Image source: wikiart.org

Historical Context And A Return To The Open Air

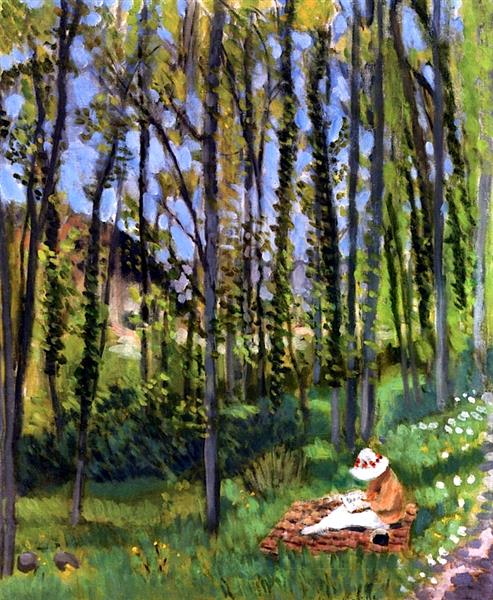

Henri Matisse painted “In the Woods” in 1922, during his Nice years when he alternated between luminous interiors and excursions outside to test how his mature language of color and contour behaved in natural light. The war decade had pushed many artists toward severity, yet Matisse turned to clarity and calm. In this woodland scene he adapts the serenity of his domestic rooms to an outdoor space whose architecture is made of trunks, saplings, and slender bands of sky. The painting captures a moment of poised leisure—a figure seated on a low woven mat at the forest’s edge—while staging a broader meditation on how rhythm, pattern, and air can transform a grove into a living studio.

Composition As A Vertical Orchestra

The composition is governed by a forest of thin verticals. Trunks and tall saplings rise rhythmically from the lower edge to the top, their spacing slightly irregular so the eye never falls into mechanical repetition. This columnar screen divides the picture into narrow lanes of greens and blues, creating a measured tempo that organizes the whole. Against this vertical orchestra Matisse sets two moderating diagonals: the slant of the meadow path at right and the gentle rise of the ground from left to right. These obliques keep the verticals from locking the space, opening a route for the viewer’s gaze into and across the woodland.

Trees As Architecture And Pattern

Matisse treats the trees as a flexible framework, much as he treats wallpaper and lattice floors in his interiors. Ivy twines up the shafts like decorative motifs, foliage clusters into small leaf-tiles, and intervals of sky appear as patterned windows within the screen of trunks. This translation of nature into pattern is not an abstraction imposed from without; it is an answer to what the grove already offers. The forest is a ready-made colonnade, its repetition and variation lending the scene an architectural dignity without diminishing its wildness. The result is a space that reads as both organic and designed.

The Seated Figure As Lyrical Accent

At the lower right a figure in pale dress and warm outer layer reclines on a woven mat, perhaps sketching, writing, or simply resting. A white hat with a ring of red blossoms becomes a small beacon in the abundant green. The body’s compact triangle gives the composition a human scale and a point of rest. Matisse declines portrait detail; the person is a presence rather than a protagonist, a measure of the forest’s height and a sign of the unhurried attention that defines the painting’s mood. The figure’s warm notes also complete the palette, bridging earth and leaf with human color.

Color Chords And The Temperature Of Spring

The palette is tuned to spring: fresh greens in multiple keys, cool blue-violets in the vertical gaps of distant air, and warm ochres in the exposed earth and path. The greens range from sap to olive to emerald, laid next to one another so that the eye senses variety without losing unity. The small, strategic reds in the hat and the few dandelion dots near the path are like sparks struck from the cool chord; they intensify the surrounding greens by contrast. Shadows are colored rather than black, so that even the darker forms remain breathable and luminous.

Light As A Living Sieve

Sunlight in a wood rarely arrives in beams; it is filtered through a million leaves. Matisse records that sieve with flickering touches along trunks and across the meadow floor. Where the canopy thins, the sky opens into cerulean patches; where it thickens, the greens cool and deepen. The light’s distribution isn’t theatrical. Instead it is a continuous field, a tissue of half-tones and glimmers that holds the space together. The viewer senses a day that is bright but tempered, maybe early afternoon when the woods hum quietly and the air is cool under the trees.

Brushwork And The Velocity Of Seeing

The brush moves at several speeds. Trunks are declared with single, elastic strokes that swell and taper like calligraphy. Ivy and leafage are rendered in quick, comma-like touches that collect into soft clusters. The meadow is scumbled with short strokes, letting flashes of ground color peep through so the grass seems to vibrate. The sky is laid thin and even, a smooth counter to the busy greens. Nothing is fussed over; the paint records decisions swiftly. The surface thus mirrors the experience of walking and looking in a wood, where perception hops from one incident to the next while remaining aware of the whole.

Space Built By Overlap And Tonal Steps

Depth in “In the Woods” arises less from linear perspective than from overlapping silhouettes and carefully graded values. Trunks in the foreground are darker and more defined; those farther back thin and cool into bluish grays. The meadow transitions from bright, textured strokes up close to softer, more uniform planes in the distance. The path’s ribbon of pale earth narrows as it recedes, but even that cue is modest. The space is shallow enough to hold together as a patterned surface and deep enough to be entered imaginatively.

The Path And The Promise Of Movement

At the right edge a slender path threads upward through grasses dotted with white flowers. This path is both narrative and compositional. It suggests gentle movement—the figure might have come along it to rest here—and it offers the viewer a route into the scene. Its pale, warm color breaks the green field, gives the eye a place to pause, and reaffirms the diagonal counterpoint that keeps the verticals lively. The little constellation of white blossoms along its edge is a tender register of season and scale.

Rhythm, Repetition, And Visual Music

The painting’s pleasure lies in its rhythms. Trunks repeat like musical bars; leaf clusters splay and contract like phrases; the figure, mat, and path punctuate the beat with rests. Matisse is a master at varying repetition. No two verticals are exactly alike; they lean, thicken, and carry different amounts of foliage. These micro-variations keep the eye awake while the macro-rhythm maintains calm. One experiences the wood as a kind of score—orderly enough to be legible, supple enough to feel alive.

The Intelligence Of Omission

Matisse leaves out what would clutter the harmony. There is no botanical accounting of species, no bark texture parsed into detail, no explicit description of the figure’s features. Instead, he gives just enough sign to let forms cohere: a dark seam where a trunk overlaps another, a pale edge that turns a boulder, a red dot that resolves as a flower. These omissions clear the air so that color and spacing—the painting’s real subject—can breathe.

Dialogue With The Artist’s Interiors

The woodland scene converses with Matisse’s interiors from the same years. The tree trunks function like the uprights of window frames and screens; the interleaving of sky and foliage behaves like patterned wallpaper; the meadow acts as a carpet whose motifs are made by light. Even the seated figure echoes the odalisques indoors, transposed here into a modern plein-air idiom. Recognizing this continuity deepens the canvas: it is not a detour from his concerns but a demonstration that his language of pattern and poise can thrive under open sky.

Season, Weather, And Emotional Tone

Everything points to a mild season—perhaps late spring when leaves are fresh, trunks still legible, and meadows are strewn with first blooms. The emotional tone matches the weather: alert serenity. The cool blues prevent the greens from becoming sugary, while the reds and ochres prevent a slide into chill. The figure’s rest and the woods’ vertical lift combine into a mood both contemplative and quietly buoyant. The painting neither dramatizes solitude nor stages sociability; it simply offers a steady place where looking can be complete.

Material Presence And Tactile Cues

Although the image is airy, material cues abound. The woven mat reads as rough by the broken strokes across its surface; the path looks compacted by soft, horizontal touches; the ivy’s darker notes imply a slight tackiness against bark; the boulders at the lower left turn with cool violets that suggest granite’s skin. Such details remain subordinate to the overall rhythm, but they anchor the scene in lived sensation. One can imagine the weight of sitting, the coolness of shade, the thin breeze that moves the leaves high above.

The Viewer’s Path And The Experience Of Time

The eye’s itinerary begins at the figure’s white hat, leaps to the mat’s ochre, climbs a nearby trunk, wanders through the lattice of trees, and emerges at the path with its string of flowers. This loop can be repeated indefinitely, each march revealing a new interval of color or a slightly different alignment of branches. Time dilates. The painting invites the same kind of attention the figure seems to practice: lingering, unpressured, curious.

Comparisons Within The Artist’s Landscapes

“In the Woods” sits alongside other southern landscapes from the early 1920s in which Matisse sought a balance between description and patterned clarity. Compared with the more open grove of “Paysage du Midi,” this canvas is denser, more vertical, and keyed slightly cooler. Where “Paysage du Midi” builds a nave of olive trunks under pale light, “In the Woods” compacts the architecture and quickens the rhythm, raising the verticals like organ pipes. Both, however, rely on the same economy: a restricted chord of greens moderated by blues and ochres, a human figure treated as an accent, and brushwork that remains brisk enough to keep air circulating.

What The Painting Teaches About Looking

The canvas proposes a method of seeing that is patient and structural. First, register the frame of verticals. Second, feel how diagonals and small horizontals coax the eye to travel. Third, allow color temperatures to orient you: cooler in the depths, warmer on the ground, quick red sparks as guides. Finally, return to the figure and notice how human scale calibrates the forest’s reach. Practicing this method in front of the painting changes how one subsequently looks at actual woods; patterns stand out, and the mind learns to assemble space from intervals rather than from measurements.

Legacy And Contemporary Resonance

The enduring appeal of “In the Woods” lies in its sustainable pleasure. It does not rely on spectacle; it relies on tuned relations—between tree and sky, green and blue, pause and motion, person and place. In a visual culture crowded with extremes, this canvas offers an ethics of attention: to attend is to belong. Designers can learn from its distribution of accents, painters from its colored shadows, and general viewers from its calm. The grove becomes not a retreat from life but an image of life practiced at a bearable tempo.

Conclusion: A Studio Made Of Trees

“In the Woods” demonstrates how Matisse could transplant the logic of his interiors into nature without losing immediacy. Vertical trunks act as columns, sky as patterned fabric, meadow as carpet; within this architecture a single person sits, unhurried, receptive. The color is springlike and measured, the drawing calligraphic, the light a gentle sieve. The painting lasts in the mind because it turns a commonplace scene—trees, path, seated figure—into a clarified experience of breathing with the world. It is a studio made of trees, a room without walls where looking itself becomes the work.