Image source: wikiart.org

Historical Context And The Return To The Window Motif

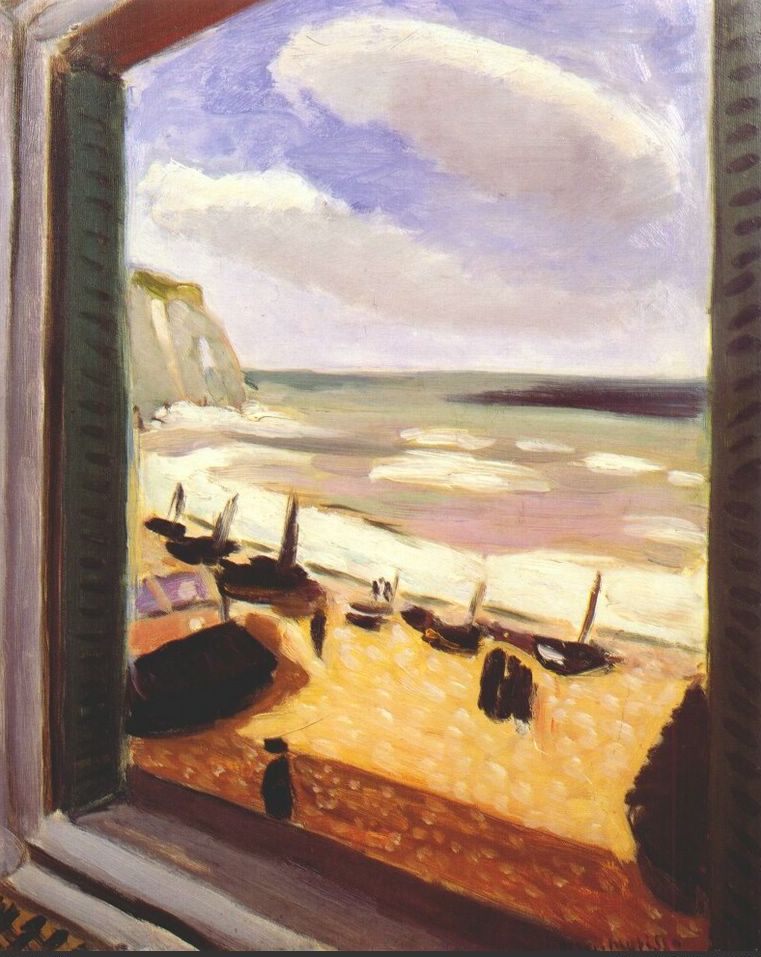

Henri Matisse painted “Open Window at Etretat” in 1921, at a moment when he was reflecting on the language of modern painting after the upheavals of the previous decade. The war years had complicated the optimism of early Fauvism, but Matisse remained committed to color as a source of structure and feeling. He had already used the window as a central motif many times, beginning with the seminal “Open Window, Collioure” in 1905. By 1921 the window had become more than a convenient frame: it was a studio device for staging a conversation between interior and exterior, control and spontaneity, art and life. In Normandy, at Etretat, the motif acquires a coastal character. The breeze, the fleeting clouds, and the small boats bring the ocean’s tempo into the room, while the dark edges of the sash assert the quiet order of painting itself. The date is crucial because it reveals an artist consolidating decades of experiments into a clear and economical idiom, confident enough to leave broad passages unmodeled and yet attentive to the rhythms of light across sand and water.

Composition As A Framed Threshold

The most immediate feature is the emphatic window frame, arranged like a proscenium that compresses the picture’s drama into a view. Matisse tilts the bottom ledge sharply, using it as a diagonal ramp that guides the eye from the left corner into the sunlit beach. The left jamb is a dark vertical, and the right side shows the greenish shutter with simplified slats. These borders function as metronomes for the eye, setting a beat against which the softer shapes of sea and sky play. The composition divides into three horizontal belts: a lower register of warm ochres and reddish browns for the beach, a middle band where green sea meets the foamy edge, and an upper expanse of lavender and blue sky punctuated by leisurely clouds. Within this tripartite scheme, small boats and figures become punctuation marks, never precise portraits but rather signs of activity. The framing device keeps this activity at a contemplative distance. We are not on the beach but inside, perceiving the scene through a human vantage. Matisse thus composes not only a landscape but an experience of looking.

Color As Atmosphere And Architecture

Color in this painting is both atmospheric and architectural. The beach glows with apricot and terracotta strokes that declare the sun’s warmth, while slate violets and malachite greens sift through the surf to cool the middle zone. The sky is painted with expansive lilac and light blue swathes, over which a cloud slides like a pale sail. These are not descriptive tints alone; they are structural planes that anchor the scene. Notice how the dark window edges are not neutral blacks but deep mixtures, the left edge tinged with green and the right shutter pulsing with greenish gray. Each hue participates in a system of complements. The oranges of the sand kindle the blues of the sky. The green sea steadies the red undertones in the sill. This choreography keeps the painting vibrating without losing balance. Matisse is famous for poetic color, but here poetry means precision. A few tuned notes, held across the canvas, generate a full chord of climate and place.

Brushwork And The Tactile Surface

The brushwork is frank, decisive, and of varied tempo. In the beach, short rounded touches stipple the surface, suggesting pebbles and sunbursts without describing any pebble in particular. Along the waterline, broader horizontal drags of paint deliver the calm glide of the tide. The sky receives slower, fuller strokes, so that the clouds feel suspended rather than frozen. The shutter is built from stacked, deliberate marks that echo carpentry. Importantly, Matisse leaves traces of the brush at the edges, where one color meets another, so the painting breathes through minute halos rather than hard outlines. This permeability reiterates the theme of an open window: inside and outside exchange air at the level of pigment. The paint’s thickness varies too. Some areas are thin and scumbled so the ground peeks through, letting light mingle optically. Others are buttery, delivering a sense of immediacy that moves at the speed of his hand. The surface is therefore a diary of looking in time.

Light, Weather, And The Rhythm Of The Coast

Light in Etretat is notoriously changeable, and Matisse builds that capriciousness into the very rhythm of the picture. The cloud’s large ovoid casts no theatrical shadow; instead, it imposes a soft tempo change in the sky’s color. The sea is shown neither stormy nor glassy but in a middle mood, with pale strokes like foam patches carrying visual syncopation. On the beach, warmth is concentrated, and the human presence is reduced to minimal signs, which prevents anecdote from distracting us from the general feeling of a windy but generous day. Weather is expressed more by tempo and temperature of color than by narrative incident, and the result is a painting you can almost hear: a hush inside the room, a muffled clatter of boats, and the distant constant of surf.

Space, Perspective, And The Tilted Plane

The geometry is simplified but canny. The sharply angled sill acts like a perspective accelerator that pushes us outward, while the verticals of the jambs pull the scene back into planar stability. The coastline along the left introduces a cliff that rises almost like a curtain, offsetting the open expanse to the right. Boats are scaled to accentuate recession without the need for elaborate linear perspective. Matisse uses size shifts and tonal contrasts to stage depth: darker, larger forms in the lower left read as closer; smaller, darker dots toward the horizon compress into a frieze. Space seems to hinge at the waterline, a choice that privileges the meeting of elements as the painting’s spatial fulcrum. The window, then, is not simply a border but a device that clarifies relationships among planes.

The Window As Idea

For Matisse the window is a studio philosophy. It turns the act of looking into the subject of the picture. In an open window, the artist negotiates between control and generosity. The interior affords the conditions for painting, a stable frame with edges and a vantage; the exterior supplies the gift of change. “Open Window at Etretat” stages this negotiation with particular tenderness. Nothing in the interior is described except the frame itself. We are given only the threshold, not the whole room, as if to say that true attention begins by acknowledging the frame through which we see. The window becomes a metaphor for painting’s pact with the world: neither a sealed icon nor a literal transcription, but a membrane where perception becomes form.

Étretat And The Lineage Of Coastal Views

Etretat, with its cliffs and pebbled shore, had long lured painters. Courbet, Monet, and many others found in its rock formations a theater for light. Matisse’s response is notably intimate. He declines the grander spectacle of the famous arches and instead selects the everyday theater of boats drawn up on shore. This shift in emphasis places him within yet apart from the lineage. He inherits the coastal subject but translates it into the language of interiority. The cliff slips into the left margin, a reminder of place rather than a headline act. The boats, humble and graphic, tether the composition to the labors of people. Matisse compresses the sublime into the scale of a window, suggesting that grandeur can be felt in modest increments of color and air.

Human Presence And The Ethics Of Distance

A small vertical silhouette on the beach can be read as a figure, but it is closer to a glyph than a portrait. This near-anonymity reflects a gentle ethics of distance. Matisse’s art rarely indulges in voyeurism; instead it cultivates hospitality. By holding back from descriptive detail on the people, he allows the viewer to inhabit the scene without prying. The result is empathy at the scale of a mark. The boats, similarly, are generalized shapes, black or dark brown ovals with hints of mast and hull. They are not inventories of rigging but notes about work, rest, and cycles. The painting respects the people and their tools by giving them the dignity of rhythm rather than the burden of anecdote.

Comparison With Earlier And Later Windows

Compared with the explosive chroma of “Open Window, Collioure” from 1905, this work is more tempered, but not less radical. The palette is lower key, a decision consistent with the colder northern light and with Matisse’s mature confidence. He no longer needs extremes to make color decisive; small differences do the work. If one sets this painting alongside Nice interiors from the late 1910s and early 1920s, one notices that the ornamental profusion of fabrics and furniture in those canvases yields here to near-abstraction. Only frame, shutter, and ledge remain. The painting thus foreshadows the further simplifications of the 1930s and, ultimately, the cut-outs, where edges and planes become sovereign. “Open Window at Etretat” is a hinge in this progression, preserving the generosity of observation while advancing toward the clarity of shape.

Material Economy And The Intelligence Of Omission

Much of the painting’s elegance comes from what Matisse refuses to state. There are no reflected highlights on glass because the window is already open. There are no beads of moisture or grains of sand described one by one. Instead, a small modulation of temperature carries the impression of sparkle. This economy is not laziness but intelligence: the viewer completes the world from cues. The intelligence of omission also keeps the image light, in both senses. The canvas never becomes heavy with excess description, and the daylight seems to permeate every layer. The few accents of darker paint serve to anchor the eye, but they never imprison it.

Movement Between Inside And Outside

Although the interior is barely given, one feels oneself inside because the frame surrounds us. This paradox—an interior defined by its edge—creates a dynamic movement in which the viewer repeatedly crosses the threshold with the eyes. The diagonal sill sends the gaze outward; the verticals pull it back. The rhythm is gentle but persistent, producing a contemplative sway that mirrors the sea’s own back-and-forth. Many painters have attempted to capture motion by depicting moving things, yet Matisse generates motion through the viewer’s path. The painting is kinetic in the mind.

Time Of Day And The Sense Of Occasion

The slant of light and the moderate length of shadows suggest late morning or mid-afternoon, times when work on the beach would likely pause for tides or meals. The scene conveys occasion without event. A cloud drifts, boats wait, a figure stands, and the sea continues. This is a theater of intervals rather than climaxes. By choosing such a moment Matisse allies painting with duration rather than drama. The mood is neither solemn nor festive; it is a lucid lull in which the world seems briefly aware of being seen.

Interplay Of Natural And Constructed Forms

The cliff on the left is a natural wall, echoing the vertical of the window jamb. The shutter’s repeating slats rhyme with the repetitive wavelets on the sea. The cloud’s rounded ovoid answers the oval hulls of the boats. The painting is riddled with these small correspondences. Such echoes are not decorative flourishes but structural analogies that knit interior carpentry, human craft, and natural phenomena into one fabric. This underlies Matisse’s belief that painting discloses affinities otherwise overlooked, a kind of visual ethics in which disparate orders find companionship.

Expressive Drawing Within Paint

While color is emphasized, drawing is quietly potent. The masts are single, confident lines. The horizon is a band, slightly softened to avoid slicing the picture in two. The edge of the cliff is a curving contour that resists diagrammatic stiffness. Matisse had spent years refining a calligraphic approach to drawing, and here that sensibility travels through the brush. Even the thick edge of the sill acts like a drawn line, a sweep that signals direction as much as it describes an object. The coexistence of calligraphic and painterly passages allows the composition to feel both designed and breathed.

Emotional Temperature And The Discipline Of Joy

Many writers have attached the word joy to Matisse, but in this painting joy is disciplined. It is not exuberance for its own sake; it is serenity earned by decisions. The colors are happy but not giddy. The brush is free but not careless. The open window promises freedom, yet the frame insists on form. This equipoise becomes the emotional temperature of the work. Viewers often report a rested feeling before the canvas, as if time has slowed to the pace of weather. That effect is inseparable from the painter’s restraint, whose discipline keeps pleasure sustainable.

Dialogue With Tradition And Modern Life

The window motif reaches back to Renaissance painting, where it signified a rational opening onto the world. Matisse inherits the concept but updates it for modern life by refusing illusionism. He does not pretend the window is a literal portal; he shows it as a painted edge. The beach scene is not a meticulously perspectival view; it is a constructed field of color. In this way the painting participates in a conversation with tradition while asserting modern autonomy. It accepts the world as source and declares painting as its own reality, hospitable to experience yet governed by its laws.

What The Painting Teaches About Looking

The painting invites viewers to practice a particular kind of attention. First, recognize the frame. Second, let the eye travel calmly across color fields without the compulsion to name each thing. Third, register the harmonies among shapes rather than scanning for anecdotes. Finally, return to the frame and notice how it changes the scene. After spending time with the work, one often finds that the world outside any literal window appears newly organized and musical. Matisse’s painting becomes a training ground for a gentler, more structural gaze.

Legacy And Relevance Today

“Open Window at Etretat” resonates with contemporary viewers because it reconciles two desires that still define our era: immersion in the world’s flux and a need for inward clarity. The ocean and sky promise infinite change, while the window provides a place to stand. In digital life we are deluged by images without edges; Matisse offers a model of framing that is both generous and firm. Museums and reproductions keep returning to this painting not simply for its beauty but for its ethic of attention. It demonstrates how a limited set of means—frame, horizon, boats, beach—can carry a wealth of feeling and thought.

Conclusion: A Calm Aperture On The Sea

“Open Window at Etretat” crystallizes Matisse’s mature understanding of painting as an art of thresholds. Through a remarkably simple arrangement, the work balances interior and exterior, discipline and delight, structure and weather. The color is selective yet radiant, the brushwork frank yet nuanced, the drawing minimal yet decisive. The result is an image that does not shout for attention but sustains it, an aperture through which air seems to pass. Standing before it, we feel not the hysterics of spectacle but the steadying pulse of a day lived near the sea. The window is open, and through it painting breathes.