Image source: wikiart.org

Historical Context And The Nice-Period Language Of Calm

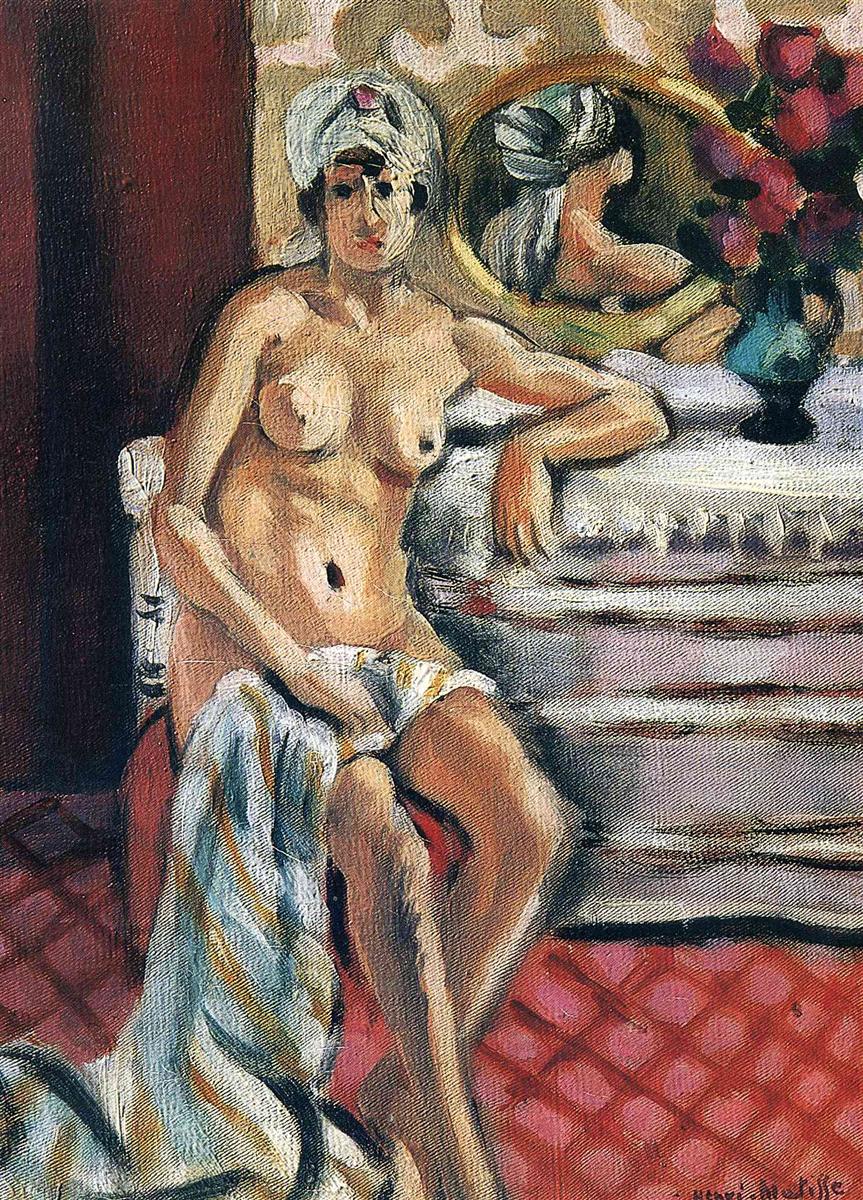

Henri Matisse painted “Nude in a Turban” in 1922, in the heart of his Nice period, when small hotel rooms, patterned carpets, mirrors, and a soft Mediterranean light became the dependable grammar of his art. After the audacity of Fauvism and the structural experiments of the 1910s, he sought a poised clarity in which color, line, and light would cooperate rather than compete. The odalisque theme—nudes or semi-nudes set among textiles and studio props—offered a flexible stage for those aims. In this painting a seated model wears a white turban set with a jewel, leans against the arm of a chair, and rests before a dressing table with mirror, vase, and flowers. The scene is intimate but not theatrical; it is meant to test how a human body, a few patterned planes, and reflective surfaces can be tuned into one balanced chord.

Composition As A Triad Of Figure, Mirror, And Table

The picture is built on a compact triangular armature. At the left edge a dark vertical panel creates a proscenium that pushes the figure forward. The nude occupies the center, her torso angled toward us, legs crossed and drapery falling in a diagonal cascade. To the right, a white table stacked with horizontal bands and fringes balances the vertical mass of the body. Above it, an oval mirror catches the model’s back and the twist of her turban, multiplying the figure while keeping the room shallow. The floor’s tiled red pattern recedes just enough to seat the chair and anchor the cascade of fabric. The overall geometry is frank: a tall vertical body, a low horizontal table, and a rounded mirror that echoes breast and shoulder. The eye travels a loop—face to mirror, mirror to vase, vase to table edge, table edge to drapery, drapery back to the face—learning the room by rhythm rather than by measurement.

The Model’s Pose And The Ethics Of Ease

Matisse’s Nice models rarely perform; they inhabit. Here the sitter reclines into the chair with the calm of someone at home in her body. One arm lies across the chairback as if it had found the most natural resting point; the other hand gathers the striped cloth that slips across the thigh. The crossed legs create a spiral that returns the viewer’s gaze to the torso. The turban—white with a rose jewel—crowns the head and establishes the highest note in the composition, both literally and chromatically. The expression is not seductive or coy; it is quietly present, allowing the viewer to adjust to the tempo of the room. This poise defines the Nice period: serenity made from pictorial decisions rather than narrative effect.

Color Chords And The Temperature Of The Room

The palette is a disciplined conversation among warm reds, creamy whites, and tempered greens and blues. The floor is a warm red lattice that hums beneath the composition, while the wall behind the mirror carries a tawny beige patterned with pale motifs that keep the surface alive without crowding it. The table and chair arm are rendered in whites that shift toward lilac and gray, crucial for catching the room’s soft light. Flesh tones move between apricot and pearl, cooled by blue-gray shadows under the breast, along the rib, and at the inner knee. The turban’s white sits at the painting’s top like a small cloud, its jewel delivering a compact burst of pink that rhymes with the flowers in the vase. These tuned correspondences keep the temperature steady: warm enough to be intimate, cool enough to be clear.

Pattern As Architecture Rather Than Decoration

Pattern in this canvas is never mere ornament. The red tiled floor establishes a grid that stabilizes depth and sets a walking tempo for the eye. The wallpaper’s pale motifs convert the wall into a patterned plane instead of a receding void, while the fringe and stripes on the table edge and drapery serve as metronomes, marking the transitions between body and object. Even the turban’s folds are painted as short, structural strokes that obey the head’s volume. Matisse absorbed lessons from Islamic art—repetition, symmetry, stylized motifs—and redeployed them as architecture for his modern interiors. The result is a room that reads as both decorated and disciplined.

The Mirror And The Double Of The Figure

The oval mirror is not simply a device for virtuoso reflection; it multiplies the figure and clarifies the composition. The mirrored back of the sitter tilts the gaze toward the right, restating the turban and necklace from another angle and linking the body to the vase and flowers. The mirror’s gold rim, a warm halo, frames the reflection like a cameo and sets a circular counterpoint against the table’s bands. Because the reflection is cropped, it avoids anecdote and behaves like a second figure held at bay by the oval’s contour. The double presence deepens the scene’s time: we experience both the model’s frontal calm and the memory of her turned away.

Drawing Inside The Paint

As in many Nice-period canvases, drawing here lives in the pressure of the brush inside color. The contour of the torso thickens and thins as the bristles pick up the weave of the canvas; the shoulder is modeled by a gentle shift from warm tone to cool, not by a separating line. The hand draped over the chair is summarized in a few confident planes that convince by angle rather than by finger count. The turban’s folds are flicks of white and gray calibrated to describe volume without fuss. The table fringe is a chain of succinct verticals that quiver just enough to suggest cloth. Everywhere drawing serves the painting’s tempo: decisive, supple, and unlabored.

Light As A Continuous Veil

The room is bathed in Nice’s soft maritime light, a continuous veil that refuses theatrical contrast. Highlights are modest: a lift along the collarbone, a slip of brightness on the top plane of the thigh, a glimmer on the vase’s shoulder. Shadows are chromatic rather than black, carrying violets and greens that keep the flesh breathing. Because illumination is even, color carries mood and volume. The white table is not cold; it holds gradations that echo the skin. The mirror’s glass is not a harsh glare; it is a warmer plane that accepts the reflection gently. Light here is a medium of hospitality.

The Drapery As Moving Contour

The striped cloth that falls from the sitter’s hand is a major actor. Its cool grays, whites, and yellow accents create a downward diagonal that balances the firm horizontals of the table. The way it pools on the tiled floor not only affirms contact with the ground but also dramatizes the fall from the lap’s warmth to the floor’s cooler geometry. In places the stripes dissolve into broad, wet strokes, and in others they sharpen at a fold. That alternation keeps the surface lively and the rhythm of the picture unbroken.

Space Built By Planes And Overlap

Depth is shallow and deliberate. The chair and figure occupy the near plane; the white table and mirror form the mid-plane; the wall pattern stays near, refusing deep recession; the dark curtain at left presses forward like a proscenium. Overlap declares order. The arm crosses in front of the table edge; the vase sits upon the cloth; the reflection recedes just enough to feel plausible. There is no theatrical perspective; the space is readable at a glance and can be lived with for a long time.

Rhythm, Repetition, And Visual Music

The painting’s pleasure is rhythmic. Circles echo—breast, jewel, mirror, vase foot. Short verticals repeat in the fringe and in the tiled grid lines. Curves return as the arc of arm, the oval mirror, the turban’s folds, the vase’s shoulder. Darks reappear at calculated intervals: hair, eyes, navel, vase base, mirror’s shadowed rim. These repetitions create a beat that guides the eye through a dependable loop, rewarding each pass with fresh inflections—a cooler notch under the rib, a warmer bloom on the shoulder, a small flash of pink among the flowers.

Material Presence And Tactile Cues

Matisse’s surfaces remain tactile even when simplified. You can feel the drag of the brush across the canvas tooth on the table’s white planes; you sense the thicker deposits of pigment in the floral bouquet; you read the turban’s crispness in the slightly drier strokes of white; you register the chair’s upholstery in soft, frayed edges along the arm. These material cues ground the image in touch and prevent the decorous setting from floating into mere design.

The Odalisque Theme Recast For Modern Eyes

The odalisque carries a nineteenth-century history of fantasy and voyeurism. Matisse modernizes it by compressing anecdote and elevating structure. The turban, mirror, and patterned floor acknowledge the genre, but they function as pictorial tools. The model’s gaze is frank, not theatrical; the body is an architecture of warm and cool planes; the mirror is a compositional instrument. The painting insists that sensual presence and compositional intelligence can coexist, a statement that keeps the work compelling today.

Relationship To Sister Works Of 1922

“Nude in a Turban” converses with other Nice-period interiors from the same year. Compared with the sprawling horizontals of his reclining odalisques, this vertical arrangement concentrates attention and heightens the role of the mirror. Compared with the airy coastal windows, it turns inward, swapping panorama for reflection. Yet the family likeness remains: an even light, a balance of large, calm planes with quick decorative beats, and a temperament of ease cultivated through exact choices.

The Viewer’s Path And The Experience Of Time

The canvas orchestrates a slow circuit for the eye. You meet the model’s face and jewel, follow the necklace to the shoulder, travel down the torso and across the draped cloth, touch the floor’s grid, climb the white table in steps, pause at the flowers, glance into the mirror for the doubled figure, and return to the sitter. With each circuit you notice new relations: the rhyme between jewel and flower, the echo between mirror oval and breast curve, the way a violet shadow binds arm to table. Time in the image expands through attentiveness rather than event.

Why The Painting Still Feels Contemporary

Its modernity lies in its clarity. With a handful of elements—figure, mirror, table, cloth, patterned planes—Matisse constructs a world that is both sensuous and lucid. Designers can learn from its grammar of big fields countered by small incidents; painters can study how drawing can live fully inside color; viewers can borrow its ethic of attention, which treats looking as a restorative act rather than a hunt for drama. The painting proposes that domestic space, seen with care, can be inexhaustible.

Conclusion: Presence Held By Pattern And Light

“Nude in a Turban” distills the Nice period’s best lessons. A seated figure rests in a shallow room; a mirror doubles her presence; a white table and red floor provide architectural calm; a cascade of cloth and a small bouquet keep the rhythm supple. Color carries structure, light arrives as an even kindness, and pattern works as architecture. Nothing clamors; everything agrees. The result is an image of enduring poise in which body, room, and reflection keep each other company in clear, modern harmony.