Image source: wikiart.org

Historical Context And Matisse’s Interior Turn In The Early 1920s

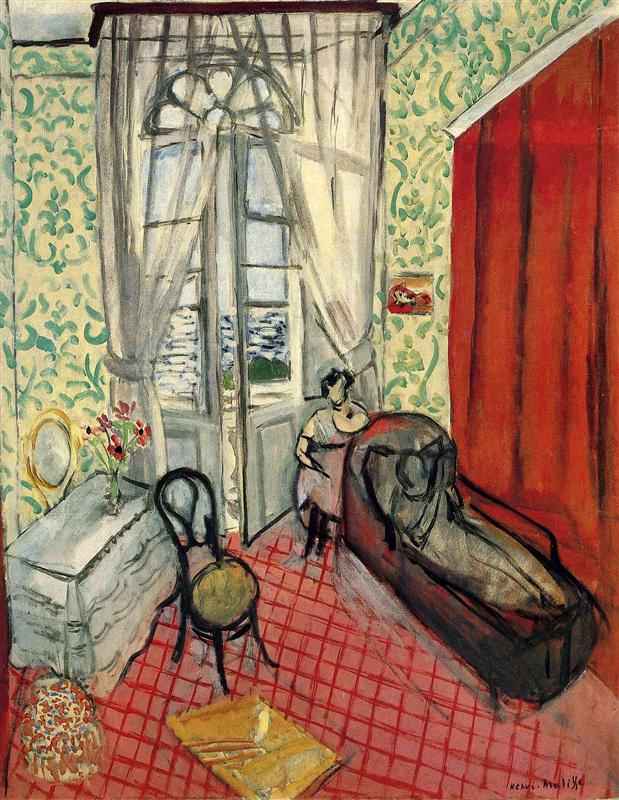

Henri Matisse painted “Two Women in an Interior” in 1921, amid a sustained exploration of rooms, balconies, and open windows that marked his Nice period. After the turbulence of the 1910s, he pursued a quieter but no less radical project: to build entire worlds from ornamental pattern, translucent light, and simplified figures. The studio and the hotel room became theaters where color and contour could converse without the need for grand narratives. This painting belongs to that investigation. It offers not only a portrait of domestic space but a meditation on looking, staging a dialogue between interior and exterior, between the prosaic furniture of a room and the imaginative freedoms of paint.

Composition As A High-View Stage

The composition is organized from a slightly elevated viewpoint that allows the floor to fan outward as a red, cross-hatched plane. This vantage compresses the room into a shallow stage where every object is legible. At the center stands a pair of French windows. Their panes open onto a tight slice of sea and sky, a vertical ribbon of exterior held between pale curtains that billow like sails. At the right, a long chaise or couch tilts diagonally toward the lower edge, becoming a dark anchor for the composition. Opposite it, at the left, a pale table runs parallel to the windows, bearing a glass vase of flowers and a small mirror whose oval rim repeats other rounded forms across the scene. Two chairs appear as black armatures—one near the table, one turned toward the chaise—punctuating the space with curved silhouettes. Near the center-bottom, a folded screen or folio lies on the floor like a small golden kite. Everything is placed to guide the eye in a loop: from the bright floor up to the windows, across the patterned walls, down the red curtain, and back through the furniture to the flowers on the table.

Patterned Walls And The Architecture Of Ornament

The wallpaper’s mint-green arabesques are not mere decoration. They create a breathing architecture behind the furniture, a flexible grid that counterbalances the rigidity of window frames and door mouldings. The pattern’s leafy scrolls echo the curves of chair backs and the oval mirror, knitting object and background into one fabric. By letting the pattern show through in some places and thin out in others, Matisse converts the wall into a living surface whose rhythm affects the whole room. Against this springlike field, the red curtain at the far right reads like a dramatic proscenium. Its vertical swath deepens the stage, introducing a warm mass that holds the eye while preventing the composition from dissolving into airy coolness.

The Window As Motif And Idea

Few motifs mattered more to Matisse than the open window. Here it is a portal and a measuring stick. Through the panes we glimpse the Mediterranean, rendered with short, broken strokes of blue and white that vibrate against the window’s verticals. The exterior is small in area but large in consequence. It verifies the light that suffuses the room, explains the flutter in the curtains, and promises that beyond the patterned cocoon lies an open, sparkling world. Yet the window also insists on painting’s autonomy. The outside is framed and translated into stripes and ripples, becoming a pattern among patterns. The window is therefore an idea about seeing: the world filtered through a human vantage, organized by edges, and translated into a set of tuned relations.

The Two Women As Nodal Presences

The title names two women, but Matisse refuses anecdotal storytelling. One sits on the edge of the chaise, body angled toward the window, head slightly bowed as if caught in a moment of thought. The second is present more implicitly: she may be the unseen occupant whose reflection would surface in the oval mirror, or the viewer whose gaze animates the room. In many Nice-period interiors the feminine presence is a calm center around which fabrics and light circulate. Here the seated figure acts as a tonal hinge. She is drawn with dark contours that clarify the chaise’s form and the passage between floor and windows. Her face is simplified to a few decisive strokes; her arm, indicated by a swelling line, leads the viewer toward the window. By keeping the figures understated, Matisse protects the painting from theatrical narrative and lets relation—woman to window, woman to couch, woman to patterned walls—carry the drama.

Drawing Inside The Paint

The black line is authoritative, but it never cages the color. Matisse draws with a loaded brush that thickens and thins like calligraphy. The chaise’s profile is a continuous, elastic contour; the chair backs are nimble arabesques; the window mullions snap into place with a carpenter’s economy. These lines sit on top of broad planes of color that have been scrubbed, scumbled, and occasionally allowed to leave raw breaths of ground. The combination creates a sensation of speed without haste. You feel the artist’s hand decide, correct, and confirm. The drawing is not a separate step; it is an event inside the painting, carrying structure and tempo at once.

Color Chords And Temperature Balances

The palette hinges on three families of color: the cool mint of the wallpaper, the warm red of the floor and curtain, and the stony grays and lavenders of the window woodwork. The bouquet and the small accents—yellow in the floor object, blue in the seascape, green in chair seats—sound like grace notes around this chord. Matisse balances temperatures with exactness. The red lattice of the floor heats the lower half of the canvas while the mint walls cool the upper field. The gray window posts act as moderators, calming the exchange so the painting never tips into sugary prettiness or brutal contrast. The overall effect is buoyant but grounded, like a room filled with midday light that remains comfortable rather than glaring.

Spatial Construction Without Illusionist Tricks

Perspective is present but softened. The floor’s grid implies recession, yet it is not calculated with ruler and vanishing point. Instead, the grid’s diamonds compress gently as they rise, giving the floor a felt tilt more than a measured one. The chaise and table are drawn as solid volumes, but their contours are elastic enough to keep them from becoming heavy. The windows are the strictest geometry—vertical, orthogonal, rectangular—so that their stability can host fluttering curtains and the flicker of sea beyond. Matisse constructs space as a set of interlocking planes whose relationships are clarified by line and temperature rather than by academic perspective. The viewer feels oriented without being pinned to a single point in space.

Light As A System Of Pale Veils

Light enters from the window and disperses as a system of veils. The curtains are milky washes that record the light’s passage; the tablecloth is a chalky, cool panel that catches it; the wallpaper reflects it with springlike gaiety. Shadows are seldom heavy. Instead, Matisse cools colors slightly where planes turn away from the source, keeping the painting buoyant. The figures and furniture cast only the most necessary of shadows, which keeps the room from thickening into theatrical chiaroscuro. This approach to light sustains the Nice period’s promise: interiors as sanctuaries of clarity where color can be fully itself.

Furniture, Flowers, And The Ethics Of Domesticity

Objects in the room are not trophies; they are working parts of a life. The chaise invites sitting, the chairs imply conversation or pause, the table holds flowers arranged in a clear vase that declares its water with a handful of quick strokes. The bouquet’s reds and whites cross the room to the red curtain and the couch’s light drapery, making a circuit that ties the domestic scene together. The oval mirror is turned just enough to withhold a direct reflection, preserving privacy while acknowledging self-regard as part of the room’s life. Matisse’s ethical stance is palpable: the domestic sphere is neither trivial nor sentimental; it is a site where attention, care, and repose produce meaning.

The Red Curtain As A Vertical Event

The great slab of red at the right reads as both curtain and chromatic wall. It deepens the composition, generates a warm updraft that meets the cool wallpaper, and acts like a conductor’s downbeat that sets tempo for the whole. Its vertical pleats are barely notated; the color itself does the work. By allowing such a large unpatterned field to coexist with the intricate floor and wall, Matisse displays confidence in large shapes. The curtain shows how modern painting can use expanses of color as protagonists equal to figures and objects.

The Sea Beyond And The Promise Of Movement

The small patch of sea glimpsed through the panes is painted with horizontal dashes that suggest wind ruffling the surface. Although tiny, this element changes the painting’s energy. It tells us the room is not sealed; air moves, weather changes, time passes. The open window has cultural weight in Matisse’s oeuvre—freedom, travel, breath—but in this canvas the sea is also a compositional tool. Its blue is the coolest color in the picture, and that coolness calibrates every surrounding temperature. The room’s warmth feels warmer because the sea is there to steady it.

The Psychology Of The High View

The elevated perspective carries psychological implications. We look down gently on the scene, not as a surveilling presence but as someone invited to hover. The viewpoint allows us to understand the room’s order and to witness the women’s quiet companionship without intruding. Because nothing is dramatically foreshortened, the view encourages a contemplative rather than a sensational response. The painting thus models a posture of respectful looking, one that Matisse prized: the viewer is near enough to feel the textures of life and distant enough to let the scene keep its privacy.

Rhythm, Repetition, And Visual Music

Matisse builds visual music through repeated forms. Ovals echo from mirror to chair seats to curves of the chaise’s arm. Vertical bars answer across window mullions and curtain folds. The floor grid keeps time like a percussion track, regular yet softened at the edges by the brush. These repetitions establish tempo, and their slight variations prevent monotony. The eye moves in phrases—up the window, across the cornice, down the curtain, around the chaise, back to the table and flowers—each phrase resolving into the next. The sensation is not of restless scanning but of paced, almost audible rhythm.

The Intelligence Of Omission

Wherever detail would clutter, Matisse omits. He does not model the bouquet petal by petal; he turns blossoms into pale disks with a stroke or two. He refuses to articulate upholstery seams or tabletop grain; he lets a single contour and a temperature shift render volume. The seated woman’s face is simplified to preserve the painting’s calm. These omissions are not shortcuts; they are decisions about where meaning lives. In this room, meaning is found in relations of mass, color, and rhythm. By withholding distraction, Matisse allows those relations to register fully.

Continuities And Departures Within Matisse’s Work

“Two Women in an Interior” converses with earlier Fauve experiments and later distillations. The high-key color and fearless pattern recall 1908–1911 interiors, yet the palette is moderated, with grays and lavenders stabilizing the chord. The calligraphic drawing anticipates the linear authority of Matisse’s 1930s drawings, while the large red curtain prefigures the monumental color fields of his late cut-outs. Within the Nice-period sequence, this painting sits where theatrical ornament meets lucid construction, the exact balance Matisse sought for several years: to keep pleasure generous and form clear.

The Viewer’s Path And The Experience Of Time

The painting offers a specific path. You rise from the floor’s golden folio, travel along the grid to the seated woman and chaise, ascend the window panes to the sea, follow the curtain down like a velvet slide, and return by way of the table and flowers. Each circuit takes seconds, but the room seems to lengthen time. Nothing demands urgency. The two women—one visible, one implied—seem settled into a routine that values pauses. Matisse transforms time into pattern, giving the viewer an experience of duration that is restful rather than passive.

Emotional Weather And The Poise Of Calm

The emotional register is poised calm. Reds and greens could quarrel, yet here they converse. The curtains could flutter anxiously, yet they breathe. The figures could dramatize interiority, yet they inhabit it with ease. This calm is not blandness but resolution—the feeling that each element has negotiated its place with neighboring elements. The painting becomes a model of peaceful coexistence between contrasts: warm and cool, near and far, solid and airy, public view and private life.

Lasting Relevance And The Promise Of The Room

The work remains relevant because it teaches how to make a complete world from a small number of tuned parts. In an age crowded with images and objects, Matisse proposes a room where attention itself furnishes the space. The painting suggests that beauty can be built from measured relations rather than from accumulation. It dignifies domestic life without sentimentalizing it and demonstrates how art can hold the outside world at a respectful distance while letting its light in.

Conclusion: A Chamber Of Light, Rhythm, And Quiet Companionship

“Two Women in an Interior” distills Matisse’s mature values into a single, lucid room. Patterned walls breathe, a large red curtain steadies the orchestra, the sea flickers beyond, and furniture takes its place like characters in a chamber play. The figures are modest but decisive nodes around which color and contour organize themselves. The drawing is calligraphic, the color chord balanced, the spatial logic clear without pedantry. The painting endures because it models an ethic of attention—serene, exact, and hospitable—offering a chamber where light and human presence share the same patient rhythm.