Image source: wikiart.org

Historical Context And The Poetics Of The Nice Period

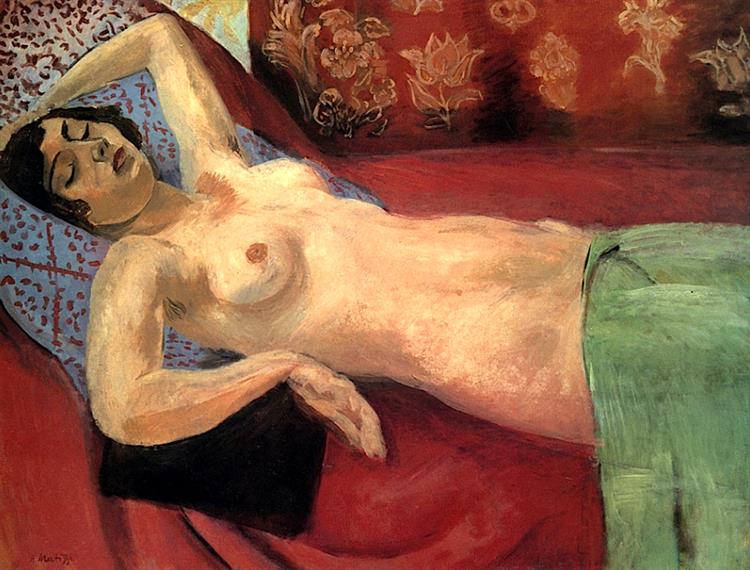

Henri Matisse painted “Nude with a Green Shawl” in 1922, in the midst of his Nice period when he transformed modest hotel rooms into theaters of patterned textiles, filtered light, and serene human presence. After the shock of Fauvism and the tumult of the 1910s, he sought clarity rather than clamor, cultivating an art of calm intensity in which a few tuned relationships—between color fields, contours, and textures—could hold an entire world. The odalisque theme served him as a flexible stage: a reclining body, a bed or divan clothed in fabrics, a sprinkling of ornamental cues, and a bath of Southern light. This painting shows the method at full strength. The model lies diagonally across the canvas, her torso luminous against a deep red ground, a cool green shawl at the lower right sealing the chord. The scene proposes a modern ideal of repose, not spectacle, in which sensuality is borne by color and rhythm rather than by narrative devices.

Composition As A Diagonal Of Rest

The composition is engineered around a powerful diagonal from the upper left, where the model’s raised arm travels across the headboard zone, to the lower right, where the green shawl pools at the hip. This diagonal is countered by a parallel red flow of bedding, creating a soft V that cradles the figure. Matisse compresses space so that body and fabric share one shallow plane; there is little perspectival scaffolding beyond the suggestion of a pillow and upholstered background. The closeness produces intimacy without intrusion. The viewer is invited to read the passages of the body as they move along the diagonal—shoulder, breast, ribcage, abdomen, hip—each articulated by temperature shifts and by edges that thicken or thin in response to light.

The Body As A Field Of Tuned Temperatures

Matisse renders the nude in a key of pale apricots, cool pinks, and pearly grays, calibrated so that flesh itself becomes a luminous field. Rather than construct muscular relief through heavy modeling, he uses temperature to turn form. A cool gray at the edge of the arm sets it off from the pillow; a warmer cream across the sternum brings the chest forward; a diluted rose helps the abdomen turn away. The body is not a chunk of sculpture planted on fabric; it is a plane that slips gently into its surroundings. The face, tipped back in sleep, is simplified to a few decisive notes—dark hair against a cooler forehead, the gentle crescent of closed eyelid, the small pool of shadow under the chin. The hand at the lower center is drawn with elastic economy and becomes a hinge in the composition, both resting and quietly directional, guiding the gaze toward the green shawl.

Color Chords And The Drama Of Warm Against Cool

The painting’s emotional engine is a triad of color families: the enveloping reds of the bedding, the pearly warm-cool of flesh, and the fresh, grassy green of the shawl. Matisse sustains the reds across several registers—terra cotta, crimson, wine—so that the ground breathes rather than clots. The red range announces warmth and privacy; it reads as the temperature of the room itself. Against this, flesh takes on a slightly higher light and a subtler spectrum, so the figure glows without being outlined. The green at the hip completes the chord. Because green is complementary to red, it acts like a tonic that settles the eye after the long travel of warm tones. It also is strategically placed at the terminus of the diagonal, pinning the composition and preventing visual slide. The shawl’s hue is not acidic or decorative; it is a structural color that steadies the entire harmony.

Ornament As Atmosphere Rather Than Distraction

Behind the head a panel of patterned textile introduces a constellation of blue dots on a pale field; above and beyond it an upholstered red backrest carries floral motifs in a slightly darker key. These ornaments are modest but essential. They keep the upper half of the painting from becoming a monotone, and they plant the body within a tactile setting that reads as lived-in rather than theatrical. Matisse was always careful that ornament do structural work. Here pattern helps separate planes, articulates zones of temperature, and supplies a calm counterpoint to the smoothness of skin. Because the marks are abbreviated—more suggestion than inventory—ornament remains atmosphere rather than narrative anecdote.

Drawing Inside The Paint

Matisse’s drawing is not a contour wrapped around color; it is a behavior of the brush inside color. The forearm is declared by a single, swelling stroke that tapers near the wrist, the curve of the torso by a meeting of warm and cool bands, the clavicle by a brief, calligraphic accent. Where an edge would become brittle, he lets it blur slightly so the air can pass between forms. The breast, often a test of awkwardness in less deft hands, is presented with just enough modeling to register weight and anatomy without stiffness. The small tilt of the head is calibrated by the hairline’s curve and a faint shadow pooling at the neck’s hollow. Every line is economical; every omission is intelligent. The drawing’s authority allows the color to remain soft without losing clarity.

Light As A Soft Envelope

The light source is implied rather than diagrammed. It enters from above and to the left, laying a warm wash across the upper torso and a cooler sheen along the forearm and hip. There are no theatrical shadows or raking beams. Light is a condition, not an event. This matters because it keeps the painting open to sustained viewing. Instead of staging a climactic moment, Matisse offers a continuous air in which the eye can linger. Highlights are modest—on the shoulder’s crest, on the forehead’s arc—confirming volume while preserving the painting’s overall hush.

The Ethics Of Repose

Matisse’s nude is neither coy nor displayed. The closed eyes, the slack mouth, the unguarded arm above the head all state sleep rather than performance. Because the composition’s energy is carried by color and diagonal rhythm, the painting does not rely on voyeuristic devices to claim attention. The body is at ease in its own time, and the viewer is invited to adopt that tempo. This ethics of repose was central to Matisse’s Nice period: he sought to create rooms and images where attention could slow without collapsing, where pleasure and measure would support each other.

The Green Shawl As A Sign And A Seal

The shawl is small in area but large in consequence. It anchors the composition where warm skin meets warm ground, delivering the cooling complement that crystallizes the scene. Its material is signaled by a thicker application at the edge and a soft interior modeling that hints at folds without enumerating them. Symbolically it is a gentle cover—modesty as color, not as concealment. Formally it seals the phrase that the body composes, a terminal note that lets the viewer’s eye rest and return.

Space Constructed By Contact And Overlap

Although the space is shallow, Matisse clarifies it with small, precise contacts. The dark cushion catches the weight of the head and sets a value contrast that pushes the face forward. The patterned panel meets the backrest along a slanted seam that echoes the body’s diagonal. The shawl climbs slightly over the hip and then falls away, confirming the volume without disturbing the plane. These overlaps stitch the picture together. They also make tactility vivid; one can feel the difference between plush and cotton, between skin and woven nap, through the way edges meet.

Rhythm And The Viewer’s Path

The picture choreographs a path that is as physical as it is visual. The viewer enters at the luminous torso, glides along the arm to the hand, slips into the green shawl, returns along the curve of the abdomen to the breast, and climbs to the face and the raised arm. The patterned panel and the floral motifs attract quick glances that bounce the gaze back to the body. Each circuit is unhurried and complete, like a breath. The rhythm depends on alternation—warm, cool, warm; soft, patterned, soft—and on Matisse’s sure sense of when to tighten a contour and when to loosen it.

Comparisons Within Matisse’s Odalisques

Compared with other odalisque canvases of the early 1920s that overflow with props, screens, and instruments, “Nude with a Green Shawl” is distilled. There is no musical device, no vase, no window; the drama is carried by the meeting of skin and color field. In this restraint one can feel the direction Matisse was heading: toward larger planes, clearer chords, and a reliance on the viewer’s sensitivity to temperature and interval. Yet the painting remains sensuous. The red ground is sumptuous; the patterns whisper of craft; the green is fresh as air from a garden door. It is a hinge work, poised between lush interior and the later clarity of his 1930s drawings and, further on, the cut-outs.

Material Presence And The Pleasure Of Paint

The canvas is a record of chosen pressures. The reds are brushed in with varying density so that some areas glow and others absorb light. The flesh passages are glazed thinly enough to let underlayers influence temperature, thickened just at the crests to catch a soft shine. The shawl is handled with a slightly heavier touch that lets pigment sit as fabric might. Paint itself becomes a subject—the pleasure of the medium aligned to the pleasure of seeing. This material frankness keeps the image from prettiness. It belongs to the hand and to the day’s light, not to fantasy alone.

Psychological Weather And The Quiet Face

The face is one of Matisse’s quiet triumphs here. With a handful of strokes he locates a personality that is at rest but not emptied. The mouth is relaxed but defined; the cheek carries enough color to feel warm; the dark hair frames the head with authority. Many painters make sleeping faces anonymous; Matisse preserves the sense that this is a particular person whose features have been simplified in sleep but not erased. That balance—between individual presence and pictorial economy—deepens the painting’s calm.

The Sensual As Structural

Much writing on Matisse’s odalisques revolves around sensuality, but in this canvas sensual response derives from structural clarity. The long diagonal encourages the body to be read as a phrase, the color chord turns temperature into feeling, and the patterned field measures the smoothness of skin. Sensuality is an outcome of looking rather than a subject forced by anecdote. The painting’s generosity lies in how it lets perception do the work of pleasure.

The Legacy Of The Work

“Nude with a Green Shawl” resonates today because it proposes a sustainable way to look at the human figure. It removes drama without denying feeling, and it trades virtuoso finish for the intimacy of tuned decisions. Designers can learn from its chromatic architecture—a dominant warm ground steadied by a cool countercolor, with a central neutral field for the protagonist. Painters can study the intelligence of its omissions and the confidence of its edges. Viewers can return to it to practice a slower attention that finds richness in small temperature changes and quiet intervals.

The Viewer’s Experience Of Time

Spending time with the picture lengthens the senses. At first the red announces itself; then the flesh’s modulations come forward; finally the green reveals how necessary it is. With each pass the body’s weight becomes more convincing and the room’s air clearer. The painting’s temporality is cyclical, not linear. One does not advance through a story; one breathes with a set of relations that stay vivid as long as one is willing to look.

Conclusion: A Calm Chord Held In The Hand

“Nude with a Green Shawl” condenses the Nice period’s values into a single, lucid arrangement. A diagonal of rest, a chord of red, pearl, and green, a few patterned murmurs, and a body painted with respect for its weight and warmth are enough to make a world. Matisse’s art here is not the art of addition but of tuning. He knows exactly how much to state and how much to let the air supply. The result is an image that does not shout for attention but sustains it—a calm chord held in the hand, still resonant a century later.