Image source: wikiart.org

Historical setting and the Nice-period ideal

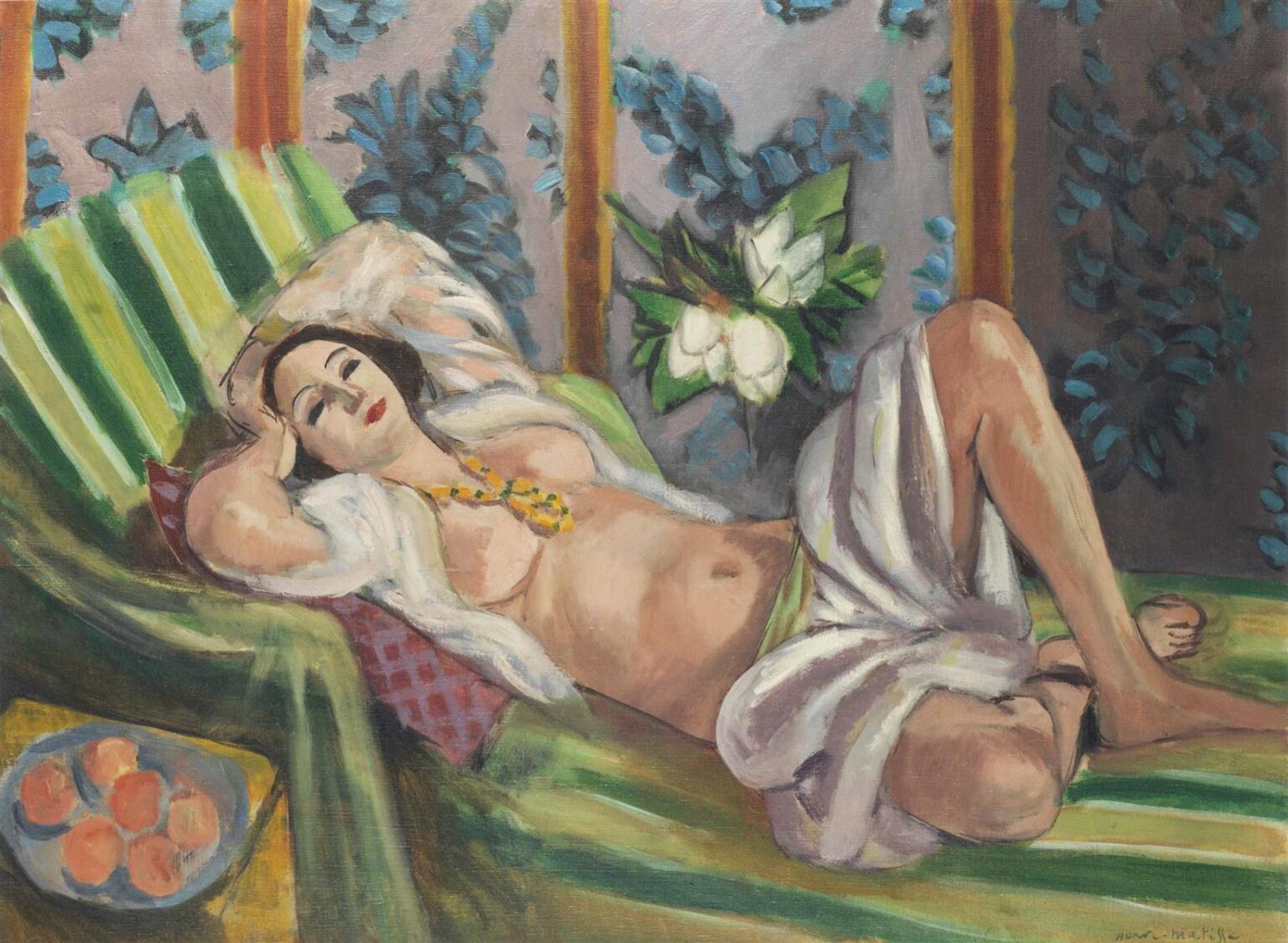

Henri Matisse painted “Odalisque Reclining with Magnolias” in 1923, at the height of his Nice years. In these Mediterranean studios he pursued a new clarity after the high-voltage Fauvism of 1905–1908 and the structural rigor of the 1910s. The goal was a sustained lyricism: even, maritime light; legible, simplified forms; pattern that behaves like architecture; and figures posed not to act but to inhabit. The odalisque became his favored motif because it allowed a continuous play between body, fabric, and ornament, a modern echo of the reclining nudes that thread through European painting from Titian to Ingres. In this canvas Matisse compresses the entire program into one lucid stage: a woman reclining on a green-striped divan, magnolia blossoms shimmering on the wall behind her, and a small bowl of peaches anchoring the near corner. Everything is arranged for long looking, where pleasure arises from relations rather than spectacle.

Composition as a diagonal stage

The design reads instantly at a distance because Matisse builds it from explicit diagonals and calm counterbalances. The model lies along a strong left-to-right diagonal, head at the upper left, knees raised toward the lower right, her body turning gently as it travels. The divan’s stripes repeat that diagonal, quickening the movement while preserving order. Behind her, vertical screen panels and a patterned ground of leafy forms press forward as steady pillars, keeping the diagonal from sliding off the picture. A cluster of white magnolias sits near the figure’s torso, an intentional hinge between background and body. At the lower left, a small square table with a bowl of peaches forms a stabilizing block, a counter-shape to the flowing curves of flesh and drapery. The entire composition locks together like a chord: strong slant, vertical buttresses, and one square note to ground the music.

The pose and the poise of ease

Matisse’s Nice models are never in a hurry. The odalisque’s left arm cradles her head; her right arm rests loosely at the hip; one knee lifts, the other leg turns away, creating soft angularities that keep the line of the body from becoming a single curve. The torso is not theatrically arched; it simply breathes. This poise matters because it clears space for color and pattern to speak without narrative noise. The necklace lays a deliberate rhythm across the chest, repeating in miniature the series of stripes and leafy rounds that populate the room. The tilted head, with its masklike features, greets the viewer with composed directness rather than coyness. The model’s ease establishes the picture’s tempo: unforced, balanced, and quietly sensuous.

Color chords and temperature control

The palette is a carefully tuned chord of greens, grays, creams, and peachy warms punctuated by small sparks of yellow and white. The divan’s green stripes are not one green but a scale—from olive to viridian to mint—so that fabric feels mobile under light. The background carries a cool violet-gray that hosts blue leaf-forms; these cooler notes create a soft air around the figure and allow flesh tones to read warmly without overheating. The magnolias deliver the painting’s brightest high notes: white petals edged with soft green shadows, amplified by a few sharper, lacquer-like leaves. The necklace provides an interior brass section of small yellows that gather the center of the composition. The bowl of peaches at the left corner is not an afterthought; its muted oranges echo the rosiness of the model’s cheeks and belly, weaving the near corner into the chromatic conversation. Nothing screams. Each color is pitched to the Nice climate of even light so that the eye can roam without jolt.

Pattern as architecture, not frill

What looks at first like decoration is the painting’s scaffolding. The divan’s green bands model volume as they bend and widen with the form, giving the recline depth and direction. The gridded red cushion behind the head adds a cross-rhythm, a small percussion against the large stripes. The wall is a screen of blue leafy arabesques set inside warm vertical bands; it functions like a colonnade, converting background into a plane that supports the figure rather than competing with it. Matisse learned from Islamic ornament that repetition can build space. Here the stripes, grid, and foliage form three interlocking rhythms—long, medium, and short—that make the room legible and alive.

Light as a continuous maritime veil

The illumination is quintessential Nice: soft, oceanic, and everywhere at once. Highlights do not carve; they breathe. Shadows are chromatic—lavender under the arm, cool olive in the hollow of the hip, blue-gray around the lifted knee. The body is modeled by temperature rather than by black-white contrast, which preserves both clarity and tenderness. The magnolias glow not because they are given neon edges, but because everything around them is tuned slightly dimmer; the whites read as light itself joined to matter. This even veil of light grants the picture its unhurried serenity.

Drawing inside the paint

Matisse’s drawing is carried by meeting edges of color and by the pressure of the loaded brush. The profile of the face is stated with a firm seam between warm flesh and darker hair; eyelids are quick, sensuous arcs; the nose is a simple wedge; the mouth a compact, rose-colored lozenge. The torso’s contour thickens at the flank and thins at the ribs, so the line breathes with the body. The drapery gathers at the hip in long, confident strokes, each turn reading as both fold and gesture. In the background, the leafy forms are written calligraphically—dark, tapering strokes that speed and slow so the screen feels alive. Because drawing lives within color, contours never harden into fences; forms remain flexible and fresh.

Space by planes, overlap, and angle

Depth here is achieved without theatrics. The near square of the table advances, but its angle aligns with the divan’s diagonal so that it supports the figure instead of colliding with it. The odalisque overlaps pillow, couch, and wall; the magnolia cluster overlaps the screen; the raised knee breaks toward us, while the torso glides back along the couch’s stripe. The space never deepens into a tunnel; it is a shallow, intimate stage designed for color relations to remain audible. You can feel your own body’s distance from the couch—no step backward or forward needed.

Rhythm, repetition, and the eye’s path

The painting is choreographed for a looping path of attention. You first meet the face and necklace, slide down the torso along a faint, cool shadow, reach the knot of fabric at the hip, bounce across the raised knee, drift into the green field of the divan, and then lift to the magnolias whose whites pull you back to the chest. On the next lap you notice the gridded cushion, the mirrored stripe angles, the faint reflected green along the belly’s underside, the peach echoes in the bowl. Rhythm is sustained by recurring shapes: rounded beads and peaches, ovate leaves and breasts, lengthened stripes and limbs. The canvas becomes visual music with bass lines in green, treble flutters in white, and midrange chords in flesh and gray.

Material presence and tactile distinctions

The pleasures of touch are everywhere. The divan’s stripes are laid with thick, elastic strokes that leave bristle ridges like the nap of fabric. The wall’s foliage is slightly drier, catching the canvas weave so ornament sits like paint on plaster. The magnolia petals are smoother, their soft blends imitating the waxen flesh of the flower. Skin is a veil of thinly fused warms and cools, gentle enough to preserve luminosity; the white drapery is built from crisp, broken whites that crinkle at the edges. These tactile differences make the scene persuasive without resorting to descriptive fuss.

Magnolias as motif and metaphor

The white blooms are not merely decoration; they are the picture’s emblem of freshness. Their scale—the largest blossoms on the wall—pulls the eye to the center, keeping the odalisque linked to the backdrop. Symbolically, magnolias carry connotations of purity and voluptuous scent, a perfect counterpoint to the painting’s measured sensuality. Matisse places them near the body’s midpoint, where waist turns to hip, as if to suggest an exchange between plant and person, blossom and breath. Their whites also clarify the value range, letting every other color assume its role without confusion.

The odalisque reconsidered

Matisse’s odalisque belongs to a long European fascination with the harem image, yet his treatment is less about fantasy than about pictorial order. The room reads as an invented climate more than an exotic locale. Pattern is disciplined; the body is presented with dignity and calm. The balance between sensual materiality and formal clarity is the modern note: a nude who is not an anecdote, a setting that is not a story, a harmony that feels contemporary because it is built from relations anyone can track—warm to cool, diagonal to vertical, curve to stripe, bloom to face.

Kinship within the Nice sequence

Compared to the darker, carpet-laden odalisques of earlier years, this 1923 canvas is airy and architectural. The diagonal couch and vertical screen recall his window pictures, while the bowl of fruit nods to the studio still lifes of the period. What distinguishes this work is how decisively the magnolias join figure and field. Matisse often sought a single device to lock the parts—a sash of color, a patterned rug, a window bar. Here the blossom cluster performs that task with disarming elegance.

The viewer’s time in the picture

The image holds attention by offering discoveries proportional to patience. After the initial read, small marvels surface: a quick mint stroke that defines a fold on the drapery’s crest; a lavender seam under the breast that turns volume without calling attention to itself; a faint, cool reflection along the inner thigh produced by the nearby green stripes; a thin, yellow line of frame that warms the wall’s verticals; a shadowed notch at the wrist that anchors the head. The painting expands not by narrative chapters but by accumulative relations that keep rewarding the eye.

Why it still feels contemporary

A century on, the canvas remains fresh because its modernity lies in method rather than motif. Patterns are scaled and distributed so complexity stays legible. Colors are tuned within a single climate so harmony prevails without blandness. Drawing breathes inside paint. The figure is present and respected, not consumed by story. These are durable lessons for any visual field—from design to photography to painting today.

Conclusion: a lucid chord of body, blossom, and stripe

“Odalisque Reclining with Magnolias” condenses Matisse’s Nice-period ambitions into one serene chord. A body at ease, a room organized by pattern-as-architecture, blossoms placed as luminous hinges, and color tuned to an even Mediterranean light yield an image made for return. Nothing is forced, yet everything is decided. The pleasure it offers is the pleasure of relations perfectly judged—how white meets green, how diagonal meets vertical, how flesh meets air—so that the canvas breathes with the quiet confidence of a song you can hum after one hearing and keep discovering for years.