Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

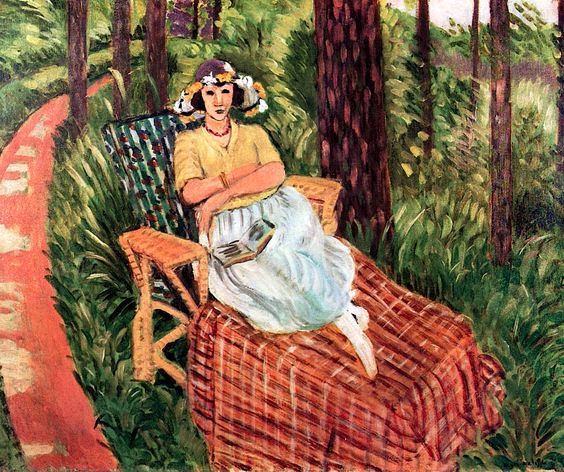

Henri Matisse’s “Repose Among the Trees” (1923) captures an oasis of calm in the open air, where a seated woman settles into a wicker armchair set on a plaid blanket while summer grasses surge around her like a green tide. A red path curves through the background and vanishes among slim tree trunks, and the sitter—crowned with a floral garland, bracelets glinting at the wrist—rests with arms loosely crossed and a small book slipping against her skirt. Painted during Matisse’s Nice period, the scene extends the serenity of his interiors into nature, preserving his hallmarks—decorative rhythm, compressed space, and a preference for luminous color—while exchanging patterned wallpaper for the ornamental abundance of a wood. What looks like leisure is, in fact, a finely tuned orchestration of line, color, and interval that invites the eye to linger and breathe.

Historical Context and the Nice Period Outdoors

Matisse’s years in Nice, beginning in 1917, are best known for interior odalisques and seated figures framed by screens and carpets. Yet he often carried this language outdoors, using gardens, terraces, and groves as stages for the same exploration of poise and harmony. “Repose Among the Trees” belongs to this open-air subset. Instead of tiled panels or brocade curtains, the supporting décor is provided by pine trunks, tufted grasses, and a meandering path whose warm brick color answers the reds he loved inside. The figure is neither working nor posing theatrically; she is resting with alert composure, a quality Matisse prized because it mirrored his own working method: sustained attention without strain, intimacy without sentimentality.

Composition and the Architecture of Rest

The composition is anchored by a stable pyramid formed by blanket, chair, and skirt. The plaid blanket, spread diagonally across the foreground, establishes a firm base whose crossing bands serve as a quiet grid. Above this base, the wicker chair wings out to left and right, framing the sitter and imparting a gentle monumentality to an otherwise domestic object. The sitter’s angled forearms create a small triangle within the larger one, focusing attention at the center without tightening the pose. Behind the figure, two tree trunks rise like slender columns, and between them the green understory ripples with small strokes. At far left the path curves into the picture with a confident sweep, setting a counter-diagonal that prevents the pyramidal structure from becoming static. Matisse’s placement lets the scene feel both composed and unforced—the geometry is there, but it breathes.

Color Climate and the Dialogue of Warm and Cool

Color carries the painting’s mood before any details register. A generous spectrum of greens—olive, sap, viridian, and spring—dominates the middle and background, shifting temperature as grasses catch light or fall into shade. Against this cool, living field, Matisse lays warm accents: the terra-cotta red of the path, the honey tones of the wicker, a salmon-pink necklace and bracelet, and the russet and cream bands of the blanket. The sitter’s blouse is a soft, sun-warmed yellow that binds warm and cool together, while the pale blue skirt introduces a cooling note that keeps the center from overheating. These exchanges of temperature do more than delight the eye; they mark transitions in space and material, guiding attention from flesh to fabric to ground in a cadence that feels natural and calm.

Pattern, Ornament, and the Garden as Textile

Although the scene is outdoors, Matisse treats it with the same decorative intelligence he brought to interiors. The blanket’s plaid is the most explicit pattern, its perpendicular bands acting like a miniature floor plan that stabilizes the foreground. The wicker’s woven diagonals repeat and soften that geometry, while the floral garland in the sitter’s hair offers a small, bright wreath of repeated shapes. Most important is the vegetation itself. Rather than detailed botany, the grasses are simplified into strokes and clusters that read as an all-over pattern, a green brocade draped across the ground. The trees, with bark suggested in vertical streaks, become tall stripes. In this way, Matisse translates nature into textiles without diminishing its vitality. The grove is a living wallpaper that sings behind the figure.

The Red Path and the Logic of Movement

The curving path at left provides the composition’s principal movement. Entering from the lower corner and sweeping toward the horizon, it carries the eye into depth while remaining decoratively flat, its edge defined by a light border that reads like a stitched hem. The path’s color—between brick and rose—replies to the warm accents of jewelry and blanket, knitting the picture’s edges to its heart. In a painting about rest, the path offers the promise of motion that is not taken. It suggests time outside the frame—walks taken earlier or to come—while the present is dedicated to stillness. This dialectic between movement and repose keeps the image alive.

The Figure’s Pose and the Psychology of Ease

The sitter is self-possessed rather than languid. Her arms cross loosely, hands tucked without tension, shoulders aligned with the chair’s broad arms. The head, crowned with flowers, tilts just enough to suggest thoughtfulness. The small book nestled at the lap hints at a pause in reading rather than abandonment; its oblique angle creates a delicate hinge between the triangle of forearms and the larger triangle of skirt and blanket. The expression is calm, reserved, and open. Matisse avoids the heavy psychology of narrative portraiture; he aims instead at a state of being—alert rest—that matches the gentle hum of summer around her.

Drawing, Contour, and the Economy of Description

Matisse’s drawing is as spare as it is decisive. The jawline is a single confident curve; the eyes are indicated with minimal strokes; the nose is a brief plane; the mouth carries just enough saturation to anchor the face. The arms are described by outer contours and a few temperature shifts that suggest volume without fuss. The wicker chair’s angles are abbreviated into assertive diagonals; its woven texture is suggested, not itemized. The grasses are a calligraphy of flicks, each registering direction and growth without explaining every blade. This economy is crucial to the painting’s freshness: the fewest possible marks deliver the greatest clarity.

Light, Surface, and the Refusal of Heavy Shadow

Light in “Repose Among the Trees” is ambient and gentle, as if filtered through a thin canopy. Matisse models form with temperature more than with value, using cooler greens and blues to suggest shadow and warmer yellows and ochers for sunstruck areas. There are no theatrical cast shadows to pin the figure to the ground; instead, subtle darks gather where skirt folds overlap or where the arm meets the torso. This restraint preserves the painting’s calm and prevents hard contrasts from interrupting the overall rhythm. The surface itself alternates thin scumbles—especially in the grasses—with richer, more buttery strokes in the blanket and chair, allowing the ground’s weave to sparkle in places and lie smooth in others.

Space by Layers Rather Than Perspective

The space of the painting is shallow but believable, built from stacked bands rather than from deep linear recession. Foreground is defined by the plaid blanket’s close scale; middle ground by the chair, figure, and dense grasses; background by the vertical trunks and the path’s bend. The path delivers the single strong cue to depth, but even it is treated like a ribbon laid over the field. The trees are vertical markers that press the background forward rather than tunneling it away. This layered construction keeps viewer and subject in intimate proximity, as if we were standing at the edge of the blanket, sharing the same summer air.

The Book, Leisure, and Modern Time

The small book is a modern emblem of time spent intentionally. In Nice-period interiors, reading often anchors Matisse’s images of cultivated leisure. Bringing the book outdoors relocates that attentive silence to a grove, where text meets rustling leaves. The moment depicted is not dramatic: it is the in-between time when the reader pauses, perhaps mid-sentence, to let words settle. The arm across the book and the floral crown together balance thought and sensation—mind held by language, senses bathed in chlorophyll. The painting’s ethos is not escapism; it is a proposal that repose is a meaningful, even necessary, modern act.

The Wicker Chair as Modern Throne

Matisse often grants ordinary furniture a touch of ceremony. The wicker armchair—with splayed legs and broad arms—functions here as a modern throne, conferring dignity without pomp. Its honey hues warm the center, its diagonals enliven the rectangle, and its surface catches highlights that spark against the cooler greens. Because wicker is made of interlaced strands, it echoes the painting’s own woven logic: color bands crossing, brushstrokes interlacing, patterns overlaying. The sitter’s garland and jewelry add small regalia, completing the gentle coronation of everyday rest.

The Blanket and the Pleasure of Touch

The plaid blanket, with its russet and cream checks, is the most tactile passage in the picture. Its diagonal orientation leads the viewer in and provides a cushioned stage for the chair. Matisse renders the fabric’s weight with broader, oil-rich strokes, letting the color mingle wet-in-wet so the checks blur at their edges, just as woven threads do. This handling contrasts with the quicker, grasslike touches in the ground, intensifying the sensation of softness against the textured, vertical world of trunks and blades. The blanket becomes a touchstone for the whole composition—human comfort set against nature’s upward surge.

Rhythm and the Sound of a Summer Grove

Although silent, the painting is rhythmic. The tree trunks knock out a slow, vertical beat; the path adds a long, curving phrase; the grasses ripple in small, syncopated strokes; the plaid’s grid hums beneath it all like a steady drone. The sitter’s crossed arms and angled forearm over the book sound a gentle cadence at the center. This musicality is characteristic of Matisse: he composes not only with hue and value but with the tempo of shapes and marks. The grove becomes a score, and the figure, resting yet alert, is its sustained note.

Relationship to Other Works of 1923

Placed alongside Matisse’s 1923 interiors—odalisques in patterned rooms, women in yellow reading or holding music—“Repose Among the Trees” exchanges enclosed décor for a living one. Yet the structural logic remains the same: a central figure stabilized by patterned planes, warm accents balancing cool fields, shallow, layered space replacing deep perspective. The floral crown recalls studio flowers translated into wearable color; the book connects to the theme of cultivated leisure; the red path stands in for the red carpets that often organize his rooms. The painting thus demonstrates how portable Matisse’s pictorial system is—capable of harmonizing a grove as effortlessly as a salon.

Emotion, Ethics, and the Quiet Radicalism of Calm

The painting’s feeling is neither sentimental nor aloof. It proposes an ethic of calm: that rest, attention, and beauty arranged with care are valuable in themselves. In a century of speed and fracture, Matisse’s insistence on equilibrium is quietly radical. The sitter’s poise, the measured color, and the considered intervals of the composition combine to offer a model of humane order. Pleasure here is not excess; it is proportion. Nature is not a sublime force to dwarf the figure; it is a companion that sings at the same volume.

Material Presence and the Trace of Making

Standing before the canvas, one would see how the painting’s life depends on the variety of touches. In the grasses, the brush often travels in swift, lightly loaded runs, leaving the ground visible and letting light percolate. In the blanket and chair, paint is thicker, spreading with the drag and lift that record the hand’s pressure. In the face and blouse, strokes are more compressed and fused, giving stability to the center. The floral crown is a series of small, loaded dabs—yellows, whites, and lavenders—placed with just enough separation to twinkle. These traces of process are not incidental; they are the painting’s pulse.

How to Look: A Slow Circuit Through the Grove

Begin at the red path’s lower curve and let your gaze travel upward until it vanishes among trees. Slide across the grasses to the wicker’s honey light and rest at the sitter’s hands where book and forearm meet. Rise to the face and garland, then drift outward to the vertical trunks, feeling their rhythm. Drop to the blanket’s diagonal checks and follow them back to the path’s edge. Each loop through this circuit reveals new harmonies: the way the blanket’s warm reds answer the path, the way the skirt’s cool blue calms the surrounding green, the way the garland’s small blossoms repeat the dabs that describe distant leaves. The painting rewards this slow looking; its peace grows with time.

Conclusion

“Repose Among the Trees” extends Matisse’s Nice-period ideals into the open air, proving that his decorative modernism is not confined to walls and carpets. Here, the grove itself becomes ornament, the path a ribboning arabesque, and the wicker chair a throne of light. The figure’s calm, the gentle climate of color, and the measured complexity of the composition create a durable image of humane leisure. It is not an escape from the world but a vision of how to dwell in it—attentive, balanced, and at ease.