Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

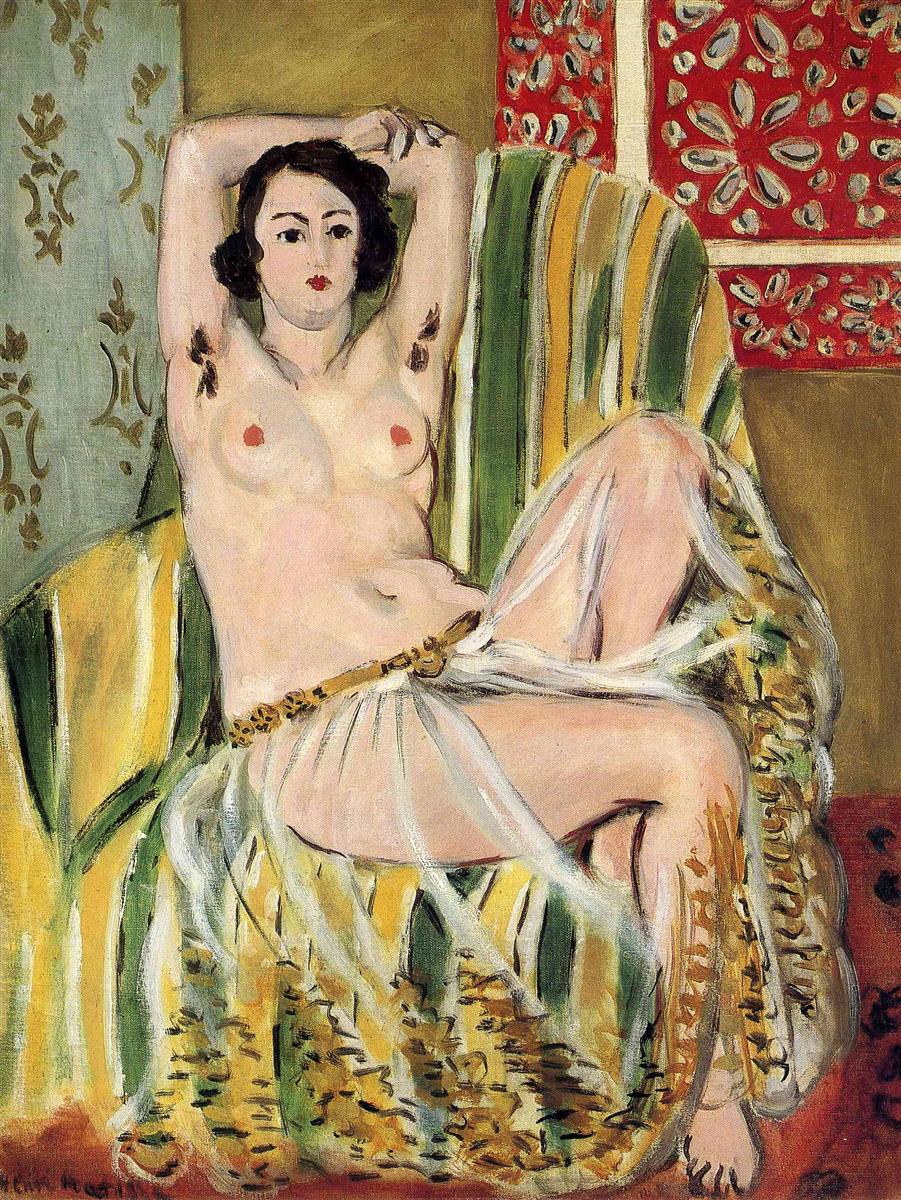

Henri Matisse’s “Moorish Woman with Upheld Arms” (1923) belongs to the luminous core of his Nice period, when the artist transformed interiors into stages for color, ornament, and poise. A nude model reclines on a striped, yellow-green armchair, her arms raised behind her head in a relaxed yet arresting gesture. Around her, patterned walls—olive arabesques at left and a red screen with floral cutouts at right—press forward like textiles. A gauzy, gold-trimmed sash loops around her hips, falling in translucent ribbons that mingle with the chair’s fringed covering. The painting appears effortless, but it is built with rigorous orchestration: the body’s geometry answers the architecture of the décor, and each color inhabits a precise role in the larger harmony.

Historical Context and the Nice Period

After 1917, Matisse spent extended stretches in Nice, seduced by its steady light and the ability to work with models in rooms filled with fabrics, screens, carpets, and plants. This phase did not abandon the bold chroma of Fauvism; it redirected it toward serenity. He turned from shock to equilibrium, from dramatic disjunctions to finely tuned consonances. The odalisque motif—descended from Ingres and Delacroix—offered a pretext for the nude while legitimizing an interior world saturated with pattern. “Moorish Woman with Upheld Arms” stands at the middle of this project. The odalisque becomes less a narrative figure than a formal instrument through which Matisse composes color and line into calm radiance.

Composition and the Architecture of the Pose

The body forms a dynamic triangle, its apex at the clasped hands above the head and its base along the spread of thighs and the chair’s cushion. The left knee lifts to create a counter-rhythm against the lean of the torso, while the right leg extends toward the lower edge, anchoring the composition. The arms, arcing gently behind the head, turn the upper body into a caryatid, a vertical support that holds the surrounding décor in balance. The chair’s stripes rise diagonally and then curve around the figure like a drapery; they are not passive upholstery but directional vectors that amplify the pose. The eye travels a circuit—hands, face, breasts, sash, knee, foot, back to the lifted arms—without ever leaving the painting’s warm climate.

Color Climate and Temperature Control

Color here is atmosphere. Honeyed yellows and olive greens dominate the armchair and foreground, producing a mellow heat. Against this, Matisse sets cool, pearly flesh modeled with soft grays and faint violets; the skin feels luminous rather than sculpted. The red panel at right, punctured by pale floral shapes, raises the temperature and supplies a necessary keynote of saturation. On the left, a dusty chartreuse wall printed with subdued motifs keeps the composition from splitting into two hot halves. Small accents—crimson lips, the tiny black wedge of the pubic triangle, chocolate shadows in armpits and hair, the golden links of the hip ornament—operate like tuning pegs, calibrating intensity so that no area overwhelms the whole.

Ornament, Pattern, and the Democracy of the Surface

Matisse’s modernism is decorative in the high sense: every part of the picture carries equal dignity. The red Moorish screen, with its stenciled rosettes and borders, and the pale wall with olive sprays do not retreat behind the figure; they press forward into the same visual plane. The fringed throw beneath the model turns into a field of small, leaf-like marks, echoing the wall’s motifs. The transparent sash, striped by the chair’s color where it overlaps, demonstrates how ornament can be both a pattern and a material effect. Decoration becomes a thinking tool—its repetitions establish rhythm, its contrasts articulate space, and its motifs rhyme with the body’s curves.

Drawing, Contour, and the Economy of Means

Matisse’s draughtsmanship is spare and assured. The face is built from a handful of strokes: a continuous outline for the hair, a neatly weighted nose bridge, arched brows, succinct lids, and lips carrying a saturated accent. The breasts are described with minimal modeling—lightly touched circles that avoid gravity and drama. The lifted arms are elegant arcs, their edges elastic rather than hard. Along the thighs, a single firm contour carries much of the descriptive load. Everywhere, the line is allowed to breathe, to open and close in pressure, so that the figure remains vivid without overdefinition. This economy preserves freshness and integrates the body seamlessly with the décor.

Light, Flesh, and the Refusal of Illusion

Light in the Nice paintings is ambient and generous. There is no theatrical spotlight; the body glows as if lit by the room itself. Shadows are cool violets, slate grays, and olive notes that remain within the chromatic harmony. They suggest volume without threatening the painting’s essential flatness. The result is a paradox: palpable flesh sustained by a surface that refuses deep illusion. Matisse convinces not by mimicking three-dimensional reality but by keeping the entire field alive with interrelated tones.

Space as Layered Planes

The room is shallow, constructed by layering rather than by perspective. The red screen sits close behind the figure, its cream bands acting like posts; the patterned olive wall on the left presses forward to meet the chair’s back; the floor is scarcely differentiated from the lower fringe of the throw. Overlaps, not vanishing points, articulate nearness and distance. This compression enhances intimacy. The viewer is brought into the same air as the model, and the optical pleasure of color relationships replaces the drama of depth.

The Sash, Jewelry, and the Grammar of Accents

The translucent sash threaded with gold at the hips does more than cover; it is a structural hinge. Where it crosses the chair’s stripes, it becomes a veil that reveals the underlying color, a painterly demonstration of transparency. The small chain clamped at the waist punctuates the long lines of the torso with a staccato of glints. These details, modest in scale, carry outsized compositional weight. They tether the eye at the center before allowing it to glide again along the broader rhythms of limb and chair.

Gesture, Gaze, and the Tone of Presence

The odalisque reclines with an air of unstudied sovereignty. Her raised arms expose the torso without strain; the left knee lifts as if by habit; the gaze meets ours not coquettishly but with level attention. Matisse avoids melodrama. The psychological tone is one of poised availability—present, at ease, and undisturbed by the act of looking. This quiet confidence is fundamental to the Nice period’s ethic of pleasure: the body is celebrated not as spectacle but as a participant in a larger harmony.

Orientalism Reframed

The title names a “Moorish woman,” signaling the Orientalist lineage that allowed European painters to stage nudes within an imagined harem. Matisse borrows the decorative vocabulary—screen patterns, sash, hints of exotic textiles—but he drains the subject of narrative. The figure is not pinned to ethnographic identity; she is a modern body set among harmonies. By foregrounding pattern and color rather than anecdote, the painting shifts attention from fantasy to form. While the motif’s history cannot be erased, here it becomes a scaffold for investigating how the human figure can live inside an ornamental world without being diminished by it.

The Chair as Modern Throne

The armchair, with its thick stripes of olive, lemon, and cream, functions like a throne for ordinary life. Its rounded back echoes the curve of shoulders and the swoop of lifted arms; its seat, draped in a fringed throw, provides a luscious field against which skin reads with heightened clarity. The stripes act as directional energy, rising behind the model and sweeping down beneath her, binding figure to furniture. Matisse often granted everyday objects ceremonial roles; here, the chair’s monumental presence confers dignity without pomp.

Brushwork and the Trace of Making

The painting’s vitality resides in the variety of touches. In the throw, short dabbed notes and dragged strokes mimic the rough shimmer of fringe. Along the armchair’s stripes, broader sweeps bend with the chair’s curvature, sometimes leaving a bare edge of canvas that sparkles like light on fabric. The screen’s motifs are tamped into place with quick, confident marks; the wall’s olive sprays are swept in with a flexible wrist, letting bristles record their own rhythm. On the flesh, paint thins and thickens with delicate control. These traces of process keep the image breathing; the surface reads as the record of a conversation between eye, hand, and motif.

Rhythm, Interval, and the Music of the Interior

Matisse composes like a musician. The repeated elements—the screen’s rosettes, the wall’s sprays, the chair’s stripes, the fringe’s flutter—establish a beat that carries the gaze in slow measures around the canvas. Between these beats, he leaves intervals of quiet: the soft plane of the abdomen, the open field of the forearm, the calm oval of the shoulder. The result is a tempo of repose—neither static nor hurried—perfectly matched to the model’s unforced pose.

Comparisons Within the 1923 Group

When placed beside other Nice-period works from the same year—standing odalisques against pink walls, seated readers in yellow blouses—this painting is both more intimate and more theatrical. Intimate, because space is compressed and the body fills the frame. Theatrical, because the red screen and high-contrast stripes intensify the sense of staging. Yet the structural logic is shared across the series: a central body stabilized by ornament, warm fields balanced by cool flesh, and a refusal of deep perspective in favor of layered planes. “Moorish Woman with Upheld Arms” shows Matisse’s language at full fluency.

Material Presence and Human Scale

Despite the decorative splendor, nothing feels remote. The scale remains human, the touch legible. The chair’s weave and fringe invite tactile memory; the sash’s transparency is as persuasive as a held piece of gauze; the screen’s cutouts read as painted wood you could tap with a knuckle. This material presence is crucial to the painting’s hospitality. It offers not the icy perfection of polished surfaces but the warmth of things made by hand and used in rooms where people sit, stretch, and breathe.

How to Look, Slowly

Begin at the clasped hands above the head and trace the elegant S down the right arm, across the breast, and into the sash. Let your gaze jump to the lifted knee, then slip along the fringe toward the lower edge. Rise with the chair’s stripes to the left shoulder and back to the face, noticing how a few dark notes locate eyes and hair with finality. Cross into the red screen and feel its saturated throb before cooling your eyes on the olive wall. Repeat this circuit until the painting’s climate—its alternation of hot and cool, patterned and plain—settles into a single, steady breath.

Conclusion

“Moorish Woman with Upheld Arms” crystallizes Matisse’s belief that beauty is a function of equilibrium. A relaxed body, a ceremonial chair, patterned walls, and a handful of disciplined accents are tuned so precisely that they achieve a calm intensity. The image is not a story but a state: poised pleasure. It demonstrates how the figure can be honored by décor rather than smothered by it, how color can carry emotion without sentiment, and how painting can create a room where the eye rests and rejoices at once. In 1923, Matisse could make a harmony so assured that it feels inevitable. The canvas still breathes with that assurance.