Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

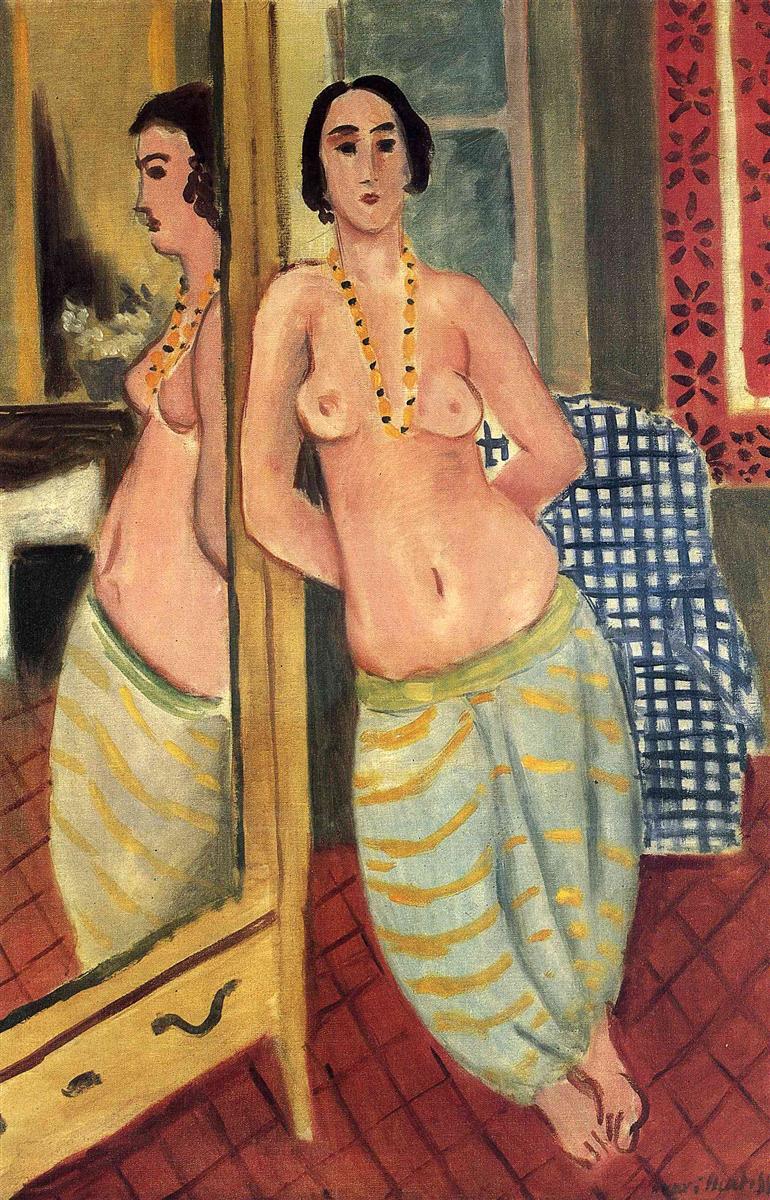

Henri Matisse’s “Standing Odalisque Reflected in a Mirror” (1923) is one of the most revealing statements from his Nice period, a decade in which the artist refined a serene, decorative modernism built from color harmonies, patterned interiors, and poised human presence. Here, a topless odalisque in billowing striped trousers leans against a tall dressing mirror. The model’s calm, frontal stance is doubled by her reflection, while the room’s red-tiled floor, patterned draperies, and blue-checked fabric create a chorus of motifs around her. The mirror does not introduce psychological drama so much as a compositional device that allows Matisse to show the body twice and to stage a conversation between real space and pictorial space. The canvas is an elegant study in balance: verticals against diagonals, warm reds against cool blues, satin flesh against matte pattern.

Historical Context and the Odalisque Theme

Matisse arrived in Nice in 1917 and, enchanted by its light, worked there for long stretches through the 1920s. The Nice pictures swap the explosive contrasts of Fauvism for a more measured radiance. The odalisque—a harem figure filtered through nineteenth-century Orientalism—became a studio fiction that justified the nude and invited a lavish decorative setting. Instead of storytelling, however, Matisse sought a new equilibrium where figure and décor possess equal dignity. In 1923, his idiom is confident: compressed space, simplified anatomy, ornamental planes that press forward like textiles, and interiors arranged as instruments of color. The mirror, favored in several works of the time, lets him double motifs and test the unity of his design.

Composition as Architecture

The composition is constructed around a tall, slightly angled mirror that divides the picture nearly in half. The model leans with one hip to the right of the frame; her reflected twin occupies the left. This hinge transforms the single figure into a diptych of poses that are almost—but not exactly—symmetrical: in reality her left arm is akimbo while in the reflection its angle shifts subtly as the wrist disappears behind the mirror’s frame. The mirror’s narrow base and visible drawer anchor the vertical, while the clay-red floor is drawn as a diagonal grid that slides under the figure and stabilizes the composition.

Matisse seeds counterweights around this central axis. A blue-and-white checked cloth draped over a chair at the right margin balances the warm red patterned textile at the far right. A pale, greenish window at the back adds a cool rectangle that quiets the heat of the floor and curtain. The odalisque’s striped trousers, rendered as pale blue punctuated by ocher dashes, echo the grid beneath her feet while adding a soft, undulating rhythm. The eye moves easily in a loop: mirror to face, necklace down to trousers, across the floor to the drawer’s curved handle, up the frame to the reflection, then back to the living figure.

Color Climate and Temperature Control

Color is the painting’s climate. The terracotta floor supplies a pervasive warmth that suffuses the lower half of the canvas. Against it, Matisse places cool zones: the gray-green window, the bluish trousers, and the blue-checked cloth. The odalisque’s skin—pearly creams tempered with faint violets—sits between these poles like a buffer, never chalky, always luminous. Small accents manage the temperature: the necklace of yellow and black beads sparks against the chest; the deep carmine of the lips anchors the face; the red panel with simple floral cutouts keeps the right side alive without overwhelming the figure. Nothing is arbitrary. Each hue contributes to equilibrium, allowing warmth and coolness to alternate like breaths.

Pattern and the Democracy of the Surface

The Nice period is often called “decorative,” a term Matisse embraced in its highest sense. Decoration here is not embellishment but structure. The tile grid gives the floor a slow beat; the checked fabric introduces a tighter rhythm; the red curtain’s cutout rosettes pulse in a contrary tempo. Even the trousers are striped with quick, ocher strokes that read as fabric and pattern at once. These motifs are not relegated to background. They share the same pictorial value as the figure. The mirror turns ornament into theme by repeating it: the red grid of the floor and the ocher dashes of the trousers are seen twice, proving that the painting’s order holds across both halves of the composition.

The Mirror as Device and Meaning

Mirrors in painting have long been vehicles for illusionism, voyeurism, or allegory. Matisse treats the mirror more like a compositional tool and a visual thought. It doubles forms, tests symmetries, and underscores the flatness of the surface. Notice how little depth the reflection adds: the odalisque’s mirrored body appears on the same plane as the real one; the frame is a thin band, not a deep portal. The mirror therefore does not open the room so much as fold it. By repeating the figure, Matisse can orchestrate two pink columns that stabilize the field of patterns, while the slight misalignments between body and reflection keep the image alive. The device also quietly emphasizes the act of looking. We see the model and we see an image of her; the painting becomes about appearances organized into harmony.

Drawing, Contour, and the Economy of the Figure

Matisse’s drawing is famously economical. The face is built from a handful of marks: an enclosing hairline, sloping brows, lids and pupils indicated with minimal darks, a short line for the nose, and a saturated mouth. The torso is described by contours that tighten and slacken with pressure, creating a living edge. The breasts are softly modeled with translucent shadows; the belly is a pale, cool plane. The hand set on the hip is simplified to an angular wedge that echoes the elbow’s notch. In the mirror, these decisions are repeated and slightly altered, reminding us that drawing here is less about anatomy than about rhythm—how a contour guides the eye from bead to shoulder to waist.

Light Without Theatrical Shadow

The room is evenly lit, as if bathed in warm, Mediterranean air. The flesh carries thin, cool shadows under the breasts and along the flank, but there is no heavy chiaroscuro. The mirror’s edge, a nimbus of creamy yellow, gathers this light and diffuses it. Because illumination is ambient, color carries most of the expressive load: the warm floor hums; the cool fabrics calm; the body glows between them. The absence of harsh cast shadows keeps the surface unified and maintains the feeling of calm.

Space Built by Layers, Not Perspective

Depth is realized by overlap and temperature rather than by strict vanishing points. The floor grid suggests recession but does not push us far back; the mirror’s base with its drawer opens a shallow alcove. The window becomes a cool rectangle rather than a deep view. The red curtain presses forward like a hanging textile. This layered space brings the viewer close—near enough to feel the scale of the beads, the angle of the hip, the cool touch of tile underfoot—and holds us inside the painting’s decorative order.

Costume, Jewelry, and the Grammar of Accents

The odalisque’s trousers and necklace are not props so much as punctuation. The striped fabric breaks the long sweep of the body with a supple bass line of blue-gray and ocher notes, while the necklace adds a staccato of bright beads that focus the chest and establish a color dialogue with the red tiles and curtain. Their reflection in the mirror confirms their structural role: they appear as twin phrases in the painting’s musical sentence, binding the two halves of the design.

Gesture, Gaze, and the Tone of Presence

The model leans with one leg crossed and the hip cocked, an alert, unforced pose that suggests a pause rather than a performance. Her left hand sets on the waist in a compact triangle; the right arm drops behind the mirror’s frame. The gaze is steady, neither coy nor confrontational. Matisse prefers composure to drama; he paints presence—the simple fact of a person convening color and pattern around her. The mirror intensifies this presence by insisting that the figure is the organizing principle of the room twice over.

Orientalism Reframed

As with other Nice-period odalisques, the subject carries the long history of Orientalism, a European fantasy space that sanctioned the nude through a distant cultural frame. Matisse borrows elements—trousers, patterned textiles, a theatrical setting—but empties them of narrative. The odalisque is not a character in a story; she is a modern body participating in a pictorial harmony. The mirror’s doubling underlines this: what matters is not the exotic myth but the formal relations that make the painting sing.

Brushwork and the Trace of Making

The surface retains a tactile record of the artist’s hand. The tile lines are drawn quickly, repeating with small deviations that keep the floor from dead regularity. The trousers’ ocher dashes are laid in with loaded, elastic strokes. The red curtain is stamped with simple leaf shapes applied in a steady rhythm. On the body, paint thins in places so the ground peeks through, letting the skin breathe. The mirror’s frame is pulled with a single confident stroke whose edges feather into the surrounding color. These touches give the canvas its liveliness; we sense deliberation without fussiness.

Rhythm and the Music of Looking

Repeated motifs—grid, checks, stripes, beads—establish a beat that carries the eye. The mirror doubles this beat, like a musical echo. Between beats, Matisse leaves rests: the soft plane of the abdomen, the cool rectangle of the window, the pale field between necklace and navel. The tempo is unhurried, the kind of time one spends while dressing, daydreaming, or meeting one’s reflection. The painting asks us to look with that same steady tempo.

Comparisons Within 1923

Compared with “Moorish Woman with Upheld Arms,” where the figure fills the frame and sits on a striped chair, this work is more architectural. The floor grid, mirror frame, and window panes make a scaffolding against which the soft body and fabrics play. Compared with standing odalisques against pink walls, it is more intimate: the viewer stands almost on the tiles, an arm’s length from the model. Across these canvases, however, the logic remains consistent—figure as central chord, ornament as counterpoint, color as light, and space as layered fabric rather than deep stage.

How to Look: A Slow Circuit

Begin at the necklace—bead, gap, bead—and feel the rhythm. Drop to the ocher dashes of the trousers; let them lead you onto the terracotta grid. Travel left to the mirror’s base and up its pale edge; meet the reflection’s mouth, then eyes, then hair. Cross the seam to the living face and return to the blue checks at the right margin; notice how they cool the hot floor. Slide up the red curtain’s leaf shapes and back to the necklace where you began. Each loop reveals new harmonies: the echo between grid and stripe, the dialogue between blue and red, the way the mirror flattens space even as it doubles it.

Material Presence and Human Scale

Despite the decorative richness, the painting feels touchable. You can imagine the weight of the beads, the coolness of the tiles, the slight wobble in a hand-painted pattern, the smooth varnish of the mirror’s frame. This human scale—the sense that everything was arranged and painted in a real room—grounds the work’s elegance in lived experience. It is not a sterile design but a vivid moment formalized.

Conclusion

“Standing Odalisque Reflected in a Mirror” crystallizes the Nice period’s poise. Matisse turns a familiar studio motif into a lesson in pictorial balance: the body is calm and central; the mirror doubles and tests the design; pattern becomes architecture; color carries light; space is layered rather than deep. The result is not a narrative scene but a state—a lucid, decorative harmony where looking itself is the subject. Nearly a century later, the painting still breathes with that clarity. It invites us to stand on the red tiles, share the mild air, and watch as a person and her reflection hold an entire room in equilibrium.