Image source: wikiart.org

Historical Context And The Return Of The Goldfish Motif

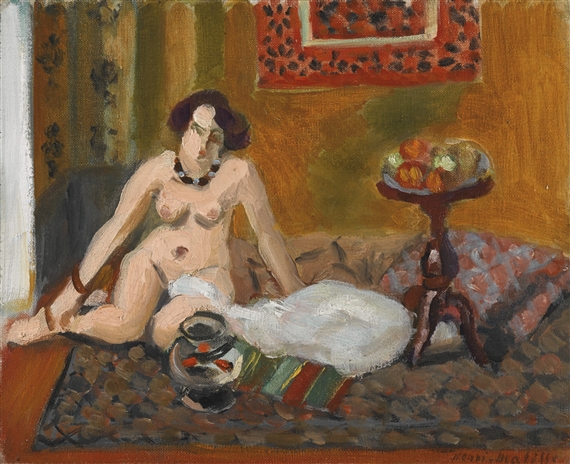

Henri Matisse painted “Nude with Goldfish” in 1922, during the Nice period when his studio became a theater of patterned textiles, low furniture, and luminous, measured color. The odalisque theme—women at ease among cushions, rugs, and screens—offered him a flexible stage for testing how figure, ornament, and light could coexist without hierarchy. The goldfish had already appeared in his work as early as 1912, when he made a series of paintings in Issy-les-Moulineaux that centered on a cylindrical aquarium. A decade later, the motif returns inside a denser interior, placed near a seated nude whose body, fabrics, and surrounding objects form a single chord. The date matters because it shows a mature painter using restraint rather than shock. Instead of the blazing Fauve palette, he orchestrates warm reds, tawny ochres, and deep greens into a controlled harmony capable of carrying atmosphere and mood.

Composition As A Horizontal Stage

The painting is organized as a horizontal stage spanning from a white curtain or wall on the far left to a pedestal table at right, with the nude occupying the center foreground. She sits on a patterned carpet or coverlet that rises steeply toward the back wall, converting floor into an ornamental plane. A large white cushion lies near her thigh and a striped cushion leans like a small ramp toward the pot of goldfish. Above, a rectangular textile hangs on the wall, rhyming with the patterned ground below and bracketing the figure within a box of color. At the far right, a dark wooden stand holds a glass bowl of fruit, its circular top echoing the round mouth of the fish vessel at the left. This left–right echo sets the tempo: two circular “altars” to life—swimming fish and gathered fruit—flank a living body at rest.

The Figure As Anchor And Rhythm

The nude is drawn with broad, decisive contours. Her torso tilts diagonally, one arm stretched along the floor, the other bent behind her for support. A simple beaded necklace rings the neck, repeating the shape of the fruit and the fish while punctuating the skin’s warm tone. She wears a bracelet that flashes a small accent on the wrist. The head is turned down slightly, allowing the hair to fall in dark arcs that frame the face. There is no elaborate anatomy; volume is declared by gentle tonal steps and by edges that swell or taper with the brush’s pressure. The figure supplies both weight and cadence. Her limbs mark intervals across the patterned carpet, breaking the surface into readable zones and keeping the eye from slipping quickly across the ornament.

Color Chords And Temperature Balance

The palette is a carefully tuned chord of brick red, rusty orange, tawny ochre, olive green, smoky violet, and milky white. The carpet carries a dark, cool pattern that counterweights the warm wall and the deep red of the hanging textile. The white cushion and the light passages on the figure’s flesh introduce areas of rest within the dense field. The goldfish themselves supply small, saturated sparks of orange that repeat in the wall textile and in the fruit, tying the canvas together chromatically. Rather than driving toward maximal contrast, Matisse prefers adjacency: warm on warm, cool within cool, a sequence of close differences that produces atmosphere rather than noise. The effect is intimate and sonorous, like a chamber ensemble where each instrument is clearly placed.

The Goldfish As Motif And Idea

The pot at the lower left is not a laboratory aquarium but a dark, rounded vessel whose wide mouth presents the water almost level with the rim. A few red fish float as crisp signs against the gray water. In earlier goldfish paintings the container was more architectural, a cylinder on a table; here it is more domestic, nearly a jar, embedded among cushions as if it belonged to the same world of textiles and rest. The goldfish carry multiple roles. They are small beings in continuous motion, a living counterpoint to the stillness of the nude. They add a note of cool liquidity to a room saturated with fabric. They also act as mirrors of attention. In 1912 Matisse spoke of watching goldfish as a model for concentrated seeing; by placing them beside the figure, he proposes that quiet looking—whether at fish, fruit, or a person—is itself a subject for painting.

Fruit Stand And The Theme Of Sustenance

Across from the fish jar stands the pedestal with a shallow glass bowl of fruit. Its vertical stem and round top introduce a sculptural shape into a world of soft objects. The fruit glow like muted jewels—yellow-green, red, and orange—echoing the fish while shifting the metaphor from water to nourishment. The pedestal’s curved legs and turned shaft align with the painting’s broader rhythm of arcs and loops. Together, the fish and fruit stage a conversation between two forms of life-keeping: water and food. They also formalize the left–right balance of the composition, as if the room were arranged to keep the central body centered not only by cushion and carpet but by offerings at either side.

Brushwork And The Pulse Of The Room

The paint handling is frank and tactile. Matisse lays down color in thick, confident strokes over a ground that still breathes at the edges. The carpet’s pattern is built from brisk, repeated marks rather than from meticulous motifs. The wall textile is blocked in with rectangles of red, black, and gray that read from a distance as a woven design. The white cushion is sculpted with creamy impasto, its edges blending into the carpet in places so that fabric seems to absorb light. The nude’s flesh is painted with a mix of warm ochres and cool notes in shadow, the brushwork looser at the limbs and more concentrated around the face and torso where clarity matters most. This distribution of touch produces a pulse across the canvas. We feel the slow thrum of a room in the heat of day, everything slightly drowsy yet precise.

Space Built By Overlap And Pattern

Perspective is minimal. Depth arises from overlapping shapes: the cushion over the carpet, the fish jar set partly onto the cushion, the fruit stand overlapping the patterned ground, the hanging textile overlapping the wall. The back wall narrows the stage by rising quickly from the foreground, pressing the scene into a shallow box that keeps all elements near the surface. Shallow space is crucial to the painting’s thesis. It allows figure and objects to operate as patterns in a single plane, making kin of things normally separated—skin and cloth, glass and water, thread and fish.

Ornament As Structure Rather Than Accessory

In Matisse’s Nice interiors, ornament does the heavy lifting of structure. Here the carpet’s geometry organizes the lower half of the painting, providing a field against which limbs, cushions, and vessels can declare their edges. The wall textile stabilizes the upper half, preventing the warm wall from becoming monotonous and locking the figure into a coherent box. Even the strip of pale curtain at the far left plays a role, a vertical interval of cool light that lets the eye breathe before returning to the saturated center. Ornament thus acts as architecture—flexible, rhythmic, and essential.

The Nude And The Ethics Of Ease

The odalisque tradition can slide toward voyeurism, but Matisse’s handling leans toward hospitality. The model’s posture is relaxed and unscripted; she meets neither mirror nor viewer with a theatrical glance. Jewelry and hair are notes rather than trophies. The body is neither hard nor saccharine; it retains a very human weight. By embedding the figure inside a network of patterns and life-signs, the painting encourages a kind of looking that is steady and respectful. The erotic is present as warmth and proximity, not as spectacle.

Light As A Warm Envelope

The light is domestic and warm, entering from the left and upper zones with no harsh glare. Whites soften into creams; shadows stay colorful. On the skin, light turns elegantly around shoulders and thigh with the help of cool gray notes at the edges. Glass catches small highlights on the fish jar and the fruit bowl, confirming their material without demanding attention. This even, warm light unifies the painting. It permits saturated color without aggression and allows varied textures to share the same air.

Dialogue With The 1912 Goldfish Paintings

Comparing this canvas with the 1912 “Goldfish” series clarifies Matisse’s evolution. In 1912 the fish were often central, the container a vertical cylinder set on a table with potted plants, and the palette heightened by citrus oranges, emeralds, and pinks. By 1922 he relocates the motif to the periphery of a larger domestic theater. The jar is darker, lower, and integrated into a fabric world. The color key drops a register into earth tones and brick reds. The compositional message changes accordingly. Where 1912 celebrates attentive contemplation and the optical flip of reflections, 1922 weaves contemplation into the everyday. The fish are not a separate world; they are neighbors to cushions, fruit, and a resting person.

Materiality And The Pleasure Of Things

Matisse never treats objects as tokens alone; he lets their material presence register. The carpet feels woven because marks alternate in value and hue; the cushion is downy because edges melt and the light sits softly on the crest; the wooden stand reads as carved because the contour swells and recedes like a turned spindle. The jar is heavy ceramic rather than laboratory glass, with thick, dark walls that make the water appear pewter. These material signals enrich the viewer’s bodily sense of the room. One can almost imagine the coolness of the jar, the nap of the carpet, the slick skin of fruit. Such tactile cues anchor the color music in lived reality.

Rhythm, Repetition, And Visual Music

The painting’s visual music depends on repeated forms and intervals. Circles echo between fish, fruit, necklace beads, and bowl. Diagonals recur in the angle of the striped cushion, the fall of the figure’s torso, and the slant of the hanging textile’s lower edge. Small black marks—on the carpet, in the hair, in the patterned textile—act like rests in musical notation, absorbing energy and resetting tempo. These repetitions prevent the eye from getting trapped in any one corner. They also give the viewer an embodied experience of time as the gaze loops from fish to fruit to face to cushion and back again.

The Viewer’s Path And The Experience Of Looking

The painting invites a specific itinerary. The eye enters at the bright white cushion, slides to the fish jar where orange flashes, passes across the striped cushion to the nude’s thigh and torso, pauses at the necklace and face, and then travels to the fruit stand whose circular top returns the gaze to the jar. Each circuit is slightly different, as if one were circling the room. The path is slow, deliberate, and reassuringly rhythmic. The canvas becomes a device for measured attention—a way to feel steadiness in a saturated world.

The Intelligence Of Omission

Many details are withheld. The pattern on the carpet is abbreviated to essentials; the wall textile does not advertise its weave; the model’s facial features are indicated with a few dark strokes. These omissions clear space for the core relationships to resonate. They also calibrate intimacy. By declining hyper-detail, Matisse lets the room remain generalized enough for the viewer to inhabit imaginatively while remaining specific enough to feel real.

Emotional Weather And Lasting Resonance

The emotional temperature is warm and unhurried. Reds and ochres cozy the space without smothering it; greens and grays cool the shadows and save the palette from heaviness. The goldfish provide light movement, an idea of time passing gently. The overall mood is one of a quiet afternoon indoors—work suspended, attention free to roam among bodies and things. The painting endures because it demonstrates that fullness does not require spectacle. A few tuned colors, confidently drawn forms, and living signs can produce a world large enough to rest in.

Conclusion: Body, Water, Fruit, And Fabric In A Single Breath

“Nude with Goldfish” gathers the elements of Matisse’s Nice interiors into a compact, lucid composition. A resting body, a vessel of fish, a bowl of fruit, and a field of textiles are balanced with a mature economy that trusts color and contour to do the work of narrative. The goldfish motif returns transformed—from an emblem of contemplative vision to a neighbor in a domestic harmony. Nothing shouts; everything cooperates. The result is a room that feels both intimate and complete, a picture where life’s simple sustainers—water, food, rest, and attentive looking—share the same warm breath.