Image source: wikiart.org

Historical Setting: The Nice Years And A Return To Radiant Clarity

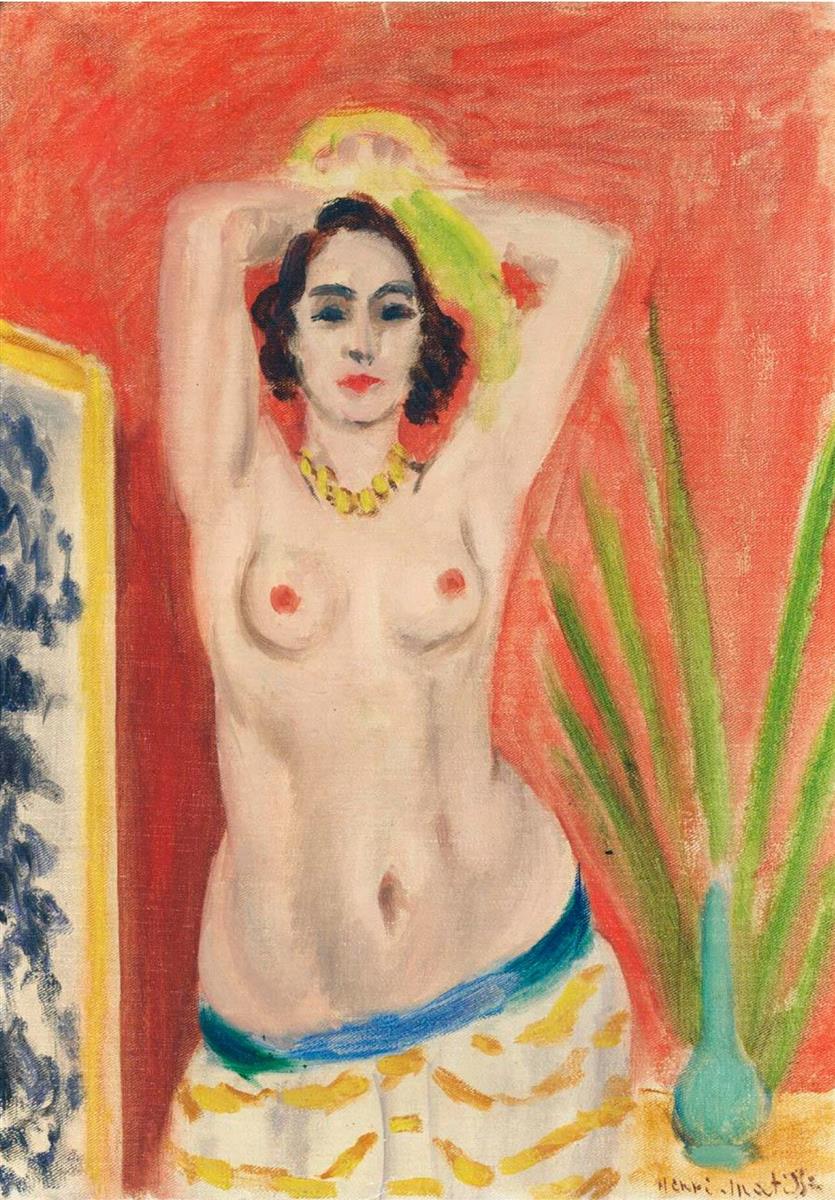

Henri Matisse painted “Nude Torso” in 1923, right in the middle of his Nice period, when he transformed rented rooms on the Côte d’Azur into laboratories for light, color, and the human figure. After the high-voltage experiments of Fauvism and the structural rigor of the 1910s, his aim in Nice was different: he wanted pictures that were clear, breathable, and built for sustained looking. “Nude Torso” embodies that ethos. Cropped boldly at the thighs and crown, the composition isolates the model’s upper body against a hot, coral-red wall, flanked by a patterned screen at left and a turquoise vase of green fronds at right. A yellow necklace, a sash of cool blue, and a skirt scattered with golden dashes create a compact orchestra of accents around the central, softly modeled flesh.

Composition: A Cropped Stage For Color And Gesture

The painting’s structure is frank and frontal. The model stands with arms raised behind the head, a classic stretching gesture that lengthens the torso and opens the ribcage. That upward sweep sets the main vector: a tall vertical column of skin running from the blue sash at the hips to the head, with symmetrical arcs of arms that act like parentheses. Matisse crops high and low so that the body presses against the picture plane; there is no wasted perimeter. The left border introduces a narrow strip of patterned panel with a yellow frame, a vertical counterweight to the palm fronds and vase that ground the right side. This left–right pairing acts as bookends, keeping the central body steady while preventing the field of red from becoming monotonous. The turquoise vase sits close to the lower right corner and sends a splayed fountain of leaves upward, echoing the arms’ gesture in vegetal form. The result is a stable triangle whose apex is the model’s head and whose base stretches between the skirt’s hem and the vase.

The Figure’s Pose: Poise Without Performance

Matisse’s Nice models rarely act; they inhabit. Here the figure’s expression is composed and direct, with a slight lift in the chin and a compact, confident mouth. The raised arms are not theatrical display but a pretext for clarifying form: the gesture tightens the abdomen, defines the curve of the ribcage, and creates soft hollows in the armpits where cool grays meet warm pinks. The pose lets the painter describe the torso as a series of slow turns rather than a collection of anatomical facts. The necklace, a linked circle of lemon-yellow beads, gathers the chest and fixes a rhythmic center between the two round accents of the breasts. The hips cant subtly to the model’s left, introducing a counter-curve that keeps the column of the body from becoming static.

Color Chords: Red Climate, Cool Counterpoints, And Golden Sparks

Color carries the painting. The dominant field is a saturated coral-red wall that behaves like a climate more than a backdrop. Matisse lays it with sweeping, semi-opaque strokes that let the weave of the canvas breathe through, so the red glows instead of shouting. Against this warm environment he places calibrated cools: the blue sash at the hips, the turquoise vase, a pale yellow-green halo of scarf or cloth near the head, and cool shadows in the torso built from pearly grays and blue-violets. Small, high-keyed accents—the necklace’s yellow, the lipstick-like red of the mouth, the golden dashes on the skirt—act as sparks within the red atmosphere. The palette is limited yet tuned: each hue has a job, either cooling the space, warming the flesh, or punctuating the rhythm.

Pattern And Ornament: Structure, Not Frill

Two decorative elements frame the body. At left, a vertical panel bordered in yellow encloses loose, dark-blue scribbles; this sliver reads as a painted screen or a secondary canvas and performs two tasks: it breaks the red plane and sets a deep, inky note that calibrates the value scale for the entire picture. At right, a tall turquoise vase launches green, blade-like fronds that arc up the wall. Their long diagonals repeat the arms’ sweep and point back toward the face and chest, knitting the edges to the center. The skirt—or sarong—around the hips is off-white, scattered with rhythmic brush-dabs of ochre. Those dashes mimic the necklace beads in a different register and, together with the sash, stabilize the bottom edge like a base molding in architecture.

Light: A Continuous Mediterranean Veil

The illumination is the Nice period’s signature: soft, maritime, and even. There is no theatrical spotlight—no violent highlights or black shadows. Volume is described by temperature shifts: a warmer blush along the sternum, a cooler drift under the breasts, a faint violet on the flanks where the torso turns away. The effect is relaxed and humane; the body appears to breathe within the red air. On the vase, Matisse thins the paint so the glaze catches a matte gleam; on the wall, he drags strokes dry to let the ground scintillate; on the skin, he floats thinner veils that create pearly transitions. Light here is not a problem to solve but a kindness that lets color talk.

Drawing Inside The Paint: Edges That Flex And Breathe

Instead of hard outlines, the figure is drawn by meeting edges of color. The contour along the left waist thickens where the belly turns and thins near the ribs; the breasts are stated by circular, elastic strokes that carry just enough emphasis to feel round; the hands dissolve into soft planes behind the head, because their job is to push gesture, not to showcase anatomy. The face is a compact, modern mask—arched brows, shadowed lids, succinct nose wedge, small red mouth—sufficiently summarized to withstand the red field’s pressure. Everywhere the brushwork remains legible: you can see the load, the speed, and the turn of the wrist, which keeps the surface lively even in calm zones.

Space: Shallow Depth, Strong Presence

The room is shallow by design. The red wall sits just behind the figure; the patterned panel touches the left edge; the vase roots the right edge to the floor plane. Overlaps, not perspective, create order: the body overlaps wall and screen; the fronds overlap wall; the skirt overlaps sash. This near space makes the nude feel present, almost within reach, and keeps attention on relations of color and rhythm rather than on architectural recession. The slight angle of the screen and the way the fronds foreshorten toward the top are enough to prevent flatness while preserving frontality.

Rhythm And Repetition: How The Eye Moves

The image is choreographed as a loop. The viewer’s eye strikes the mouth and necklace, slides outward along the collarbones to the round accents of the breasts, descends to the cool blue sash, bounces off the skirt’s ochre dashes, moves right to the turquoise vase, follows the green fronds upward where they hook back into the head and raised arms, and then returns to the face. Along this route, repeated shapes keep time: circles (necklace beads, nipples, yellow halo, vase mouth), long diagonals (arms, fronds), and dashes (skirt, incidental brushmarks in the wall). Color repeats too: blue in sash and the screen’s dark scribble; yellow in necklace and skirt; green in halo and plant. The rhythm is steady but not mechanical, full of small syncopations that reward repeated viewing.

Material Presence: Tactile Cues And The Pleasure Of Paint

The painting’s sensuality is as much tactile as visual. The red field shows dry-brush scumbles that expose canvas texture; the torso’s transitions are wet-in-wet merges that feel soft to the eye; the necklace beads are small, raised dabs; the plant fronds are brisk, elastic strokes that fray at their ends; the skirt’s ochre marks are laid quickly, their edges imperfect, imitating the randomness of printed cloth. These distinctions of touch prevent the color fields from becoming inert and anchor the composition in lived material—skin, ceramic, fabric, plant.

The Nude Reimagined: From Academic Display To Modern Presence

By cropping the body and pairing it with decorative elements used as structural tools, Matisse modernizes the centuries-old nude. There is no myth, no anecdote, no elaborate setting. The figure is a living architecture that holds color; the room’s objects—screen, vase, leaves—function as counterforms and color engines; and the viewer’s engagement is with relations rather than narrative. This shift turns sensuality into clarity: pleasure is found in seeing how warm skin rests in a red climate cooled by turquoise, how a necklace’s yellow stabilizes the chest, how green leaves rhyme with raised arms.

Comparisons: How “Nude Torso” Sits Within The 1923 Sequence

Placed beside other Nice works from 1922–1924, “Nude Torso” is among the most concentrated. Where many paintings showcase patterned carpets, draped couches, and long views through windows, this one compresses the set to three actors—screen, plant, and body—and a single dominant wall color. It shares with the odalisque series the love of ornamental accents and the ethic of ease, but it pushes frontal cropping further, closer to a poster’s immediacy. The palette, too, is distilled: one big warm field answering a few strategic cools, with just enough neutrals in the flesh to keep the chord humane.

The Viewer’s Path: How The Picture Lengthens Time

A quick glance gives the subject—standing nude, red wall. A second look begins the circuit: face to necklace to chest to sash to vase to fronds to arms and back. A third look reveals the micro-decisions: the blue sash’s thicker edge on the lit side; a violet-gray pooling under the left breast; a pale greenish halo that softens the crown of the head and keeps hair from fusing with the hot wall; the way the yellow frame of the screen quietly calibrates brightness across the canvas. With each pass, time in the picture expands, not by narrative but by accumulated relations.

Design Lessons: Why The Image Feels Balanced And Fresh

Several devices keep the balance. First, a dominant field (red) is countered by two cool anchors (turquoise vase, blue sash). Second, edge elements (screen, fronds) are scaled to the body: narrow enough not to compete, strong enough to stabilize. Third, accents repeat in different registers (yellow necklace and skirt marks; blue sash and left panel’s dark writing), preventing any one note from feeling isolated. Fourth, the raised-arms gesture gives the figure an internal architecture that the surrounding diagonals can echo. These decisions make the painting legible at a distance and engaging up close—a durable modern clarity.

Meaning Without Anecdote: Presence, Heat, And Ease

“Nude Torso” doesn’t narrate; it proposes a state—of warmth, poise, and ease. The red wall suggests coastal heat; the turquoise vase and green fan leaves whisper a breeze; the model’s relaxed strength makes the room feel hospitable. The painting’s generosity lies in how simply it achieves this: a handful of colors, a few props, a clear pose, and brushwork that records perception in motion. The result is not a copy of reality but a tuned environment where body and color keep each other company.

Conclusion: A Clear Chord Of Body, Red Air, And Cool Counterpoint

In “Nude Torso,” Matisse distills his Nice-period ambitions into a lucid, compact harmony. A standing figure, cropped for immediacy, inhabits a red climate steadied by a turquoise vase and a blue sash. Pattern acts as structure; light arrives as a continuous veil; drawing breathes inside paint. Nothing is labored, yet everything feels decided. The canvas proves how a few well-judged relations—warm to cool, curve to band, accent to field—can turn a simple scene into a lasting modern presence.