Image source: wikiart.org

Historical Context Of A Nice-Period Masterwork

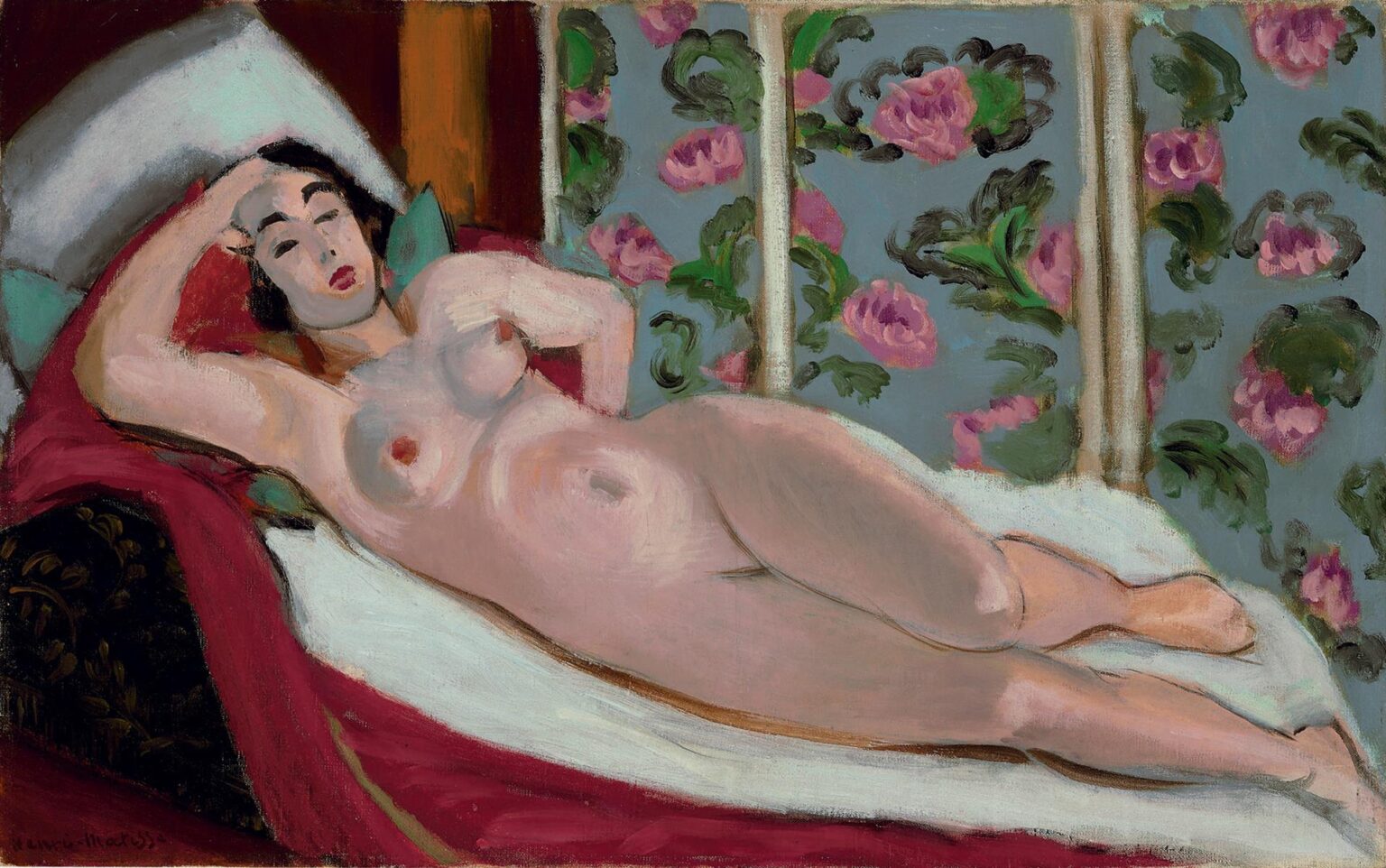

Henri Matisse painted “Nude on a Chaise Longue” in 1923, at the height of his Nice years, when he transformed rented rooms along the Côte d’Azur into luminous theaters for color, pattern, and the human figure. After the blazing experiments of Fauvism and the structural rigor of the 1910s, Matisse sought a language of sustained clarity: forms simplified into legible planes, an even maritime light that allowed color to breathe, and interiors arranged so pattern became architecture. The reclining nude, a subject with a lineage from Titian to Ingres, became his laboratory for this new clarity. In this canvas, the figure’s long diagonal pose, a rose-patterned screen, and plush red bedding are orchestrated into a poised harmony that favors presence over narrative.

The Composition’s Diagonal Engine

The design is built around a strong left-to-right diagonal. The model reclines from the upper left, where her head rests on a pillow, to the lower right, where her legs taper toward the edge. This diagonal is not allowed to slide out of the frame because Matisse braces it with countervailing elements. A sequence of vertical window or screen uprights divides the rose-blue background into steady bands, acting like a colonnade that holds the diagonal in place. Triangular pillows and swathes of crimson bedding provide wedge shapes that lock the torso and hips to the couch. The chaise itself is leveled by a crisp band of white sheet that cuts across the lower third, a horizontal that calms the slant and clarifies the plane on which the body lies. The result is a composition that reads instantly at a distance yet reveals small structural decisions upon close viewing.

Pose And The Poise Of Ease

The model’s left arm curls behind her head, the right bends at the elbow to support a gentle turn of the torso, and the hips roll forward to lengthen the flank. The pose produces a sequence of soft angles rather than a single serpentine line, giving the body internal architecture. The head tilts toward the viewer, with eyebrows arched and lips a compact rose note. Nothing strains. Matisse’s Nice figures do not perform; they inhabit. Here the model’s ease sets the tempo for the whole painting, inviting a gaze that lingers on relations of color, light, and curve rather than on anecdote.

Pattern As Architecture Rather Than Ornament

Behind the figure rises a screen of stylized roses painted in a restricted vocabulary of blue-gray ground, pink blooms, and dark green leaves. Scaled larger than life yet kept shallow by their flat handling, the roses turn the wall into a structural sheet. The screen’s vertical stiles deliver measured intervals that counter the chaise’s diagonal. In the left corner a dark decorative panel sits beneath the pillow, its deep tones adding a necessary bass to the picture’s register. Pattern here is not garnish. It frames, measures, and supports the body while binding background and figure into a single climate.

Color Chords And The Temperature Of Calm

The palette is a tuned chord that favors warm skin notes and cool surrounds. Flesh is built from peach, shell pink, and pearly gray with hints of lavender where the form turns away from light. The chaise longue wears a mantle of saturated crimson that catches small reflections of skin and green. The sheet’s white is not pure; it floats between cool blue and warm cream, preserving the harmony of the room’s light. The background’s blue-gray quiets the red and heightens the warmth of the body, while the roses’ pinks echo the color of lips and nipples, weaving background to figure. Small cool triangles of green pillow and leaf deliver strategic counterpoints that keep the composition from overheating. Because every hue is pitched to the same climate of light, the eye can travel without jolt.

Light As An Even Maritime Veil

The illumination is signature Nice period. Rather than dramatic spotlights, a continuous, oceanic light softens edges and allows volume to be expressed through color temperature. Highlights collect gently on shoulder, breast, and thigh, but never blaze. Shadows are chromatic, not black: bluish grays under the arm, mauves along the hip, olive notes at the flank. This gentle veil lets the body feel both present and breathable, with transitions that read as air rather than contour lines. The sheet absorbs the light like chalk, the velvet reds of the coverlet deepen toward the edges, and the screen stays luminous even within its cooler register.

Drawing That Lives Inside The Paint

Matisse draws with the loaded brush, letting edges swell and thin as forms turn. The contour along the belly is a living seam where warm flesh meets the cooler sheet; the knee is stated by an economy of planes rather than an inventory of anatomical detail; the hand behind the head dissolves into a few decisive angles because its job is to assert gesture, not to showcase fingers. Facial features are laid with calligraphic brevity: a straight wedge for nose, arched strokes for brows, almond lids, and a compact mouth that provides a focal red. Everywhere, drawing and color are inseparable, which keeps the surface elastic and modern.

Space Built By Planes, Overlaps, And Angles

Depth is shallow by design. The white sheet acts as a flat plane tilted slightly toward the viewer, the red coverlet falls over it in heavier folds, and the nude overlaps both, projecting forward without using exaggerated perspective. The floral screen sits as a patterned wall with enough vertical divisions to keep it from floating. Overlaps do the spatial work more than vanishing points: arm over pillow, hip over sheet, thigh over border of couch. This closeness suits the painting’s intention—an intimate stage for color relations—while still granting room for air and breath.

Rhythm, Repetition, And The Eye’s Path

The painting invites a looping path of attention. The gaze meets the face, slides down to the beaded nipples that act like small rhythmic beats, drifts across the belly’s cool center toward the thigh, then follows the sheet’s light band to the left where crimson rises and repeats the curve of the flank. From there it lifts to the roses in the screen, whose circular forms echo the figure’s rounded volumes, and returns along the model’s arm to the face. Repetition keeps time—circular blooms and breasts, vertical stiles and arm segments, diagonal chaise and reclining body—while color motifs recur like a melody: pinks in flower and flesh, greens in pillow and leaves, blue-grays in wall and shadow.

Material Presence And Tactile Hints

Matisse’s touch differentiates materials without descriptive fuss. The red coverlet is laid with thicker, saturated strokes that leave bristle ridges and imply plush fabric. The sheet’s whites are thinner, scumbled so that the ground peeks and reads as woven cotton. The screen’s roses are quick, buttery dabs that feel like paint on plaster rather than botanical illustration. The skin’s surface is a complex glaze of warms and cools, softly blended but never airless, so the figure appears to glow from within. These tactile contrasts ground the composition in bodily memory even as the forms remain simplified.

The Nude Reimagined For Modern Clarity

“Nude on a Chaise Longue” participates in the long history of the reclining nude, yet its modernity lies in method rather than myth. There is no allegory, no narrative pretext. The subject is presence—the lived relation among body, textile, and patterned wall under an even light. Matisse’s economy strips away anecdote so that the viewer can savor how a single diagonal of flesh holds its ground against a measured screen, how a red field deepens the warmth of skin, how a white band steadies a room.

The Role Of Red As Emotional Structure

The crimson bedding is more than color; it is an emotional armature. It warms the lower register, provides dramatic contrast to the cool wall, and reflects faintly into the underside of the figure, producing a blush that reinforces life. Because the red is tempered by the blue-gray background and by broad passages of white sheet, it never overwhelms. Instead it gives the picture its inner heat, the sense of intimacy that defines the Nice interiors. This is how Matisse organizes feeling: not through gesture, but through the placement and proportion of color fields.

Facial Expression And The Mask Of Calm

The model’s expression appears serene, almost masklike, with arched brows and a small, decisive mouth. This clarity is functional. A highly detailed face would unbalance the painting’s economy. By simplifying the features, Matisse ensures that the face can hold its own against powerful fields of red and blue-gray without becoming a competing drama. The masklike treatment is not detachment; it is concentration. It gathers the figure’s presence and allows the rest of the body to act as a continuous, legible form.

Kinship With Other Works From 1922–1924

Set beside Matisse’s odalisques and interiors of the same years, this canvas holds the center of that sequence. It shares with “Odalisque Reclining with Magnolias” the diagonal couch and patterned wall, but here the palette is more restrained and the decorative flora are rendered as a repeating screen rather than a vivified bouquet. Compared to the more ornate rooms with carpets and screens multiplied, this work feels distilled. It is closer to a musical trio than a full orchestra: body, bedding, and screen, each given a clear part.

The Viewer’s Time In The Image

The painting expands through attention. On first encounter, one reads the long diagonal of the nude and the floral wall. On a second pass, the subtle modulations surface: a cool lavender pooling below the ribcage, a narrow brown seam where thigh meets sheet, a pale green triangle of pillow wedged between head and wall, a faint reflected pink on the sheet’s edge near the hip. A third pass draws out the painter’s hand—the loaded stroke that defines the breast, the quick leaf-flicks in the roses, the slower drag of white across the sheet to flatten its plane. The picture is engineered to give back as much as the viewer gives it.

Why The Canvas Still Feels Contemporary

The work remains fresh because its modernity is grounded in clear decisions. Scale is controlled so complexity stays legible: large fields of red and blue-gray support medium motifs of roses and small accents of facial features and nipples. Color is tuned to a single light climate, allowing chroma to carry volume. Pattern behaves like architecture. Drawing lives within paint. These choices continue to inform painting, photography, and design today, proving that clarity is not minimalism but a generosity of relation.

Conclusion: A Lucid Chord Of Flesh, Fabric, And Floral Plane

“Nude on a Chaise Longue” distills Matisse’s Nice-period ideals into a serene, memorable chord. A diagonal body rests in a room where pattern steadies, red warms, white calms, and blue-gray cools. Light arrives as a continuous veil that lets color do the modeling. The nude is neither myth nor anecdote; she is a presence in a tuned environment, an invitation to look slowly and to find pleasure in relations perfectly judged.