Image source: wikiart.org

Historical Context And The Southern Turn In Matisse’s Art

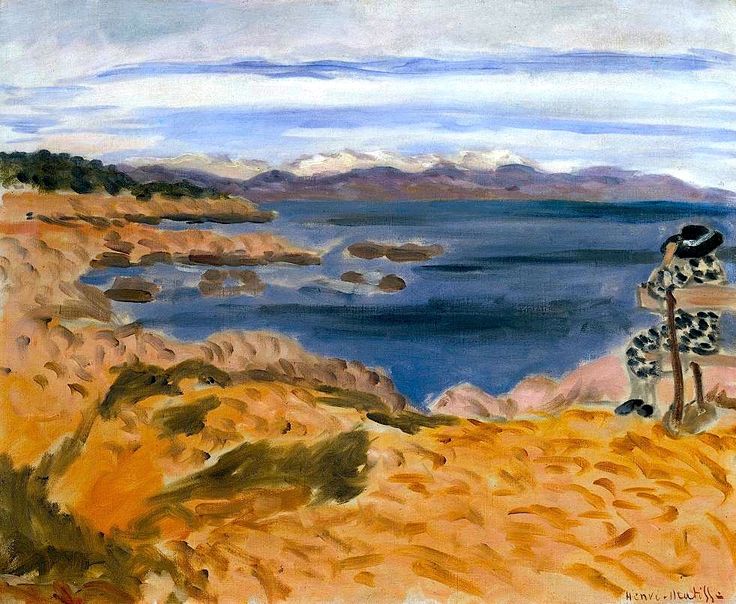

Henri Matisse painted “Cap D’Antibes” in 1922, in the thick of his Nice years when the Mediterranean coast served as both refuge and laboratory. After the convulsions of the 1910s, he committed to an art of lucid calm, building pictures from tuned color chords, clear planes, and a steady, unhurried gaze. Antibes, the promontory that thrusts between the Baie des Anges and the Golfe Juan, gave him a coastline of ochre rocks, scrubby pines, and water that shifted from slate to lapis in a single breeze. Here he could test how his interior language—large fields, rhythmic edges, and the soft envelope of light—translated into open air. The canvas belongs to that broader experiment: a wide view where the sea is a structural band, the rocks are a warm stage, and a single seated figure becomes a human metronome for distance and time.

Composition As A Three-Band Symphony

The composition divides into three broad registers that read from bottom to top like a musical score. The lowest band is the headland itself, a sweep of tawny ochres and olive shadows that arcs from the left foreground toward the right edge. It rises and falls in billows, the brush marking tufted grasses and rough stone without pedantry. The middle band is the water, a cool, expansive plane that bends around islets and shelves before deepening into a saturated blue toward the horizon. The upper band is the sky, a long, pale breadth brushed with horizontal veils of white and blue-gray. These belts are not simply stacked; they interlock. The rocks push forward into the sea; the sea climbs into the sky through soft atmospheric shifts. The three bands orchestrate a calm movement for the eye, both lateral along the shore and vertical through the registers of air.

The Seated Figure And The Measure Of Distance

At the far right a small figure sits on a simple bench or post, back turned, dotted dress and dark hat catching the light. This person is not a protagonist in the narrative sense; rather, the figure measures scale and anchors the viewing act within the painting. By placing the figure near the edge, Matisse aligns us with a fellow observer. The posture—resting, steady, attentive—mirrors the painting’s own ethic of looking. The spotted dress repeats the broken textures of scrub and rock, so the person belongs to the scene rather than puncturing it. A slim staff or cane doubles as a vertical accent that keeps the corner from dissolving into soft blues. With a few strokes he yields presence, distance, and mood.

Color Chords And The Temperature Of The Coast

The palette is tuned to a warm–cool opposition softened by coastal haze. The headland glows with ochres, honey, and burnt sienna, cooled in places by olive drabs where vegetation clings to soil. The sea begins as a breeze-blown teal near the shore, then deepens into a bluer register, with slate shadows sliding under the surface like submerged currents. The sky is a tempered mix of pale cerulean and pearl gray veils, its coolness moderated by thin warm undertones that peek through. Matisse avoids theatrical contrast. Instead he stages adjacency: warm ochre beside cooler olive, mid-blue beside deeper cobalt, pale sky beside a slightly warmer cloud. The result is a climate rather than a color stunt, the sensation of air and light distributed evenly across the day.

Brushwork And The Velocity Of Air

Matisse’s brush moves at the pace of weather. On land, strokes are short and tufted, climbing over rises and falling into pockets like wind lifting grass. Where rock breaks through, he scumbles thicker paint, letting warmth collect on ridges and cools sink into crevices. Over water, the brush lengthens into low, lateral drags, creating a surface that suggests both mass and movement. In the far sea he lays broader, quieter sweeps that stabilize the middle band. The sky receives the slowest touch: long, translucent veils that carry no hard edges and read as high air. The variety of handling keeps the registers distinct while letting them converse. You can almost hear the soft scrape of wind across stone and the hush of distant surf collapsing into the bay.

Space Without Illusionist Tricks

Depth in “Cap D’Antibes” is built from overlapping planes and tonal steps rather than from linear perspective. The foreground rocks overlap the middle shelf, which overlaps the darker water, which gives way to paler distant mountains. Values descend gently as distance increases; colors cool and soften; edges lose definition. The horizon line is held firmly but not with a ruler—its slight undulation insists on atmosphere and curvature of coast. The structure is modern because it keeps the canvas’s flatness in play. You feel the space because warm meets cool, near meets far, thick meets thin, not because of a vanishing point diagrammed into the scene.

The Headland As A Living Architecture

The rocky promontory is more than topography; it is architecture formed by rhythm. Sloped forms repeat across the foreground like shallow vaults, and their alternating sun and shadow become a visual meter. Darker seams where vegetation takes hold act like joints between stones. Matisse catches this architecture without chiseling it into geology. He is interested in the headland as a stage that bears light, not as a document for surveyors. This approach lets the coast become hospitable to the figure and to us. The land invites, it does not overawe.

The Sea As Emotional Regulator

Across Matisse’s work, a steady band of sea often acts as the painting’s emotional thermostat. Here the water cools the ochre heat, deepens the mood without darkening it, and introduces the calm horizontality that keeps the composition from tipping into a tumble of rocks. The pale silhouette of distant mountains flares briefly where land meets sky, then relaxes into the long arc of coastline. The water’s small islands and shelves puncture the surface with slow punctuation, so the eye does not race across the middle band but moves in clauses. It is a pedagogy of looking: see, pause, continue; repeat.

Weather, Season, And Time Of Day

The light suggests a clear, mild day—perhaps late morning or early afternoon, after haze has burned off but before the heat has thickened the air. Clouds are thin and stretched, more breathable film than towering mass. Shadows along the rocks are gentle; there is no raking drama. The palette’s moderation aligns with this seasonless temper. Matisse does not trap the view in the specifics of meteorology; he tunes it to a state that feels durable, the way a place often appears in memory—true to sensation rather than to fetishes of weather.

Pattern In Nature And The Nice-Period Eye

Even outdoors, Matisse’s Nice-period eye looks for pattern. The foreground’s brush tufts repeat with variation; the islands in the bay scatter in an informal grid; the distant mountains step in a measured cadence; the sky’s veils stack rhythmically. These patterns allow him to treat the landscape like an open-air interior. The sea band is the room’s back wall, the rocks are a carpet of ochre motifs, the sky is a translucent drape. This continuity between interior and exterior is central to his project in the early 1920s: to make an art where pattern and plane organize experience without suffocating it.

The Ethics Of Leisure

The tiny figure in hat and dotted dress is at ease, seated and looking. Nothing about the posture is theatrical. In Matisse’s Nice years, leisure is not idleness but a discipline of attention. The figure models this ethic. You sit, you look, you let the sea steady your breathing. The picture participates by withholding spectacle. It gives you a complete world with room to breathe: a wide view, a safe perch, and colors tuned for duration rather than for instant shock.

Drawing Inside Color And The Intelligence Of Omission

Matisse refuses to enumerate details where relationships suffice. Rocks are not counted; they are grouped by temperature and value. The islets are given as softened shapes whose edges melt into the water. The figure’s features are summed with a hat brim, a shoulder line, and a few dark notes for dress and shoe. The mountains are atmospheric envelopes, not chiselled ridges. These omissions are not shortcuts; they are decisions about where meaning lives. In this painting meaning resides in the broad relations—warm to cool, horizontal to undulant, near weathered mass to far vaporous chain.

Rhythm, Repetition, And Visual Music

The painting’s lasting pleasure is rhythmic. Foreground forms rise, crest, and fall; water planes darken and lighten; sky veils thicken and thin. Each zone keeps time, and their tempos interlock. The figure’s dotted dress echoes the pebble-like marks in the headland, while the hat’s dark oval rhymes with the small islets offshore. This web of affinities fosters a musical coherence. You can re-enter the painting at any point—the leftmost ridge, the central island, the figure’s hat—and the rhythm will carry you forward and back without rupture.

Material Presence And The Sense Of Place

Despite its economy, the picture is tactile. You feel the tooth of dry grass in the quick ochre strokes; you sense the slick, heavier drag of paint where shadow collects; you perceive the water’s skin in the horizontal brushing that lays pigment almost like glaze. These touches anchor the scene in the body. It is not postcard prettiness; it is a place you could walk, sit, and breathe. Matisse uses the material truth of paint to transmit the material truth of coast.

Comparisons Within The Southern Landscapes

Placed beside “Paysage du Midi” or “In the Woods,” this view of Cap d’Antibes occupies the open-water end of Matisse’s southern spectrum. Where the grove paintings build vaulted interiors from trees, this canvas broadens into weather and distance. Yet the methods are the same: clear bands of space, a restricted but resonant palette, and the small presence of a figure as a humane metronome. Within his 1922 production, it reads as a hinge between interior poise and maritime expanse, proof that his quiet architecture of color and line could scale to the horizon.

The Viewer’s Path And The Loop Of Attention

The painting choreographs a dependable loop for the eye. You enter at the warm foreground ridge, ride its curve to the center, step to the islands, drift across the deep middle water, rise to the pale mountains and sky, then return along the coast to the far right where the small figure waits. From there the bench’s vertical brings you back down to the warm rocks. Each circuit is unhurried and clear. The loop is more than a compositional trick; it is a way to impart the experience of standing on a headland and letting the view fill you again and again.

Emotional Weather And The Poise Of Calm

The emotional register is composed and bracing. The warmth of the rocks promises comfort; the breadth of the sea promises clarity. Nothing is sentimental or severe. This poise is what gives the painting modern durability. It offers an image of attention that is sustainable, a visual climate one can inhabit without fatigue. In an age of spectacle, it models measured seeing, the kind that replenishes rather than depletes.

Conclusion: A Promontory Of Light, Rhythm, And Rest

“Cap D’Antibes” condenses Matisse’s mature aims into a coastal chord. Three bands—rock, water, sky—hold a steady rhythm; a single figure measures scale and models attention; color breathes between warm ochre and tempered blue; brushwork moves at the speed of air. The view is specific yet archetypal, a promontory anyone who has loved a coastline will recognize. Matisse does not dazzle with detail; he persuades with relations. The result is a painting that continues to feel like a place to stand and breathe, a promontory of light, rhythm, and rest.