Image source: wikiart.org

Historical Context And The Nice-Period Pivot Toward Clarity

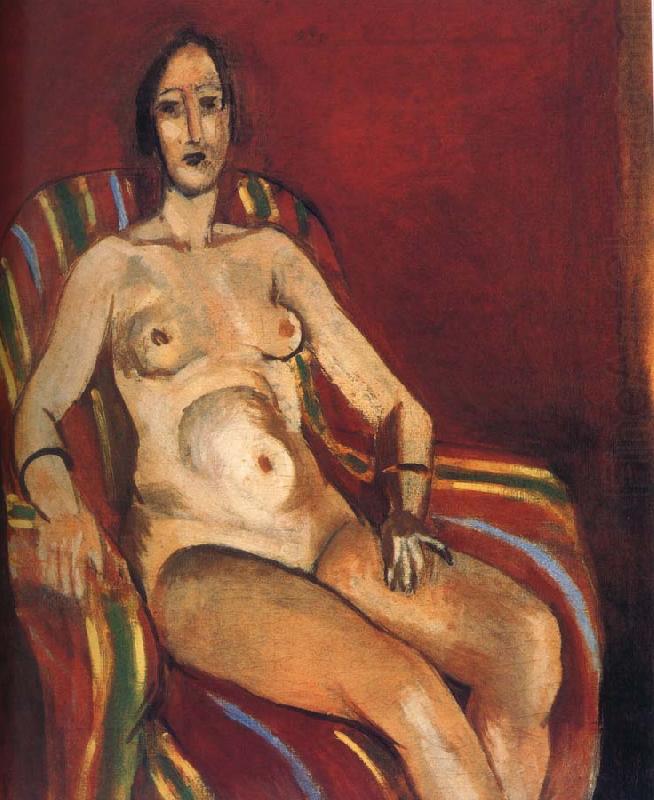

Painted in 1923, “Nude in Front of a Red Background” belongs to Henri Matisse’s Nice years, when he reoriented his art around an even Mediterranean light, simplified planes, and interiors treated as instruments for color. The Nice period is often remembered for languorous odalisques and airy window scenes, yet this canvas shows a tougher register within the same program. A monumental nude occupies an armchair striped with green, yellow, and blue, while a great wall of red closes the space around her. The result is both intimate and declarative: a classic subject—the seated nude—recast through modern structure and a concentrated palette.

A Composition Engineered From Blocks And Bands

The picture’s architecture is legible at a glance. The left third is dominated by the model and her striped chair; the right two-thirds recede into a largely unbroken field of red. The body builds a wedge that projects from the lower left toward the center. This thrust is stabilized by the chair’s stripes, which ride up the armrests in rhythmic bands and then sweep behind the torso like a low parapet. The head sits just inside the top left quadrant, keeping the figure from feeling top-heavy, while the right knee advances into the foreground to anchor the composition’s lower edge. Everything is designed to balance a large, quiet red with a compact, sculptural figure.

The Red Field As Climate And Structure

Matisse’s red is not a backdrop; it is a climate. Brushed in slow, semi-opaque layers that let warm undertones throb through, the red establishes emotional temperature and spatial pressure. Because the wall is so wide and so uniform, it registers as a plane close to the picture surface. The nude is therefore not staged before a deep vista but held within a shallow chamber of color. This deliberate shallowness suits Matisse’s emphasis on relation rather than illusion—how flesh reads against red, how stripes cut the field, how the body’s warm and cool passages tune themselves to the surrounding air.

The Pose: Monumental Stillness With Subtle Counter-Motion

The model sits with legs parted and right arm relaxed along the chair arm. Her left forearm crosses the belly, introducing a gentle diagonal counter to the torso’s verticals. The head turns slightly toward the viewer, the face simplified into masklike planes that hold their own against the saturated wall. The pose is frank but not aggressive. It makes the body’s architecture available to paint: the long oval of the thigh, the bowl of the belly, the keel of the sternum, and the square of the shoulders. Matisse converts this anatomy into a sequence of readable shapes, classical in clarity, modern in compression.

Drawing That Lives Inside Color

Contour is crucial, but it is never a prison. Black and brown lines swell and thin as they pass around forms—heavier along the near thigh, lighter at the cheek, boldly insistent at the left wrist. These living lines register the artist’s hand as it searches and decides. In the torso and belly, line often seems to retreat so that color modeling can take over: pale, chalky warms meet cooler violets and greens to turn the volumes. The face is defined by a few decisive signs—arched brows, a straight wedge of nose, compact mouth—sufficient to fix expression without weighing down the painting with anecdotal detail.

Color Chords: Warm Flesh, Cool Stripes, And The Red Atmosphere

The palette is a compact chord. Flesh tones carry peach and terra-cotta warmed by the red climate, then cooled by slate grays and small olive shadows where forms turn away from light. The chair brings a complementary counterpoint: green, yellow, and blue stripes that temper the room’s heat and keep the figure from dissolving into the wall. Because the stripes pass under the flesh and echo around the body, they bind figure and ground into a single field. Metal bracelets and hair are deepened to near-black, giving the composition its lowest notes and helping the warm skin register as light-bearing, not merely light-struck.

Light As A Continuous Veil Rather Than Spotlight

Matisse avoids theatrical highlights. Illumination arrives as a steady veil that clarifies planes by temperature rather than by harsh contrast. Subtle cools gather beneath the breast and along the lower abdomen; warmer notes lift the cheekbone and the round of the knee. The red wall, brushed broadly, receives this same even light, which is why it can support the nude rather than compete with it. The sensation is of a room that glows—the lightness seems to pile up in the figure while the wall hums with stored warmth.

The Armchair: Ornament That Behaves Like Architecture

The striped armchair is the painting’s quiet engineer. Its bands are not mere flourish; they channel eye-movement, contour volume, and measure the space behind the body. Where the stripes bend, the viewer feels the cushion’s give; where they rise toward the upper back, they become a kind of colonnade that emphasizes the figure’s height. The stripes’ greens and blues serve as the principal cools in the picture, counter-weighting the red and ensuring that flesh can heat up without overheating. As in so many Nice-period interiors, pattern is a structural device.

Space Built By Overlap And Weight

Depth in this painting is constructed through overlap and chromatic weight, not through linear perspective. The near thigh overlaps the chair’s cushion and pushes forward; the forearm sits squarely on the armrest; the head rides just in front of the chair’s back; and the chair itself sits before the red wall. Even in the red, Matisse varies value and saturation slightly so the lower right seems to recess, while the red nearest the figure feels denser. Space is shallow but stable—a perfect stage for the drama of color relations.

Rhythm, Repetition, And The Eye’s Loop

The painting is choreographed as a looping path. The gaze meets the face, then moves down the sternum to the bowl of the belly, where circular modeling echoes the round of the breasts. From there the eye presses along the near thigh and knee, ricochets across the chair’s striped arc, and returns along the far arm to the face. Repetition keeps time: round to round, band to band, vertical to vertical. The few accents—a dark bracelet, a notch of shadow at the neck, a blue seam within a stripe—work like percussion, pricking the rhythm without interrupting it.

Material Presence: The Pleasure Of Varied Touch

Surface handling distinguishes materials without literal description. The red field is laid with long, soft strokes and thin scumbles that let earlier layers breathe through. The chair’s stripes are firmer, often dragged with a quarter-dry brush that leaves bristle trails like fabric nap. Flesh is a complex skin of thin veils and thicker passages that allow undercolor to glow at the edges. In the hands and face, strokes slow and tighten; in the wall they loosen and speed. These variations of touch make the painting tactile; you feel air, textile, and skin though nothing is pedantically “rendered.”

The Nude Reimagined For Modern Clarity

Matisse situates this work within the long tradition of the seated nude yet strips it of allegory. There is no mythic pretext, no narrative prop. The model’s presence, the chair’s pattern, and the red climate suffice. This constraint is the source of the painting’s modernity. Rather than dramatizing desire, Matisse dramatizes relation—how a body sits within a carefully tuned environment of color and light. The result is dignified, frank, and unsentimental.

Psychology Of Stillness And Authority

Though simplified, the face communicates a calm authority. The slight asymmetry of the eyes and the concentrated mouth produce a composed, unsmiling attention. The squared shoulders, weighty thighs, and planted arm suggest stability rather than languor. The red climate amplifies this psychological temperature: red here reads not as alarm but as presence, a confidence that fills the room. The portrait is neither coy nor confrontational—its strength is in its steadiness.

Kinship And Contrast In The 1923 Corpus

Set beside contemporaneous Nice interiors—odalisques amid carpets, window scenes with sparkling sea—this canvas is austere. It pares the palette to red, flesh, and a disciplined spectrum of stripe colors; it reduces furnishing to one chair; it flattens space to a chamber. Yet it shares the Nice-period fundamentals: pattern as structure, light as continuous veil, drawing that lives inside paint, and a humane tempo that invites long looking. The austerity intensifies these principles, letting the viewer feel their logic undistracted.

Design Lessons: Balancing Heat And Calm

The painting offers durable design lessons. A single dominant field—in this case red—can structure an entire composition if countered by calibrated cools and by clear shape design. Repetition at multiple scales (bands on the chair, circular modeling in the body) stabilizes complex color. Cropping tightly can heighten presence as long as internal rhythms keep the eye circulating. Most of all, modeling by temperature rather than black-and-white contrast yields forms that feel luminous and alive.

The Viewer’s Experience Of Time

At first glance the picture appears blunt: nude, red wall, striped chair. On a second look, micro-events emerge—a cool seam circling the navel, the faint green that collects under the breast, a rosy reflection on the inner thigh where the stripe color bounces into the flesh, a near-invisible revision to the contour at the left wrist. On the third circuit, the painting transforms from object to performance: the speed of strokes in the wall, the corrections left visible in the arm, the slow blending around the knee. Time in the image lengthens through attention rather than story.

Conclusion: A Clear Chord Of Flesh, Stripe, And Red Air

“Nude in Front of a Red Background” condenses Matisse’s Nice-period ideals into a powerful, distilled chord. A monumental figure, a single patterned support, and a field of saturated color are tuned to an even light so that the painting breathes without flourish. Nothing distracts from the essentials: the calibrated pressure of red, the structural intelligence of the chair’s stripes, the humane modeling of the body. It is a portrait of presence, not posture—modern because it achieves depth of feeling through clarity of means.