Image source: wikiart.org

Historical Context And The Nice Interior

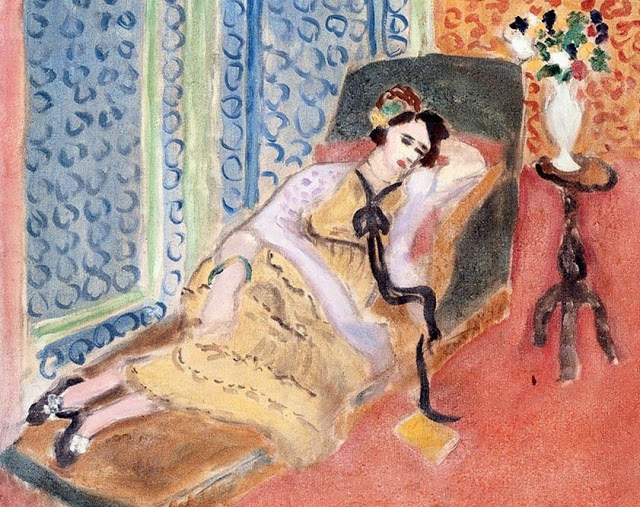

Henri Matisse painted “Young Woman on a Divan. Black Ribbon” in 1922, at the heart of his Nice period when interiors, patterned textiles, and unhurried sitters became a sustained laboratory for color and form. After the turbulence of the 1910s he turned toward rooms filled with gentle light, seeking a pictorial language that could be at once clear, sensuous, and calm. The Nice studios allowed him to orchestrate fabrics, flowers, screens, and furniture as if they were instruments in a chamber ensemble. This painting shows the method in full: a reclining model, a chaise that stretches diagonally across the composition, patterned walls and draperies, and a few eloquent objects—a small table with a white vase, a closed book on the floor—arranged to make a complete world out of measured relationships.

Composition As A Diagonal Stage

The composition is anchored by the chaise longue, which runs from lower left to mid-right like a quiet arrow. The figure reclines along that diagonal, her head cushioned on her right arm, her left hand falling toward the dress’s dark bow. Matisse counters this oblique sweep with a set of verticals: the two panels of blue patterned drapery at the left and the narrow wall reveal at the far right. A small pedestal table with splayed legs interrupts the upper right corner, carrying a white vase whose bright mass steadies the upper register. The floor is a coral-pink field that rises just enough to compress space into a shallow, legible stage. Every element is placed to guide the eye in a smooth loop—up the chaise and arm to the face, across to the vase, down through the table legs to the book, and back along the chaise to the figure’s shoes.

The Black Ribbon As Visual Theme

The title’s “Black Ribbon” is not merely an accessory; it is the graphic theme that stitches the painting together. Tied at the throat, it falls in a long, undulant line over the yellow dress, emphasizing the torso’s gentle curve and clarifying the pose without heavy modeling. Its inky note is echoed in the dark hair, the bow at the waist, the shoes, the table’s tripod legs, and the crisp outline of the chaise. Matisse frequently used a single dark arabesque to choreograph movement across a bright field; here the ribbon is the conductor’s baton, setting tempo for the eye and preventing the pastel chord from dissolving into sweetness.

Color Chords And The Temperature Of Calm

The palette is a lucid chord of coral, lemon-yellow, blue, sea-green, and warm creams held in equilibrium by small accents of black. The coral floor warms the lower half of the canvas and tilts the space toward us. The blue draperies cool the left side with a soft, watery rhythm, while the greenish gray of the chaise keeps the center grounded. The dress glows as a middle key between floor and curtains—sunlit but not loud. Whites appear strategically: as lace at the sleeve, as the crisp ceramic of the vase, and as milky highlights within the patterned curtains. The balance of warm and cool sustains the painting’s poise. Instead of contrast for its own sake, Matisse prefers adjacency—close variations that create atmosphere, a method consistent with the Mediterranean light that filters evenly through fabric rather than striking with theatrical glare.

Pattern And Ornament As Architectural Framework

Pattern is the architecture of the room. The blue curtains at left are inscribed with looping motifs that read as a musical counterpoint to the dress’s stitched ornament and to the arabesque of the ribbon. Behind the chaise, a field of coral latticework or wallpaper rises like a warm screen, its small repeating shapes knitting the background into a breathable surface. Ornament here does not decorate after the fact; it builds the space and sets rhythm. Because pattern extends across large planes—curtains, wall, floor—Matisse can keep the figure simplified without sacrificing visual richness. The model is thus integrated into a patterned world rather than staged against it.

The Figure And The Poise Of Repose

The young woman’s pose is a study in unforced elegance. Her weight falls naturally along the chaise, hip slightly forward, knees relaxed, feet pointed modestly toward the floor. The head tips toward the viewer with a trace of alertness; the expression is attentive rather than theatrical. The face is modeled economically with warm and cool notes that turn gently around brow and cheekbone. Hair is rendered as dark, soft masses that frame the face while rhyming with the ribbon. A green bracelet at the wrist and a floral adornment in the hair provide small color bridges between dress, curtains, and wall. Matisse’s ethic of ease is evident: the figure is dignified not by a grand pose but by the right cadence within the room’s geometry.

Brushwork And The Breath Of The Room

The paint handling is supple and aerated. Across the coral floor Matisse allows thin veils to show the ground, creating a sense of light absorbed by textile. The curtain patterns are brushed with quick, looping strokes that enliven the surface without becoming fussy. The chaise is laid in with broader, denser passages that establish a felt solidity where the figure rests. On the dress, a sequence of broken strokes suggests stitched seams and soft folds; the modeling never drags the form toward heaviness. The white vase is delivered with a few decisive sweeps, its brightness catching and reflecting the room’s color. The brushwork maintains momentum across the canvas, letting the surface breathe while giving each object a distinct tactile register.

Light As A Soft Envelope

The light is domestic and filtered, more veil than spotlight. It enters from the left—suggested by the luminous curtains—and spreads evenly across the couch and figure. Shadows are cool and thin, more changes of temperature than plunges into darkness. On the dress, light pools into small warm gradations; on the face it lifts the forehead and cheek while leaving the eye sockets soft. The vase receives the highest value, a white that anchors the top right corner and reaffirms the light’s origin. This even illumination is essential to Matisse’s project: it allows color to hold the emotional register without being bullied by dramatic shadow.

Space Organized By Planes, Not By Tricks

Traditional perspective is muted. Space arises from stacked planes—the coral floor, the chaise, the patterned wall, the curtains—whose relationships are clarified by color and overlap. The chaise’s diagonal gives the composition its depth cue; the book on the floor, slightly skewed, acts as a small perspectival hinge near the viewer. The result is a shallow, legible space that keeps the entire scene within reach. This shallowness is not a limitation; it is a choice that allows decorative order and human presence to share a single pictorial plane.

Objects As Quiet Witnesses

Two objects punctuate the composition: the small book on the floor and the white vase of flowers on the table. The book’s mustard cover introduces a compact echo of the dress and suggests paused reading, a narrative thread held in reserve. The vase, crisp and pale, elevates the upper corner and adds a vertical counterform to the chaise’s long slope. Its stems and blossoms repeat the curtain’s looping rhythm in miniature. These items are not mere props; they are witnesses of a life in progress—a moment of rest within a day that includes reading, arranging flowers, and attending to the room.

The Model’s Dress And The Language Of Fabric

The yellow dress functions as both color field and map of movement. Stitched or painted dots indicate seams that trace the body’s curves, creating a quiet drawing across the fabric. A pale lilac shawl slips over the shoulder, cool against the warmth of the yellow and coral, and registers the texture of lace with abbreviated zigzags. The black bow at the collar anchors the face and initiates the ribbon’s long descent. By giving the model a modern garment rather than an exotic costume, Matisse affirms the contemporary interior: this is not a harem fantasy but a real room in which pattern and color express modern grace.

Rhythm, Repetition, And Visual Music

Repetition organizes the painting like a score. Curved forms recur: the ribbon’s S-shapes, the looped curtain motifs, the handles of the vase, the rounded pillow edge beneath the head. Straight edges—the book, chaise frame, table top—counter these curves without disrupting them. Color repetitions knit the scene: the yellow of the dress returns in the book; the blue of the curtains whispers in the cool shadows of the chaise; the coral of the wall answers the floor. These repetitions create a rhythm that the viewer feels as much as sees, a measured cadence that supports the mood of suspended time.

Drawing Inside Color And The Intelligence Of Omission

Matisse’s drawing is carried by color boundaries rather than by firm outlines. Where line appears—around the profile, along the ribbon, at the chaise’s edge—it is elastic and responsive. Details are withheld whenever they would distract. The flowers in the vase are compact notes of cream and dark; the book’s pages are a single plane; the shoes are simplified to silhouettes. These omissions keep attention on the painting’s main truth: how a person and a room can be made eloquent through tuned relationships of hue, tone, and interval.

Emotional Weather And The Poise Of Rest

The emotional temperature is balanced between languor and alertness. The reclining posture and the soft bed of color suggest ease; the clear gaze and the graphic ribbon add a touch of formality. Nothing is feverish. Instead, the scene proposes a modern ideal of rest: attention slowed but not dulled, a body at ease within an environment arranged for calm. Viewers often experience this as a deep breath. The painting does not shout; it steadies.

Dialogues Within Matisse’s Oeuvre

“Young Woman on a Divan. Black Ribbon” converses with Matisse’s wider Nice interiors and with earlier experiments. It shares with the odalisque canvases a reclining figure and fields of pattern, yet it tempers the exoticism with modern dress and a pared set of objects. Compared with the high-key explosions of 1905, the palette here is moderated and harmonious; compared with the radical simplifications of the 1930s drawings and late cut-outs, it remains lush but controlled. The painting therefore stands at a hinge: generous with ornament yet already committed to clarity.

The Viewer’s Path And The Experience Of Time

The picture choreographs a specific route for the eye. You begin at the black shoes, travel up the diagonal of the legs to the sash and bow, pause at the face, drift to the vase in the right corner, drop down the tripod to the yellow book, and return along the chaise’s edge. Each circuit takes only seconds, but the room’s atmosphere expands time; the loop invites repetition. The painting becomes an instrument for quiet attention—its reward increases with duration.

Legacy And Contemporary Resonance

The canvas remains resonant because it models how a small number of tuned elements can generate a full, habitable world. It suggests a mode of interior life that is not overloaded with things but richly patterned with attention. In an era of visual noise, the measured chord of coral, blue, yellow, and cream feels newly generous. The black ribbon—a simple stroke—shows how a single graphic element can unify a scene without coercing it. Designers, painters, and general viewers alike can learn from its economy and grace.

Conclusion: A Room Tuned To A Single Ribbon

“Young Woman on a Divan. Black Ribbon” distills the Nice period’s promise: a serene room where figure, pattern, and light sustain each other. The diagonal chaise, the cooling curtains, the coral field, the white vase, the modest book, and the supple black ribbon collaborate to form a composition that breathes. The model is neither idol nor anecdote; she is the precise center of a chord. Through careful color and lucid drawing, Matisse turns rest into form and form into lasting calm.