Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

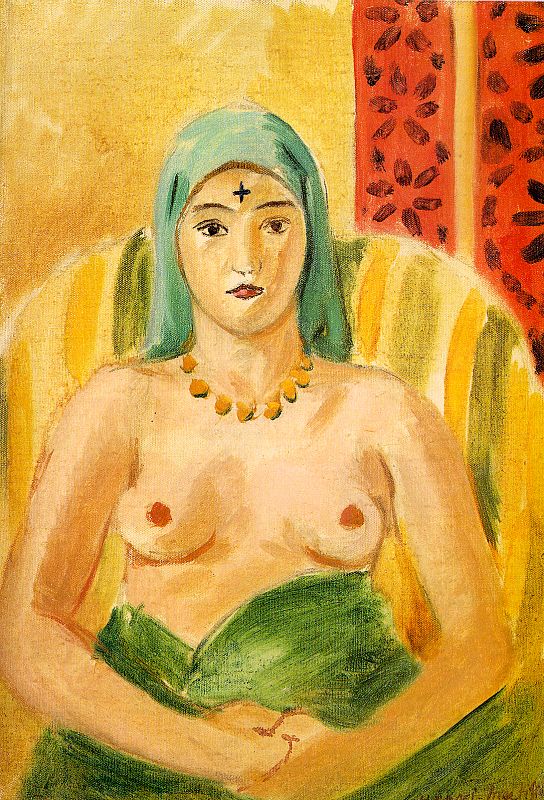

Henri Matisse’s “Odalisque, Half-Length (The Tattoo)” (1923) distills the Nice period into a single, frontal encounter: a half-length odalisque seated close to the picture plane, her torso bare, a green wrap gathered at the waist, a turquoise headscarf framing the face, and a tiny black tattoo or talismanic mark centered on her forehead. She sits before a striped yellow-green armchair and a soft, sun-soaked wall while a crimson drape patterned with leaf forms rises at the right margin. The composition is simple, almost iconic, yet it carries the full grammar of Matisse’s decorative modernism—calibrated color, rhythmic pattern, an economy of drawing, and a spatial compression that makes the viewer share the model’s air. Within this intimate format, Matisse turns the charged Orientalist motif of the odalisque into a serene study of presence and harmony.

Historical Context and the Nice Vocabulary

By 1923 Matisse had spent several years working in Nice, where the even Mediterranean light allowed him to paint from the model in interiors perfumed by textiles, screens, flowers, and patterned furniture. During this phase he refined a language distinct from the raw dissonances of Fauvism: luminous but moderated color, flattened space organized by ornamental planes, and figures treated as calm centers within decorative climates. The odalisque served as a studio fiction that legitimized the nude and opened the door to saturated color and lavish patterns; yet Matisse stripped the theme of narrative intrigue. In place of theatrical scenes, he pursued clarity—figures at rest, décor pressed forward like textiles, and a mood of cultivated poise. “Odalisque, Half-Length (The Tattoo)” compresses that vocabulary to devotional scale: no table, carpet, mandolin, or window—only a woman, her ornaments, and three interlocking fields of color.

Composition as Icon

The composition reads like a modern icon. The sitter is centered, cropped just below the waist, and held in a shallow arc of the upholstered chair whose yellow-green stripes rise behind her like a halo of vegetal light. The shoulders and upper arms establish a broad horizontal that stabilizes the rectangle; the green wrap slants upward in a diagonal that gathers the torso. The face sits squarely above the sternum, turning the body into a vertical axis. At the right edge, a narrow red panel patterned with dark leaf shapes punctuates the background, counterbalancing the warmer wall and preventing the composition from floating. The viewer’s eye loops along a clear circuit—tattoo at the forehead, eyes and lips, necklace, edges of the breasts, fold of the wrap—and then returns to the calm triangle of the headscarf. The arrangement is frontal yet tender, ceremonial without stiffness.

Color Climate and Temperature Control

Color acts as the painting’s atmosphere and structure. The ground is a warm, honeyed yellow that suffuses the room with daylight; the chair’s vertical bands of lemon, olive, and pale cream lift behind the figure like stylized foliage; the right drape is a saturated red whose repeating leaf forms supply a cool maroon counter-rhythm. Against this warm envelope, the turquoise headscarf brings a cooling breeze that freshens the complexion and sets the flesh into gentle relief. The green wrap across the lower torso answers the headscarf chromatically, tying top and bottom in a single cool arc. Flesh is modeled with soft apricots and pearly grays; shadows remain transparent, never heavy, so that the skin breathes. Small accents modulate the temperature: the vivid coral of the lips, the tiny black of the tattoo, and the ocher beads of the necklace. Nothing jars; each hue is a tuned note in a chord of quiet intensity.

The Tattoo, Headdress, and Necklace as Pictorial Anchors

Matisse punctuates the face with a single dark sign at the forehead—readable as a tattoo, talisman, or mark of exoticism borrowed from Orientalist vocabulary. Formally, this dot-cross is a keystone: it gathers the arcs of the brows and the headscarf’s curve, fixes the viewer’s first glance, and then releases it down the vertical of the nose to the red of the lips. The turquoise scarf, painted in broad, pliant strokes, frames the visage with cool light and turns the head into a self-contained pavilion. The necklace of round yellow beads repeats the headscarf’s semicircle at a lower register; bead by bead, it breaks the long plane of the chest with a staccato rhythm and catches warm reflections from the wall. These three ornaments—mark, scarf, necklace—compose a hierarchy of accents that organize the entire field.

Drawing and the Economy of the Figure

Matisse’s line is spare and exact. The face is constructed with a handful of strokes: a continuous contour for the hairline and scarf, simplified eyebrows, brief lids with small darks for the pupils, and a short, weighted line for the philtrum. The nose is a succinct planar indication; the lips are a single saturated shape that anchors the visage. The breasts are treated without melodrama—gentle circles with cool shadows beneath, their modeling subordinate to the overall surface. The arms and hands are reduced to essential contours; the right hand rests at the lap as a pale, triangular fold half-hidden by the wrap. This economy lets the painting keep the freshness of a first, confident statement while leaving room for color to carry emotion.

Pattern, Ornament, and the Democracy of Surfaces

What distinguishes the Nice interiors—and this half-length variant—is the equal dignity accorded to figure and décor. The armchair’s stripes do not vanish behind the body; they press up to the same pictorial level, like ribbons of light. The red drape’s leaf motifs echo the beaded necklace and the chair’s vegetal overtones, creating a web of rhymes. Ornament is not added trim; it is the painting’s syntax. Repetition establishes tempo; contrast articulates edges; simplified motifs keep the surface legible. The result is a democratic image where flesh, fabric, and wall belong to one order of value: colored shapes held in poised relation.

Light, Flesh, and the Refusal of Hard Shadow

Light in the painting is ambient, as if the room were filled with warm air rather than pierced by a single beam. Shadows remain open and transparent—cool violets at the neck hollow, olive notes along the ribs, a soft slate beneath the breasts. Because Matisse refuses heavy chiaroscuro, the figure does not thrust forward theatrically; instead, it resides in the same luminous plane as the décor. This approach allows color to shoulder the expressive load. Warm ground, cool scarf, red panel, green wrap, and pearly skin cooperate to create mood without resorting to deep illusion.

Space by Layering Rather Than Perspective

The interior is shallow but believable. The striped chair provides a close, gently curving field; the wall presses forward as a textured plane; the red drape slides in from the edge like a decorative bookmark. Overlaps, not vanishing points, do the work of spatial description. The compression not only enhances intimacy but also amplifies the painting’s icon-like character: we face the sitter at conversational distance, neither distanced by perspective nor distracted by elaborate props.

Gesture, Psychology, and the Ethics of Poise

The odalisque’s posture is restful and centered. She sits upright, hands loosely joined at the wrap, shoulders relaxed, gaze steady but unaggressive. The mark on the forehead introduces a touch of mystery without tipping into theater. Rather than narrative psychology, the painting offers a state of being—self-possessed calm—mirrored by the décor’s quiet rhythms. This is the Nice period’s ethical tone: pleasure without spectacle, intimacy without intrusion, composure without coldness.

Orientalism Reframed

The title identifies the sitter as an odalisque and attends to the “tattoo,” signaling the Orientalist scaffolding inherited from nineteenth-century art. Matisse borrows elements associated with that tradition—headscarf, jewelry, patterned textiles—but empties them of story and voyeuristic drama. The figure becomes a modern icon of presence within an ornamental climate, not a character in a colonial tableau. The tattoo functions less as ethnographic marker than as a pictorial tool: a tiny fixed star around which the composition rotates.

Material Presence and the Touch of the Brush

The painting’s intimacy also resides in its surface. The warm wall is a thinly scumbled field through which the weave of the canvas flickers. In the headscarf, wetter, more elastic strokes register the brush’s curve and lift at the ends; their edges breathe, allowing the ground to glow through. In the green wrap, strokes accumulate in small, directional bands that suggest weight and gather light along the fold. The red drape is tamped in with confident, repeated leaf marks. Each zone carries a different tempo of touch, and the transitions between them—wall to chair, chair to flesh, flesh to fabric—are managed with soft edges that keep the whole surface continuous.

Rhythm and the Music of Looking

Visual rhythm organizes the viewer’s journey. The beaded necklace enacts a small, repeated beat across the chest; the chair’s stripes run in longer measures up the background; the red drape’s leaf shapes sound a counter-pattern; the tattoo is a single decisive downbeat at the top of the measure. Between these beats, Matisse leaves rests: the clear plane of the chest, the even field of the wall, the quiet triangle of the wrap. The eye moves with ease, never snagging on gratuitous detail, sustained by a tempo of repose.

Comparisons Within 1923

Compared with Matisse’s larger, more elaborate odalisques of the same year—figures reclining on striped couches, surrounded by tambourines, screens, and plants—this half-length version is austere. Its power lies in concentration. The same color climate recurs—lemon and olive, coral and turquoise, warm ground and cool accents—but the stage has been simplified to a chair and a strip of drapery. That restraint throws the face, the tattoo, and the headscarf into relief and clarifies the painter’s primary interest: how a figure can be set in equilibrium with a pared-down decorative field.

How to Look, Slowly

Begin at the small tattoo and feel how it anchors the face; descend to the eyes and allow the red of the lips to hold your gaze for a breath. Step outward to the yellow beads and count them like a quiet rosary. Let your eye slip along the round edges of the breasts, then down to the green wrap where cooler notes pool in the folds. Sweep back up through the chair’s striped halo; pause at the red drape and watch its leaf forms rhyme with the necklace and with the chair’s vegetal mood. Each circuit reveals the painting’s calm logic: small accents governing broader fields; cools steadying warms; ornament serving presence.

Conclusion

“Odalisque, Half-Length (The Tattoo)” offers the Nice period in miniature: a human presence tuned to an ornamental climate, color bearing the weight of emotion, drawing pared to essentials, and space compressed to intimate nearness. The odalisque motif supplies the pretext; Matisse’s true subject is balance. Within a few planes—warm wall, striped chair, red drape—and a handful of accents—tattoo, scarf, necklace—he composes a serene icon of modern beauty. The painting does not ask for narrative; it asks for attention, and rewards it with an equilibrium that feels inevitable and humane.