights tap time. The stripes on the blouse pulse in a measured phrase. The bow’s diagonal is a slur drawn across the composition. Yet the dominant sensation is silence—silence after sound, the kind musicians prize because it lets phrases settle in the mind. Matisse pictures that silence with remarkable tact: the slightly drooping eyelids, the relaxed bowing arm, the case shut like a rest in a score.

Emotional Tone and Modern Poise

The subject feels contemporary in its understated psychology. There’s no melodramatic narrative, no virtuoso display. The woman’s face suggests absorption rather than boredom, the posture a temporary drift rather than resignation. This is the Nice period’s ethical signature: pleasure in attention, value placed on intervals, the dignity of ordinary concentration. The painting proposes that rest is part of rhythm, that modern life—so often noisy—needs poised pauses.

Relations to Other Nice-Period Works

Compared with the odalisques of 1923, “Woman with Violin” is cooler and more intimate. It swaps theatrical textiles for one patterned wall, extravagant poses for a seated slouch. Compared with the reading and writing pictures from the same year, it shares the central theme: thought as an activity visible through posture. Where those canvases deploy books as rectangles of light, this one offers the violin—curved, varnished, ready—to represent the mind’s instrument. Across all of them, Matisse keeps the constants of the Nice vocabulary: ambient light, compressed space, ornamental order, and an economy of line that lets color carry feeling.

How to Look, Slowly

Start with the bow. Follow its pale shaft down to the corner, then let your eye rebound along the floor’s light bands to the shoes and folded skirt. Climb the violin’s red curve to the hand and up the supporting arm to the cheek. Rest at the face—brows, lids, the small red mouth—before drifting to the blue case on the table. Cross into the patterned wall and trace one column of rosettes upward until it meets the blouse’s stripes; notice how these patterns rhyme. Circle back to the bow. Each pass clarifies the system: diagonals lead, horizontals reassure, patterns keep time, and the figure holds the center like a sustained note.

Conclusion

“Woman with Violin” turns a simple pause into a complete orchestration of color, pattern, and form. The warm floor and cool wall set the climate; the table and case steady the architecture; the violin glows like a memory of sound; the bow draws a quiet diagonal through the room; and the musician’s inward gaze fixes the tempo of our looking. It is a painting about music without noise, performance without show, modern life measured not by drama but by the grace of attention. In the hands of Matisse, even rest becomes radiant.