Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

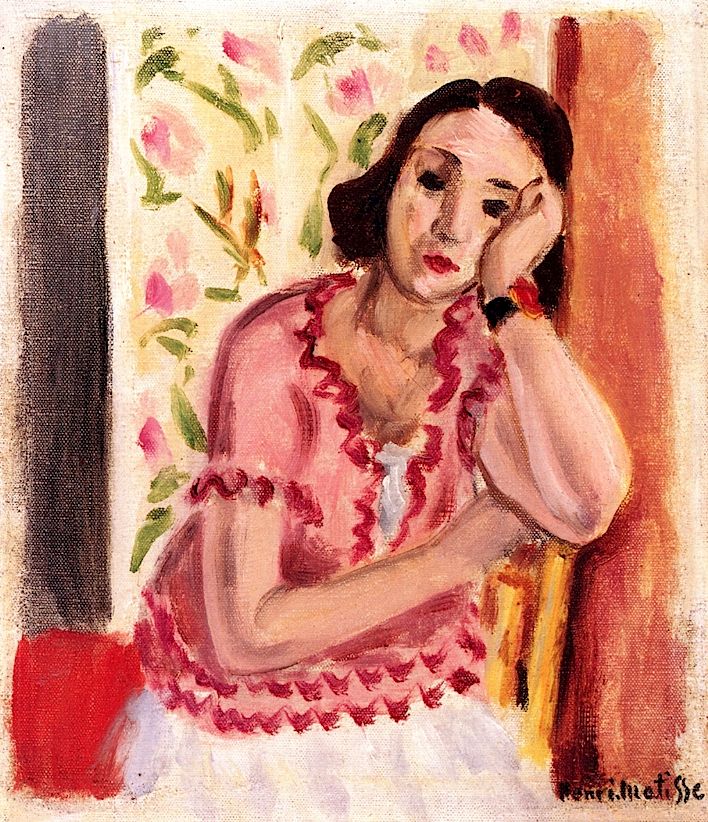

Henri Matisse’s “Woman Leaning” (1923) is a small but resonant canvas from his Nice period, a decade defined by domestic interiors, patterned backdrops, and a tender attention to human presence. The painting shows a woman seated in profile, elbow on the table or chair arm, cheek pressed lightly into her hand. She wears a pink blouse trimmed with playful ruffles, and behind her unfurls a pale wall scattered with floral marks. The entire scene feels intimate and unhurried, as if the room itself were breathing. In this picture, Matisse transforms a seemingly casual posture into an orchestration of color, line, and mood that conveys the quiet intensity of everyday life.

Historical Context

By the early 1920s Matisse had settled into a rhythm in Nice that allowed him to work daily with models and to refine a new pictorial language. After the blazing experiments of Fauvism and the structural challenges of the years that followed, his Nice period focused on serenity and clarity. Instead of radical fragmentation, he pursued synthesis—bringing figure, décor, and atmosphere into a single, harmonious whole. “Woman Leaning” belongs to this phase, when Matisse explored how modest gestures and familiar furnishings could sustain a painting’s entire emotional weight. The years around 1923 are especially rich in half-length portraits of women seated by windows or screens, each a study in the conversation between a living face and the ornamental world around it.

Subject and Pose

The model’s posture is deceptively simple. Her head tilts into the palm of her right hand, elbow bent, shoulder eased forward. The left arm drifts across the torso, forming a soft diagonal that stabilizes the composition. This leaning gesture is not a sign of boredom; it is a visual hinge that locks the figure into the environment. The cheek pressed to the hand introduces a triangle of angles—wrist, jaw, and cheekbone—that play against the rounded rhythms of blouse and hair. The gaze is downward, almost dreamlike, and the eyelids are described with a few decisive strokes. Matisse is less interested in psychological narrative than in the state of reverie itself, that quiet pause when thinking and feeling merge. The pose, at once relaxed and alert, becomes the painting’s inner tempo.

Composition and Structure

The canvas is organized as a near-square field with strong verticals bracketing the figure: a dark band at left and a warm, terracotta column at right. These upright elements act like stage curtains, framing the sitter and preventing the space from dissolving. Between them, the woman occupies a central band, her head slightly off center to the right to counterbalance the weight of the darker left edge. The chair’s yellow slat and the red cushion in the lower left corner provide small anchors that keep the composition from floating away. Matisse handles the rectangle as a woven fabric, interlacing blocks of color and passages of bare canvas. The viewer’s eye moves in a gentle circuit from the dark mass of hair to the bright blouse trim, to the rosy column, and back to the face.

Color and Atmosphere

Color creates the mood before the subject is fully read. The dominant note is pink—varied from coral to dusty rose—which saturates the blouse and echoes softly in the wall’s floral marks. Pink here is not sweetness; it is warmth diffused. The right-hand column introduces a deeper, earthier orange that grounds the palette, while the left-hand vertical, a cool gray-brown, keeps the composition from becoming saccharine. The skin is modeled with a limited range of creams and muted siennas, just enough to describe planes without heavy shadow. Against this restrained flesh, the lipstick-red touches in the lips and the darker bracelets heighten presence. Matisse uses complementaries sparingly: greens and yellow-greens flicker among the floral strokes behind the figure, setting the pinks aglow without creating conflict. The overall effect is like a room at late afternoon—colors mellowed, edges softened, the air tinted by light.

Pattern and the Decorative Field

The background is neither window nor landscape; it is a decorative surface animated by brush-marks that suggest blossoms and leaves. These are not botanical illustrations but rhythms of paint that activate the wall. The ruffled edging on the blouse repeats the scalloped motion of the floral marks, so that garment and wallpaper share one ornamental logic. Matisse treats décor not as a backdrop added after the figure but as a coequal participant. Ornament democratizes the canvas: nothing is merely background, and the sitter’s presence is intensified by being in tune with her surroundings. The decorative field acts as both setting and echo, a softly pulsing chorus behind the solo voice of the face.

Drawing and the Economy of Line

Although color carries much of the meaning, drawing is crucial. The contour of the jaw is a single, confident sweep; the bridge of the nose is a minimal stroke that still tells us about volume and direction; the eyelids are flattened arcs that convey fatigue and reflection without descriptive fuss. The wristwatch is a small black oval and a quick band—barely there, but sufficient to suggest modern life and time’s gentle pressure. Around the blouse, the rickrack-like edge is built from repeated zigzag touches, lively but controlled. Matisse’s line is never fussy. It is the memory of touch—quick, sure decisions that preserve the freshness of a first impression.

Light and Paint Handling

Light in “Woman Leaning” is ambient rather than directional. There is no overt sunlight raking across forms, yet the whole picture glows. Matisse achieves this with thin, breathable layers of paint and by allowing patches of ground to remain visible, especially along the left edge. The sensation of air arises from these light, porous applications. In the face, he uses small shifts in temperature—cooler notes along the eye sockets, warmer along the cheek and chin—to model without sculpting. Brushwork in the blouse is more extroverted, with ruffled accents laid down decisively and then left alone. This contrast between the quiet face and the lively garment keeps attention where it belongs while still honoring the pleasure of painting fabric.

Psychology and Mood

What does the woman think? Matisse does not specify. The lowered gaze and the cheek in hand invite associations—daydreaming, listening, resting, remembering—but the painting avoids narrative closure. The mood is contemplative and tender rather than melancholic. The softness of the palette, the gentleness of the drawing, and the absence of harder shadows create a space of repose. The figure’s inner life is present as atmosphere rather than as a defined story. This restraint is part of Matisse’s modernity: emotion is conveyed through formal means—color intervals, line rhythms, spatial compression—rather than through theatrical expression.

The Role of the Interior

Matisse’s Nice interiors are arenas for the exploration of intimacy. A chair, a swatch of wallpaper, a window blind, a scrap of lace—these are not domestic trivia but instruments in his orchestra. In “Woman Leaning,” the room functions like a frame of mind. Its floral wall, red cushion, and warm verticals offer a calm environment that mirrors the sitter’s inwardness. Unlike grand historical spaces, this interior is not meant to impress; it is meant to cradle. The painting suggests that the modern subject finds meaning in rooms scaled to human feeling and decorated for delight rather than prestige. The interior is a theater of everyday grace.

Comparisons Within the Nice Period

Placed alongside the more opulent odalisques of the mid-1920s—full of patterned screens, carpets, and props—“Woman Leaning” feels modest and near. The model is clothed, the palette is lighter, and the format is intimate. Yet the ambitions are similar: to fuse figure and décor into a single pictorial breath. Where the odalisques orchestrate long arabesques and saturated reds, this painting prefers the quiet pulse of pinks and creams. It reveals a complementary facet of Matisse’s project in Nice: the possibility that introspection and decorative joy need not be opposites. In this picture, the lavishness of pattern becomes a gentle music rather than a spectacle.

Material Presence and Scale

The small scale of the work matters. It invites close viewing and rewards the eye with painterly details that would be lost in a larger format. One sees the grain of the canvas at the left edge where the paint thins, the slight drag of the brush at the ruffled hem, the way a single loaded stroke lays down both color and contour along the jaw. The thickness of paint varies: thinner in the wall, more substantial in the blouse and hair. These differences create tactile variety, like textures in a room—plaster, cloth, wood—translated into paint. The objecthood of the painting, the feel of color as substance, becomes part of its intimate charm.

Space Without Illusionism

Matisse reduces perspective to a minimum. There is no deep recession; instead, space is a shallow box held together by verticals and patches. This refusal of conventional depth lets color relationships dominate and makes the sitter feel near, as if sharing our air. The leaning pose compresses the figure further into the plane, the forearm sliding across the torso to prevent any thrust outward. Yet the painting never feels flat in a dead sense. It breathes through layers: floral wall behind, figure in the middle, chair slat at the margin. The result is a space calibrated for attention rather than for spectacle.

Time, Rhythm, and Looking

The painting’s tempo is slow and humane. Repeated motifs—the scalloped blouse edge, the scattered blossoms—create a gentle beat that guides the eye without pushing. The viewer’s gaze lingers on the face, drifts along the arm, pauses at the wristwatch, returns to the lips, and then wanders through the wallpaper’s soft marks. Nothing rushes; nothing stalls. Matisse’s rhythm is that of quiet companionship, the kind of time one spends near a friend who is lost in thought. The picture teaches a form of looking attuned to small changes, to the way one color warms another, to the way a line can be firm yet tender.

Modern Beauty and the Everyday

“Woman Leaning” proposes a modern beauty grounded in the ordinary. There is no spectacle, no heroic posture, no myth. The blouse’s playful trim might be handmade; the chair is simple; the room is familiar. Beauty arises from the alignment of the sitter’s inwardness with the room’s affectionate color. In this sense, the painting is democratic. It suggests that dignity belongs to anyone seated by a window with thoughts drifting, that a humble interior can sustain pictorial grandeur when handled with care. Matisse’s radicalism here is his confidence that gentleness is enough.

Influence and Legacy

Works like “Woman Leaning” shaped later understandings of how painting can be both decorative and profound. The Pattern and Decoration movement looked back to Matisse’s Nice period for permission to exalt ornament. Painters fascinated by color—Bonnard in a neighboring generation, and later Diebenkorn, Fairfield Porter, and Jennifer Bartlett—found in these interiors a model for how to build luminous pictures from ordinary rooms. Even outside painting, the image reverberates: designers and photographers have borrowed Matisse’s method of letting garments and wallpapers converse, of allowing a single hue to steer mood. The legacy is less about a specific icon and more about a way of seeing—an ethics of attention to modest beauty.

How to Engage with the Painting Today

To meet this picture on its own terms, begin by noticing the pinks. Let your eyes register the variations from blouse to wall to column. Then move to the face: the slight asymmetry of the eyes, the small highlight at the tip of the nose, the way the lips hold color without dominating. Watch how the ruffled edge constructs a path along the shoulders and sleeve. Allow the floral marks to blend and separate as your focus changes. With each circuit, the painting becomes less a portrait of a particular person and more an image of a feeling—the sanctuary of a quiet afternoon. In the pace of contemporary life, this slowness is not nostalgic; it is restorative.

Conclusion

“Woman Leaning” condenses Matisse’s Nice-period ideals into a serene, intimate statement. It shows how a simple pose can carry complex harmonies; how color, when tuned to human warmth, can build atmosphere; how pattern, rather than competing with the figure, can amplify presence. The painting invites the viewer to dwell in a room where thought and sensation are held gently together. Neither grand nor austere, it is an ode to everyday inwardness, proof that painting can make the ordinary glow with a quiet, enduring light.