Image source: wikiart.org

Historical Moment And Setting On The Normandy Coast

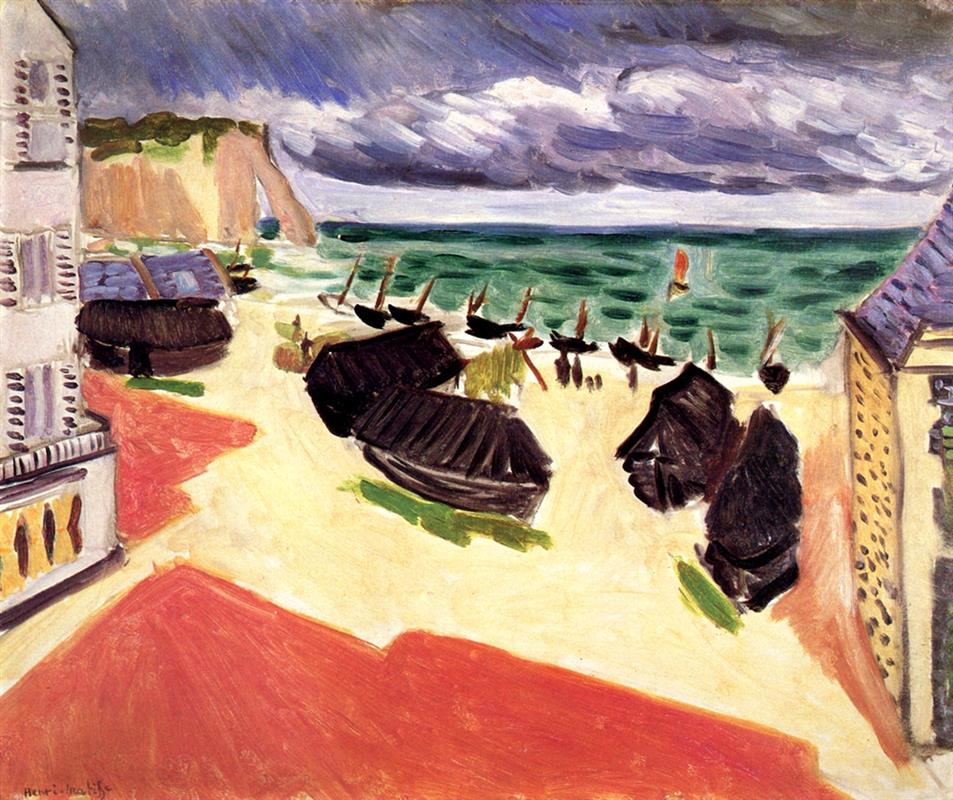

Henri Matisse painted “Fishing Boats in Winter, Etretat” in 1921, returning once again to the Norman shoreline that had become a recurring laboratory for his mature ideas about color, structure, and the sensation of air. Etretat’s beach, cliffs, and hard winter light offered a subject familiar to French art yet flexible enough to receive the modern simplifications he had honed since his Fauve years. The year matters. By 1921 Matisse was no longer chasing shock through intensity alone. He had absorbed the turbulence of the 1910s and settled into a confident economy in which pared forms and tuned color relationships could carry an entire narrative of weather, place, and mood. Etretat had attracted painters from Courbet to Monet; Matisse acknowledges that lineage while bending it to his own vision, trading atmospheric shimmer for a decisive orchestration of planes and masses. Winter removes the distractions of summer leisure, leaving boats, architecture, cloud, and sea to speak with elemental clarity.

Composition As A Broad Fan Of Planes

The composition opens like a fan from the lower left to the upper right, establishing a sweeping movement across the beach that simultaneously invites and organizes the viewer’s gaze. Large terracotta-red forecourt shapes occupy the immediate foreground, angled as if they were paving or a courtyard terrace, and they act as launchpads for the eye. From there, the creamy sand field takes over, punctuated by dark boat hulls arranged in staggered intervals that reinforce recession without resorting to fussy perspective. The cliff at left and the masonry at right serve as anchoring verticals, compressing the scene into a shallow, legible stage. The horizon slices the top third of the canvas, locking sky and sea into a horizontal counterpoint against the diagonal thrust of the beach. Matisse achieves a surprising depth with minimal means. Rather than construct linear perspective grids, he uses scale, tonal contrasts, and directional brushwork to cue distance. The boats nearer to us are heavy, nearly sculptural, while the ones along the surf shrink into calligraphic silhouettes. The result is a space clarified by rhythm rather than by measured lines.

The Boat As Form And Sign

The boats are the painting’s protagonists, but Matisse treats them as forms and signs more than as literal vessels. The nearest boat is an oblong block of dark paint whose ribbing is suggested by striated strokes. It wears its mass like armor, a grounded presence that speaks of work and weight. As the boats recede, they simplify into black marks with notched masts, each mark delivering a different articulation of the same idea. These variations keep the eye active, roaming from shape to shape as though reading a line of script. Importantly, none of the boats is so individualized that it asks for narrative attention. The emphasis remains on their collective rhythm across the strand, a chorus of hulls unified by work and season. In winter the boats are hauled up, covered, or idle, and their dark coverings become compositional wedges that press against the pale sand, testing its brightness and confirming its chill.

Weather Written In Color Blocks

Weather is not simply announced by clouds; it is written into the entire chromatic architecture. The sky occupies the top belt like a slate curtain pulled across the scene, built from broad strokes of gray-violet and blue that lean toward storm but stop short of drama. The sea is a saturated green punctuated by darker troughs, a mass whose cool heft answers the warm foreground. The beach is not the golden, sparkling stage of high summer; it is an off-white field with faint ochre and pink undertones, the color of cold sand that has shed its heat. The terracotta shapes in the foreground inject a counter-temperature, as if the human-made plane retained a little warmth against the winter air. This thermal dialogue animates the picture. Matisse’s palette is not extravagant, yet every area is alive with purposeful temperature shifts that coordinate mood and structure.

Brushwork And The Velocity Of Seeing

The brushwork demonstrates a range of velocities aligned to the subject’s character. In the sky, long, laterally dragged strokes pile into one another, echoing the wind-driven stacking of clouds. Over the sea, the brush oscillates into small arcs and flattened dashes, registering the water’s layered movement and the restless texture of winter waves. On the beach, strokes become shorter and rounder, stippling the surface to suggest pebbles, footprints, and raked sand without specifying any single object. The boats receive firmer, directional striations that suggest planks, tar, and canvas. This distribution of touch produces a tactile map of the scene. The painting refuses illusionistic polish, but it does not forsake description; it simply replaces literal detail with the sensation of making. Looking becomes analogous to touch, and the surface reads like a record of observed speed.

Architecture As Bracket And Counterpoint

The buildings on the left and right edges complete the orchestration. On the left, a pale façade with shuttered windows stands in cool rapport with the beach’s warmth. Its verticality tempers the diagonal carry of the composition, and its cool whites and violets keep the color chord from becoming top-heavy with warmth. On the right, a narrow slice of ochre masonry with dark, pebble-like spots acts as a bookend, a textured counterweight that returns the eye inward. These structures also root the scene socially. They subtly insist that this is not a timeless shore but a site of habitation, trade, and shelter. Matisse paints them with the same economy used elsewhere, presenting just enough information—shutter slats, balcony rail, roofline—to make them legible without stealing energy from the central dance of boats and sand.

The Cliff And The Genealogy Of Motifs

The chalk cliff of Etretat enters from the left like a stage flat, its pale mass catching a blush of warm light near the top where the sun finds it through the cloud cover. Matisse reduces its notorious theatrical shape to a soft-edged wedge, acknowledging the landmark without letting it dominate. In the genealogy of French coastal motifs, cliffs often claim center stage, but here the cliff is an aside, a reminder of place that gives the boats more authority. By downplaying the cliff’s emblematic arches, Matisse aligns the painting with workaday rhythms and with the humility of winter maintenance. He modernizes the motif by refusing the sublime in favor of the ordinary made luminous.

Tonal Architecture And The Balance Of Masses

Although Matisse is reputed as a painter of color, the tonal architecture of this canvas deserves special notice. The dark values are concentrated in the boats and in the architectural flanks, forming a loose horseshoe that encloses the sand’s high value. The sky is a mid-tone field that keeps the dark masses from rising too aggressively to the top. This distribution stabilizes the scene. The darkest forms, heavy and earthbound, cluster close to where labor happens. The sea is darker than the sand but lighter than the boats, an in-between register reflecting its role as both threat and sustenance. Such tonal decisions are not academic exercises; they are ethical choices about how weight and light should inhabit the world of the painting.

The Season As A Way Of Seeing

The title specifies winter, and the canvas earns that designation without resorting to snow or bare trees. Winter is present in the shorter chromatic scale, the subdued luminosity, the thicker coverings of boats, and the sense of pause rather than bustle. The air feels denser, and the distances compress slightly under the low light. By painting winter without cliché, Matisse demonstrates how season is as much a way of seeing as it is a set of meteorological facts. A small sail with a russet note on the horizon pricks the cool sea with a needed ember, like a stove-flame in a gray room, confirming that work continues despite the weather.

Human Presence And The Ethics Of Modesty

Figures, if present at all, are reduced to tiny notations along the surf line. Their modesty is deliberate. Matisse refuses to turn workers into anecdotes or decorations. Instead, he gives them a proportional dignity within the landscape of labor. The painting respects human effort by reserving its descriptive bravura for the tools and conditions—the boats, the sand, the wind—within which that effort unfolds. By not individualizing faces, he avoids sentimentality and opens space for viewers to project a broader human story about coastal life in the off-season.

Continuity And Difference Within Matisse’s Window-And-Beach Series

Viewed alongside Matisse’s other Etretat paintings and his many window pictures, this canvas reveals both continuity and difference. Like “Open Window at Etretat,” it frames a coastal subject but dispenses with an explicit interior frame, placing us on a balcony or terrace so near the beach that architecture becomes a sideways bracket rather than a proscenium. Compared with the electric chroma of earlier Fauve works, the color here is quieter, keyed to real winter light. Yet it is no retreat. The courage lies in restraint, in trusting a limited chord to carry the full music of the scene. The planar simplifications anticipate later decades when Matisse would privilege clear shapes and distilled contrasts, culminating in the cut-outs. One can feel, in the boats’ flattened silhouettes and the beach’s big fields, a desire to make the world legible with the fewest possible marks.

Drawing Inside The Paint

Matisse’s drawing is embedded in the paint rather than laid on top. The edges of the boats are formed by the meeting of dark and light fields, not by lines marching around shapes. The masts are single, elastic strokes that flex with the imagined wind. The cliffline is a softened contour whose slight wavering avoids storybook cutout crispness. This approach allows drawing to breathe with the painting, so that form is generated by color and value decisions rather than corralling them. The effect is an image that reads as both constructed and alive.

The Drama Of Edges And Intervals

The drama of this painting sits at the edges and intervals where one field meets another. The meet between sea and beach is a mutable, frothy seam, rendered by broken strokes that convey exchange rather than boundary. The juncture between the terracotta forecourt and the sand is firmer, signaling the passage from human-ordered space to the natural strand. The right-hand wall’s spotted texture grinds against the smoothness of the sand, rehearsing in miniature the painting’s greater theme of worked surface versus open expanse. These transitions animate the canvas, ensuring that the eye never idles in large zones but skims along seams where meaning is made.

A Painting Of Labor Without Spectacle

There is no storm, no shipwreck, no heroic fisherman at center stage. Yet the painting is saturated with labor. The hauled boats, the stacked covers, the angling masts, the faintly rutted sand all testify to work done and work waiting. Matisse understands that the truth of coastal life often lies in maintenance and preparation, especially in winter when the sea’s generosity and danger are equally apparent. By declining spectacle, the painting honors the repetitive dignity of daily tasks and preserves the viewer’s capacity for quiet attention.

The Viewer’s Path And The Experience Of Looking

The composition choreographs a specific path for the viewer. You begin at the left terrace, feel the cool façade, step onto the warm red plane, drift into the pale sand, and then travel along the arc of boats to the green water and the brooding sky. On the way back, the right-hand wall checks your movement and returns you toward the center. This path repeats, slowly tightening into a meditative loop. The painting thereby becomes an instrument for a particular kind of looking, one that alternates between immersion in broad fields and focus on small, decisive marks. It is a rhythm akin to breathing in cold air—deep, deliberate, clearing.

The Intelligence Of Omission And The Pleasure Of Clarity

Every omission here is intelligent. We are told nothing of individual faces, nothing of the innards of boats, little of architectural detail, and only the broadest information about cloud types. What we receive instead is clarity of relation. Boats relate to sand by weight and temperature, buildings relate to beach by angle and color, sky relates to sea by stroke and value. This clarity offers pleasure, not the sugar of decorative excess but the nourishment of understanding. It is the kind of pleasure that lingers, because it arises from coherence that the viewer helps complete.

Dialogues With Precedents And With Modern Life

“Fishing Boats in Winter, Etretat” converses with the long tradition of French marines while answering to the conditions of modern life. Where earlier painters often sought sublime grandeur or anecdotal charm, Matisse opts for lucid construction. His scene is recognizably a working shore in a specific season, yet it is also an abstract concert of shapes and temperatures. That dual allegiance—to the seen world and to the autonomy of painting—places the work squarely within modernism’s central problem and showcases Matisse’s gentle resolution. He neither abandons subject nor bows to it; he allows subject and structure to be mutually illuminating.

The Painting’s Emotional Weather

The emotional weather of the picture is composed rather than sensational. The brooding sky does not menace; it broods with purpose, a weight that concentrates rather than depresses. The greens of the sea are cool but not bitter. The reds in the foreground warm the composition without tipping it into coziness. The overall mood could be called bracing calm, the feeling of being outdoors on a winter day when work must be done and the body, once warmed by effort, registers the air as clear rather than punishing. This mood is inseparable from the order of shapes, as if clarity of arrangement itself were an ethical balm.

Legacy And Contemporary Resonance

Today the painting reads as fresh because it models how to see complexity as order without simplifying it into banality. In a world saturated with imagery, the canvas demonstrates restraint and attentiveness. It allows a viewer to experience place through a handful of tuned relationships rather than through exhaustive description. For artists and designers, it remains a textbook on balancing large masses with small accents, on using temperature to imply weather, and on letting drawing arise from color. For general viewers, it offers an accessible invitation to pay attention to ordinary spaces when the fanfare of summer is gone. Winter becomes not absence but structure.

Conclusion And The Quiet Brilliance Of Winter Work

“Fishing Boats in Winter, Etretat” is a masterclass in how pared means can deliver a full sense of reality. The sweeping composition, the concentrated darks of the boats, the cool sea, the brooding sky, the architectural bracketing, and the warm forecourt all interlock to tell a story of season, labor, and place. Matisse’s brush declares its movements openly, leaving a surface that is both legible and alive. Instead of staging heroics, he finds poetry in maintenance and clarity in pause. The painting’s lasting brilliance lies in this quiet conviction that the world, properly framed and tuned, is already charged with feeling. Winter is not a lull in vision but a time when forms speak with particular honesty, and Matisse listens closely enough to translate their language into a lucid, enduring image.