Image source: wikiart.org

Historical Context And The Nice-Period Turn To Poise

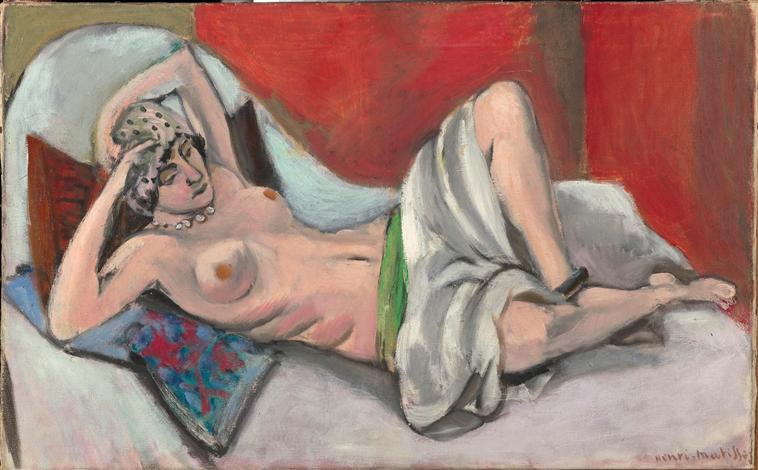

Henri Matisse painted “Draped Nude” in 1922, during the heart of his Nice period, when he transformed modest hotel rooms into measured theaters of light, pattern, and repose. After the flamboyant breakthroughs of Fauvism and the analytic pressures of the 1910s, he sought a new equilibrium built from lucid planes and tuned color chords. The odalisque framework—nude or semi-nude figure amid textiles and cushions—offered a flexible grammar for these experiments. “Draped Nude” exemplifies this ambition: the model reclines on a low divan, half wrapped in a pale drape, edged by red architectural screens that behave as large, stabilizing fields. Rather than offer anecdote, the picture investigates how a body, a few materials, and a softly coastal light can be organized into a clear, breathing harmony.

Composition As A Long, Reclining Arc

The structure is deceptively simple. A diagonal body extends from left to right, head propped on one arm and legs gathered loosely under a pale cloth. This long arc is countered by a sequence of perpendiculars: the back edge of the couch, the meeting of red wall and pale bedding, and the small right-angled silhouette of the far cushion. The head, breasts, navel, and knees establish a quiet rhythm of salient points along the arc; the green waistband at the abdomen acts as a hinge that anchors the midsection and prevents the figure from dissolving into a continuous sweep. The near pillow—patterned in blue and claret—forms a compact color island that steadies the left side, while the red screens flatten the depth and keep attention on the body’s contour rather than on recession. The overall effect is a poised seesaw between curve and plane.

The Nude As Architecture Of Ease

The model’s pose avoids theatrical languor in favor of self-possessed ease. One arm cradles the head without strain, the other rests along the hip; the pelvis tilts forward as the cloth gathers at the thigh; the feet relax rather than point. Matisse treats the body as an arrangement of volumes and temperatures rather than as an anatomy lesson. Shoulder and breast are built from warm half-tones cooled by bluish grays along the turning planes; the abdomen softens toward the drape; the knees are announced by simple, confident angles. Jewelry—a bead necklace and dark bracelet—adds small, pulsing notes that mark joints and centers, helping the eye keep time as it travels the length of the figure.

Color Chords And The Temperature Of Calm

The palette is a clear duet of warm reds and cool pearly grays, mediated by the body’s apricots and a decisive strip of green. The back wall or screen is a sustained chord of vermilion and carmine, varied just enough to feel spatial but stable enough to act as architecture. The bedding and drape inhabit a spectrum from cool pearl to lavender gray, absorbing and reflecting neighboring hues. Flesh emerges between these poles, reading as a living surface precisely because it is tuned between warm and cool, never forced into brittle contrast. The green waistband serves as the painting’s pivot: it tips the eye back toward the center, countering the red’s heat and giving the composition a chromatic hinge.

Light As A Continuous Coastal Veil

Nice-period light is a soft, maritime envelope rather than a spotlight. In “Draped Nude” this light slips across the drape, collects on the shoulder, and glides along the thigh in modest highlights that are really temperature lifts more than value spikes. Shadows are colored: the underside of the arm leans violet, the flank cools toward blue-gray, and hollows are never black. Because illumination remains gentle and continuous, color carries the expressive charge. The room feels inhabitable; the figure breathes.

Drawing Inside The Paint

Matisse draws with the pressure and direction of the brush, letting color edges carry structure. The breast’s contour thickens as it meets the rib cage, then thins across the sternum; the knee is a short, precise bend where warm and cool meet; the headscarf’s dots are quick, confident touches that read instantly without pedantry. Facial features are calligraphic—arched brows, a small nose ridge, compressed mouth—firm enough to hold likeness but soft enough to live within the painting’s general tempo. Throughout, the line is elastic and humane, never imprisoning the forms it describes.

Drapery As Moving Contour And Moral Of Modesty

The drape is not merely a covering; it is an instrument. Swept over the hip and thigh, it traces the leg’s lift, pools into folds that echo the couch’s curve, and introduces a veil of cool color that keeps the warm torso from overheating against the red background. Its edges flicker with small, high-key strokes where light catches creases, while broader, damp strokes generate velvety half-tones that mimic the weave of cloth. The drape mediates between body and stage, turning anatomy into rhythm.

Pattern And Plain In Equilibrium

Where earlier odalisques sometimes revel in dense pattern, “Draped Nude” chooses restraint. Pattern is concentrated in the headscarf’s dots and the near cushion’s blue-claret motif; both are scaled small and placed strategically: at the head to crown the reclining arc, and at the left to counterweight the rightward drift. The large planes—red screens, pale bedding—remain plain, allowing the figure to read clearly across distance. This balance between ornament and calm is key to the painting’s longevity; it invites attention without exhausting it.

Space Built By Planes And Overlap

The room is shallow by design. The divan’s curve occupies the foreground, the figure overlaps it decisively, and the red screen presses forward as a flat wall, refusing deep recession. The compositional truth is planar: a pale oval (couch) lies under a warm, modulated arc (body) before a red rectangle (screen). These planes meet at tangible seams—the back edge of the couch and the contact shadow under the thigh—so depth is felt without being measured. The viewer can read everything at once, the hallmark of Matisse’s modern clarity.

Rhythm, Repetition, And Visual Music

The painting’s durability lies in rhythm. Circular motifs recur as headscarf dots and cushion patterns; long curves repeat in arm, trunk, and couch; short right angles punctuate at the knees and elbow. Color echoes enforce the beat: the cushion’s claret answers the wall’s red; the scarf’s gray links to the drape; a dark bracelet rhymes with the shaded hollow at the far shoulder. The eye follows a dependable loop—face, necklace, breast, green hinge, knee, foot, drape fold, cushion, back to face—and each pass reveals a new syncopation: a cooler edge here, a warmer flare there.

Material Presence And Tactile Cues

However economical, the surface is tactile. The drape gains body where pigment is laid slightly thicker; the cushion’s pattern sits as small ridges; the red field shows the drag of a broad brush, recording the hand’s speed; flesh turns with thin, pearly veils that suggest living translucency. These cues keep the image grounded in touch. One can imagine the cool slip of cloth, the nap of the cushion, the warmth of skin against linen.

The Psychology Of Repose Without Fantasy

The odalisque has a long history of exotic fantasy. Matisse recasts it as a modern study of repose. The model’s expression is unforced, her gaze neutral, her body relaxed but alert—no narrative seduction, no melodrama. Jewelry and scarf function visually rather than theatrically; they mark nodes in the composition and admit small color sparks. The painting is frank about sensual presence while maintaining compositional intelligence, a balance that feels strikingly contemporary.

Relation To The Broader 1922 Odalisque Group

Compared with more ornate works from the same year, “Draped Nude” is spare and architectural. The great red planes anticipate the bolder color blocks of the 1930s, while the pearly modeling of flesh preserves the Nice period’s intimate light. Set beside “Nude With a Green Shawl,” this canvas tilts toward structural clarity rather than pattern luxuriance; set beside “Seated Odalisque,” it swaps frontal authority for the languid strength of a diagonal sweep. In the series, it reads as a hinge where sumptuous motif yields to planar economy.

The Viewer’s Path And The Experience Of Time

Matisse orchestrates a ritual of looking that lengthens time. The eye lands on the face and scarf, slips along the necklace to the breast, pauses at the green waistband, folds with the drape over the knee, touches the foot, returns across the cushion’s blue claret, and climbs the couch’s edge back to the head. Each circuit uncovers additional nuance: a warmer blush near the rib, a cooler streak in the drape’s shadow, a scumbled red seam that thickens the wall. The painting reveals itself by revisitation rather than by a single glance.

Why The Painting Still Feels Modern

Modernity here is not shock but clarity. With a limited set of elements—a body, a drape, two or three large planes of color—Matisse builds a complete and generous world. Edges carry drawing, color carries space, light carries mood. Designers still borrow this grammar of big planes plus a few tuned accents; painters study how volume can be stated with temperature shifts rather than theatrical chiaroscuro; viewers absorb a humane tempo of attention that resists both noise and puritanism.

Conclusion: A Clear Chord Of Body, Cloth, And Plane

“Draped Nude” distills the Nice period’s ideals into a lucid chord. A reclining figure spans the canvas; a pale drape turns anatomy into rhythm; a pair of red planes steadies the stage; cool pearly bedding and a precise green hinge tune the temperature. Brushwork remains supple and honest, light arrives as an even kindness, and pattern is deployed with restraint so the room can breathe. The painting’s promise is simple and enduring: within a few well-judged planes of color, a body and its surrounding air can agree.