Image source: wikiart.org

Historical Context And The Nice-Period Window

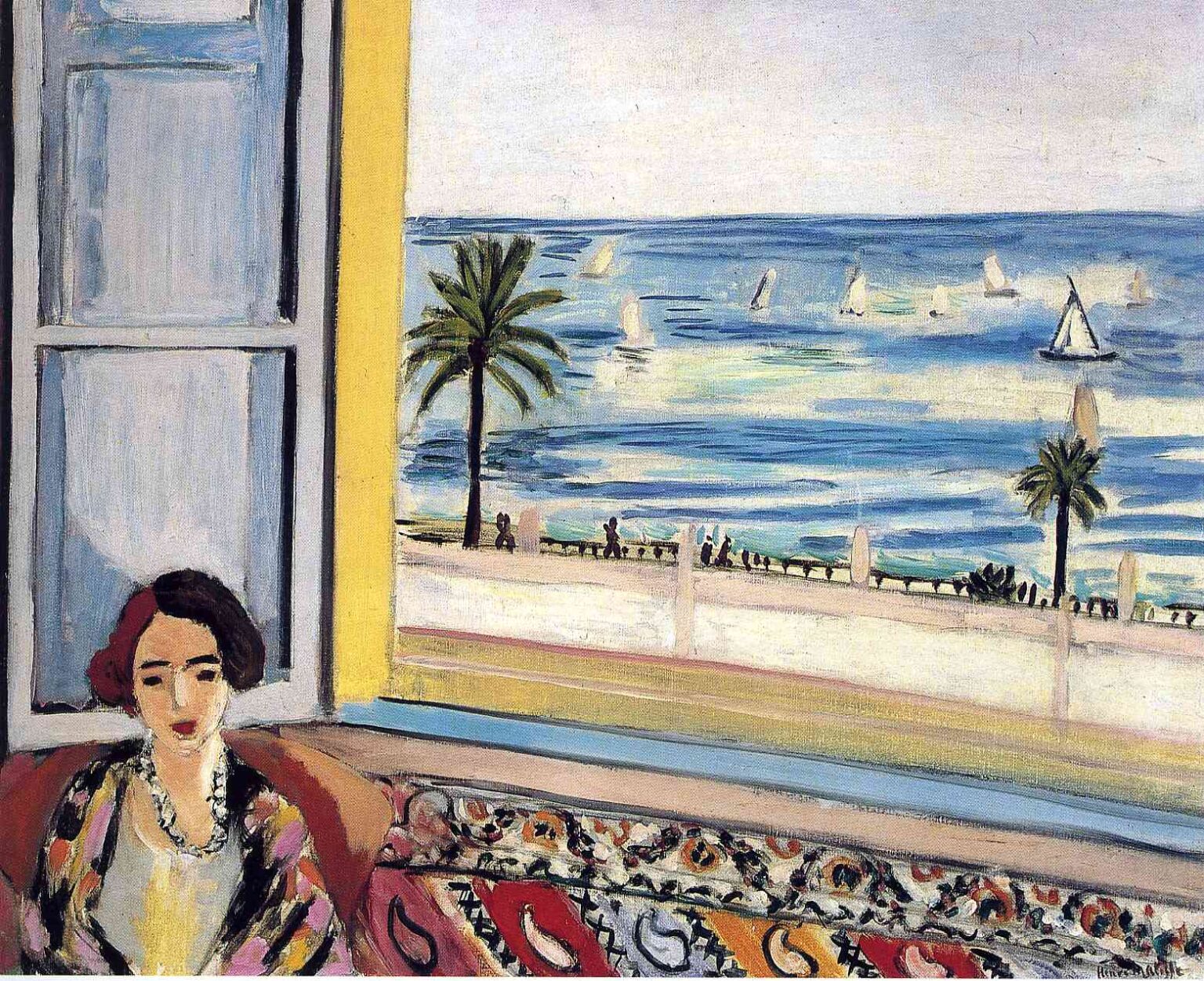

Henri Matisse painted “Seated Woman, Back Turned to the Open Window” in 1922 during his Nice period, when hotel rooms, balconies, and long, luminous windows became laboratories for a new language of calm intensity. After Fauvism’s blazing experiments, Matisse sought clarity without austerity, designing interiors where light arrives as a soft envelope and color operates as structure. The open window is his signature device in these years. It is both an actual source of Mediterranean light and a modern pictorial hinge that joins private space to the public world outside. In this canvas, the motif supports a poised duet: a richly robed woman occupying the left foreground and, to the right, an expansive view of palms, promenade, and a sea stippled with white sails.

Composition As A Double-Stage Of Interior And View

The painting divides itself into two interlocking stages. The first is the interior wedge at left: shuttered casement, sofa edge, patterned textile, and the seated woman’s head and shoulders. The second stage is the panoramic window that commands the remainder of the canvas, pushing outward toward horizon and sky. Matisse plants a vertical yellow jamb between the two, an emphatic bookend that holds their relationship steady. The woman is framed by the cooler, milk-blue shutter and the warm terracotta of the sofa, while the view is orchestrated in horizontal belts—pale promenade, dark palmlined strip, and the mobile, blue-silver surface of the sea. A patterned cushion or kilim spans the lower register, acting like a proscenium rail that confirms the foreground and keeps the eye from sliding out of the room. Nothing is accidental: the woman’s downward-turned gaze tempers the outward pull of the sea, and the quiet plane of shuttered glass balances the flicker of waves.

The Window As Structural Engine And Emotional Climate

For Matisse the open window is never mere scenery. It builds the picture’s geometry and governs its mood. Here the sash opens onto the Promenade des Anglais and the Baie des Anges, reduced to essentials: a bright shoreline, a procession of palms walking in silhouette, and a water field animated by bands of layered blues and quick white notations for sails and glints. The window’s broad rectangle behaves like a painting within the painting—cool, stable, and calm—while the yellow jamb and mauve sill register the way sunlight dyes architecture. Emotionally, the view sets the canvas in a key of airy optimism. The sea’s mobile surface, organized into tranquil horizontal bars, lends the entire room a steady breath.

The Seated Woman As Calm Counterpoint

Although the title emphasizes her back turning toward the window, the woman’s face is seen in three-quarter view, quietly luminous within a dark bob of hair accented by a single red patch. A necklace of pale ovals gathers the center, and a robe patterned in subdued violets, greens, and ochres throws soft drifts of color across her shoulders. She is neither distracted by nor enthralled with the view; she exists in a neighboring tempo to it, a human rhythm of quiet presence. The modeling is delicate, built from warm and cool transitions rather than hard shadow, so that the head reads as a living volume without sacrificing the planar clarity Matisse prized. Her posture—relaxed yet composed—confirms the Nice-period ethic: ease without slackness, serenity without emptiness.

Color Chords And The Temperature Of Clarity

Matisse’s palette here is a discipline in warm–cool balance. The interior stack gathers warm terracottas and ochres in the sofa and textile, moderated by the cool milk-blue of the shutter and the pearl-gray of the window’s inner face. The woman’s skin takes a gentle apricot illuminated by neighboring cools; her hair and the patterned robe carry deeper notes that ground the left side. Outside, the sea is built from slates and ultramarines crossed by pale turquoise and milky white scumbles, while the promenade is a pale ribbon punctuated by palm greens and near-black silhouettes. The yellow jamb, carefully pitched between lemon and ochre, acts as the necessary hinge between inside warmth and outside cool, the chromatic joint that keeps the painting’s temperature even.

Drawing Inside The Paint

No hard outline dictates the scene. Matisse draws with the pressure and direction of the loaded brush. The sash edges, jamb, and sill are declared as broad bands whose bristle marks hold just enough texture to suggest wood. The woman’s features are calligraphic—arched brows, a firm nose ridge, a short mouth—each placed decisively so the face breathes. The palm trunks outside are single vertical pulls set against the sea’s lateral movement; their crowns are swift radiations of dark green laid into wet blue. Sailboats are triangles and tilts of white that read instantly at distance. The patterned cushion in the foreground is a procession of motifs simplified to commas and ovals, the sort of ornamental shorthand Matisse could play by ear.

Pattern As Architecture Rather Than Ornament

Pattern saturates the lower edge in a kilim-like band whose reds, ochres, and black-blue accents march rhythmically across the picture. Instead of illustrating every stitch, Matisse extracts the rug’s structural beat: alternating emblems in bright registers that stabilize the entire foreground. This band both anchors the interior and echoes the promenade’s band outside; the two stripes—one textile, one urban—tie room and world together through repetition. Pattern appears again in the woman’s robe as softened patches that flutter rather than insist. The result is an interior that feels decorated yet never busy because pattern is used as an architectural device to meter space and weight.

Space Built By Planes, Bands, And Overlap

Depth is achieved without theatrical perspective. The sofa and kilim establish the near plane; the woman overlaps them to occupy the middle; the shutter and jamb articulate a local corner; beyond it the promenade and the sea flatten into layered belts. Overlaps perform most of the work: the necklace sits atop the blouse; the robe’s edge slides in front of the sofa; the palm trunks step in front of the sea’s striations. This planar construction keeps all actors present at once and allows the eye to move easily between near texture and distant breadth.

Light As A Continuous Coastal Veil

The illumination is the signature Nice light: a wide, soft veil that settles evenly on room and sea. Inside, it whitens the shutter, skims along the woman’s cheek and blouse, and warms the sofa edge. Outside, it lies on the water as a sequence of broken reflections described with horizontal strokes, each a small note of value change rather than a blazing highlight. Because the light is continuous, color carries the expressive burden. Warm and cool modulations tell you everything you need about volume, air, and time of day.

Rhythm, Repetition, And Visual Music

The picture’s lasting pleasure is rhythmic. Horizontal bars recur as sill, promenade, horizon, and the sea’s striations; verticals recur as jamb, shutter stiles, and palm trunks. Curves repeat in the sail triangles and in the patterned crescents along the kilim. Color returns in different registers: the red patch in the woman’s hair echoes small red emblems in the rug; the cool shutter blue reappears in a whitish band at the water’s edge; the yellow jamb is rhymed by warmer ochres in textile and skin. The eye traces a reliable loop: face, necklace, robe, kilim pattern, sill, palms, sails, horizon, jamb, shutter, and back to the face. Every circuit yields a new inflection—a cooler violet in the robe’s fold, a brighter flicker among the sails, a subtler green in the palm crown—so the painting remains fresh under long looking.

The Ethics Of Ease And The Absence Of Anecdote

One of the Nice period’s achievements is the conversion of everyday quiet into pictorial drama. There is no narrative here beyond the fact of a woman seated near a window and a sea alive with small craft. Matisse’s restraint is deliberate. He offers a model of attention rather than a story, asking the viewer to practice the same poised, sustained looking that the model herself seems to embody. Ease is not decorative softness; it is the disciplined arrangement of planes and temperatures so that the mind can rest while remaining alert.

The Sea As A Modern Field

In Matisse’s hands the Mediterranean becomes a modern field of marks. The water is not a literal transcription of waves; it is a sheet of coordinated strokes—horizontal, varied, and beautifully paced. The white sails are glyphs that activate the field without breaking it. Two dark palms punctuate the edge, registering the Riviera locale but, more importantly, supplying vertical beats against the lateral sweep. The sea’s modernity here is crucial: it allows the window to read as an abstract painting that happens to be a view, reinforcing the canvas’s thesis that room and world can share a single pictorial logic.

Material Presence And Tactile Hints

Even with his economy, Matisse leaves tactile signals everywhere. The shutter edges show the scuff of bristles dragged across slightly dry paint; the sofa’s terracotta reads as a matte, clothlike surface; the kilim motifs are pressed in thicker dabs that sit lightly on the surface; the woman’s blouse is painted thinly so underlayers glow through like fabric against light. The sea’s surface alternates thinner and thicker strokes, creating a low relief that catches illumination the way ripples do. These cues keep the visual music grounded in bodily memory—touch, weight, texture—even as the composition remains airy.

Relationship To Other Window Paintings

This canvas converses with a constellation of Nice-period windows and balconies. Compared with “Confidence,” which stages two women in quiet conversation before an open casement, the present work places more visual weight on the exterior world. Compared with the earlier Fauvist “Open Window, Collioure,” the 1922 picture tempers chroma and asserts planar architecture: shutter, jamb, sill, promenade. It anticipates later portraits in which the face, simplified to clear planes, holds its ground against strong patterned fields. Within the long arc of Matisse’s career, the painting marks a confident equilibrium—color still sings, but composition conducts.

The Viewer’s Path And The Experience Of Time

The painting choreographs a ritual of looking that gently dilates time. You begin at the calm oval of the face, trace the necklace’s chain to the patterned robe, drift across the kilim to the sill, step out onto the promenade, skim the palm crowns, catch the tiny sails with their tilts, rest at the horizon, and return along the yellow jamb and blue shutter to the woman. With each loop, you notice another echo, a new seam of color, a minute adjustment of proportion. The canvas does not demand; it invites, and the invitation can be accepted again and again.

Why The Painting Still Feels Contemporary

The work’s modernity lies in its clarity. It shows how a domestic room can be organized by a few strong planes; how a figure can coexist with an exterior view without becoming anecdotal; how pattern may stabilize space rather than distract from it; and how color, tuned rather than shouted, can carry both structure and emotion. Designers study it for its grammar of bands and blocks; painters study it for the way drawing lives inside paint; viewers keep it near because it offers an enduring tempo of attention in a noisy world.

Conclusion: A Room Where The Sea And A Face Agree

“Seated Woman, Back Turned to the Open Window” condenses Matisse’s Nice-period ideals into one lucid image. A woman’s composed presence, a patterned textile’s steady beat, and a window’s luminous panorama share the same stage. Color operates as architecture, light arrives as a continuous veil, and pattern becomes a structural rhythm. The painting’s promise is simple and rare: within a few planes of tuned color, interior life and the world outside can breathe together.