Image source: wikiart.org

Historical Context And The Riviera’s Quiet Stage

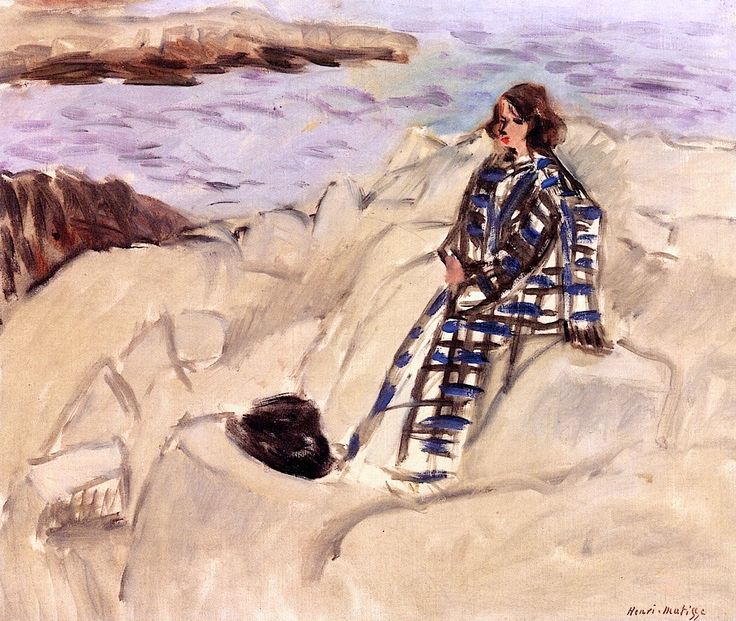

Henri Matisse painted “Marguerite Ad Antibes” in 1922, during the mature Nice years when the French Riviera became his studio of light. These seasons were dedicated to balance rather than bravura—color tuned to a steady climate, forms simplified to planes, and figures placed within rooms or coastal landscapes that read like lucid stages. The sitter is Marguerite, Matisse’s daughter, a recurring presence across his career and an anchor for some of his most searching portraits. Setting her on the pale rocks above the water at Antibes, he fused two strands of his work: the intimate portrait and the plein-air seascape. The result is not a topographic souvenir but a meditation on presence, light, and the velocity of brushwork that keeps the scene alive.

Composition As A Meeting Of Figure And Shore

The painting is engineered around a broad diagonal of pale rocks that runs from lower left to upper right, lifting the figure into the upper third where coast and sea open out. Marguerite sits in profile three-quarter view, turned slightly toward the water, her torso vertical against the sloped terrain. A second diagonal—her wrapped coat and dropped arm—interlocks with the stone’s geometry, creating a stable hinge at her seated hip. A dark cap or rock near the foreground functions as a counterweight, pinning the base of the composition and giving the eye a place to start before climbing toward the figure. Behind her, the shoreline stacks into horizontal bars—near water, farther rocks, lilac sea—so that the image toggles between diagonal ascent and horizontal calm. Everything is arranged to bring the gaze repeatedly back to Marguerite while never severing her from the place.

The Figure’s Pose And The Poise Of Attention

Marguerite’s posture is one of unforced attentiveness. She sits comfortably within the irregularities of the rock, knees bent, hands loosely gathered, shoulders relaxed. The head tilts a fraction toward the horizon, suggesting watchfulness rather than reverie. Her presence is not dramatic; it is grounded. This poise underwrites the painting’s mood: the model is neither a decorative accent nor an anecdotal tourist. She is a calm vertical chord set against the Riviera’s pale geology, a human rhythm that allows the landscape to speak.

The Coat As A Portable Pattern

The eye is immediately drawn to the blue-and-black geometry of Marguerite’s coat. Matisse uses its striped-check structure like a mobile tapestry draped across the irregular stones. The coat’s pattern plays several jobs at once. It articulates the figure’s form without resorting to fussy modeling; it supplies the strongest chroma in the picture, a saturated blue that announces the artist’s long memory of Fauvism; and it provides a counterpoint to the soft, uninflected planes of rock. The garment’s repeated bars rhyme with the sea’s small wavelets and with the distant ledges of coast, knitting figure and site into one system of marks.

Color Chords And The Temperature Of Calm

The palette is a chord of cool violets, pale warms, and decisive blues. The rocks are laid in creamy grays tipped with peach and beige, their warmth kept in check by lavender shadows that collect in fissures. The sea is a sheet of lilac and slate broken by brief, horizontal strokes of lighter tone—enough to state motion, never enough to break serenity. Against this quiet climate, the coat’s cobalt and ink-black accents arrive as clarifying notes, echoed subtly in the sitter’s hair and in the dark foreground cap. The face and hands are built with gentle apricots cooled by gray-violets, so that flesh feels part of the same air as stone and water. Nothing screams; everything breathes.

Drawing Inside The Paint And The Authority Of Strokes

Matisse’s drawing here is carried by the velocity of the brush. Stone edges are described with quick turns and soft breaks; the figure’s profile is a single, assured arc that spares detail to preserve life. The coat’s pattern is executed as rapid, calligraphic bars and rails, some closing into grids, others dissolving as the fabric curves around the body. The hands are concise, stated by a few planes and knuckles; the hair gathers in dark, elastic strokes that hold the head firmly in space. These decisions keep the surface vibrating. You can feel the painter’s hand mapping the terrain in real time.

Light As A Soft, Coastal Envelope

The illumination is even and maritime. There is no hard spotlight, no theatrical shadow. Instead, the rocks accept a pearly light that shifts temperature as planes turn; the sea carries a faint lavender cast that suggests high cloud or late afternoon; the figure is lit enough to maintain clarity without losing membership in the scene. Because light arrives as a continuous veil, color carries mood and volume. A narrow band of slightly cooler tone under the chin indicates shadow; warmer notes along the cheek and nose deliver the human warmth within the coastal cool.

Space Constructed By Planes And Overlap

Depth is achieved with economy. The near rock ledge occupies the foreground; Marguerite overlaps it decisively to affirm her seat in space; a darker head-shaped form fixes the front edge; the midground rocks step back as flatter planes; and the violet sea recedes as a single field, capped by the faint horizon of distant coast. There is little linear perspective; instead, value and temperature—warm near rock against cool mid rock, saturated coat against faint sea—do the work. The space stays shallow enough for intimacy but wide enough to feel the open air.

The Riviera Landscape As Modern Field

Rather than build the water from descriptive waves, Matisse reduces the sea to a modern field of coordinated marks. Short horizontal slips of paint calibrate the surface, while patches of lilac and slate suggest light’s passage. Distant rocks are simplified to brown slabs that float tonally between sea and shore. This approach treats landscape not as a subject to be copied but as an occasion to organize a sheet of color into a living surface. The result is faithful to sensation without being bound to detail.

Portraiture Without Insistence

Although Marguerite is a familiar and beloved subject, the painting sidesteps psychological insistence. The face is legible yet purposefully generalized; what matters is relationship—head to sea, coat to rock, figure to air. This restraint avoids the trap of anecdote and elevates the portrait to a broader meditation on presence. The viewer senses character through posture, chroma, and placement rather than through facial description, a strategy consistent with Matisse’s Nice ambition to make identity arise from the larger harmony of a scene.

Rhythm, Repetition, And Visual Music

The canvas’s pleasure is rhythmic. Long, soft diagonals in the rock repeat across the surface; rectangular bars of the coat recur at varying densities; horizontal beats mark the water and the far ledges. Color motifs return in new registers: darks in hair and coat pattern, blue chimes in garment and sea, pale warms in stone and skin. The eye follows a reliable loop—foreground dark, rock planes, coat pattern, face, horizon, back to the coat—and every circuit reveals new syncopations: a cooler notch along a fold, a warmer patch at the cheek, a faster touch where surf meets rock.

Material Presence And Tactile Cues

The paint handling leaves tangible traces that link sight to touch. The rocks are scumbled so that underlayers flash through, imitating the chalky, granular character of limestone; the sea is laid with thinner strokes that feel slick and mobile; the coat receives heavier, sticky pigment, appropriate to wool or woven cloth; the face gets thinner veils to protect its softness. These material contrasts keep the image rooted in bodily experience while sustaining the overall clarity of the design.

The Wind, The Coat, And Weather As Gesture

Even without explicit flags or foam, the painting hints at weather. The coat’s pattern flickers with speed, as if a light wind were worrying the fabric; the brush’s diagonal pulls across the rock imply forces that scraped and shaped the shore; the sea’s horizontal slips carry a small shiver. Within this subtle meteorology, Marguerite’s composure stands out. She is steady among moving elements, the human anchor of the coastal stage.

Connections To The Nice Interiors

Placed beside the interiors and odalisques of the same period, this outdoor portrait shares a crucial grammar: large calm planes, a few decisive accents, and a climate of even light. The rocks take the role of a white table or wall; the sea becomes the cool, patterned backdrop; the coat substitutes for the ornamental rug or textile; and the sitter retains the quiet authority seen in Matisse’s room-bound figures. The continuity underscores how the artist thought less in categories of “landscape” or “portrait” than in problems of relation—figure to field, warm to cool, curve to band.

The Viewer’s Path And The Experience Of Time

The painting choreographs a slow tour for the eye. You step onto the near rock, pause at the dark cap, climb the pale planes to the patterned coat, rest at the face turned toward water, drift across the lilac sea to the distant ledges, and circle back along the diagonal of stone. Each lap takes a little longer as you begin to register the micro-decisions: a flick of blue that closes a fold, a smear of violet binding shadow to sea, a warm echo of skin tone repeated faintly in the rocks. Time extends not through narrative but through attentive seeing.

Why The Image Still Feels Contemporary

The canvas remains fresh because it proposes a clear method for joining people to place without sentimentality. A few planes of tuned color, a pattern treated as structure, and brushwork that records perception in motion—these are tools that still guide painters and designers today. The portrait offers a model of composure in an open world: you can face the horizon and remain yourself; you can belong to the landscape without dissolving into it.

Conclusion: A Human Chord In A Coastal Key

“Marguerite Ad Antibes” is a quiet summit of Matisse’s Nice period. A daughter sits among chalky rocks while the violet sea breathes behind her; a blue-black coat supplies the pictorial bass line; swift, assured brushwork binds figure and shore into one chord. Light arrives as a soft envelope; color carries structure; pattern behaves as architecture. Nothing here is insistent, yet everything is memorable. The painting offers a durable lesson in how a person and a place can share the same calm air.