Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

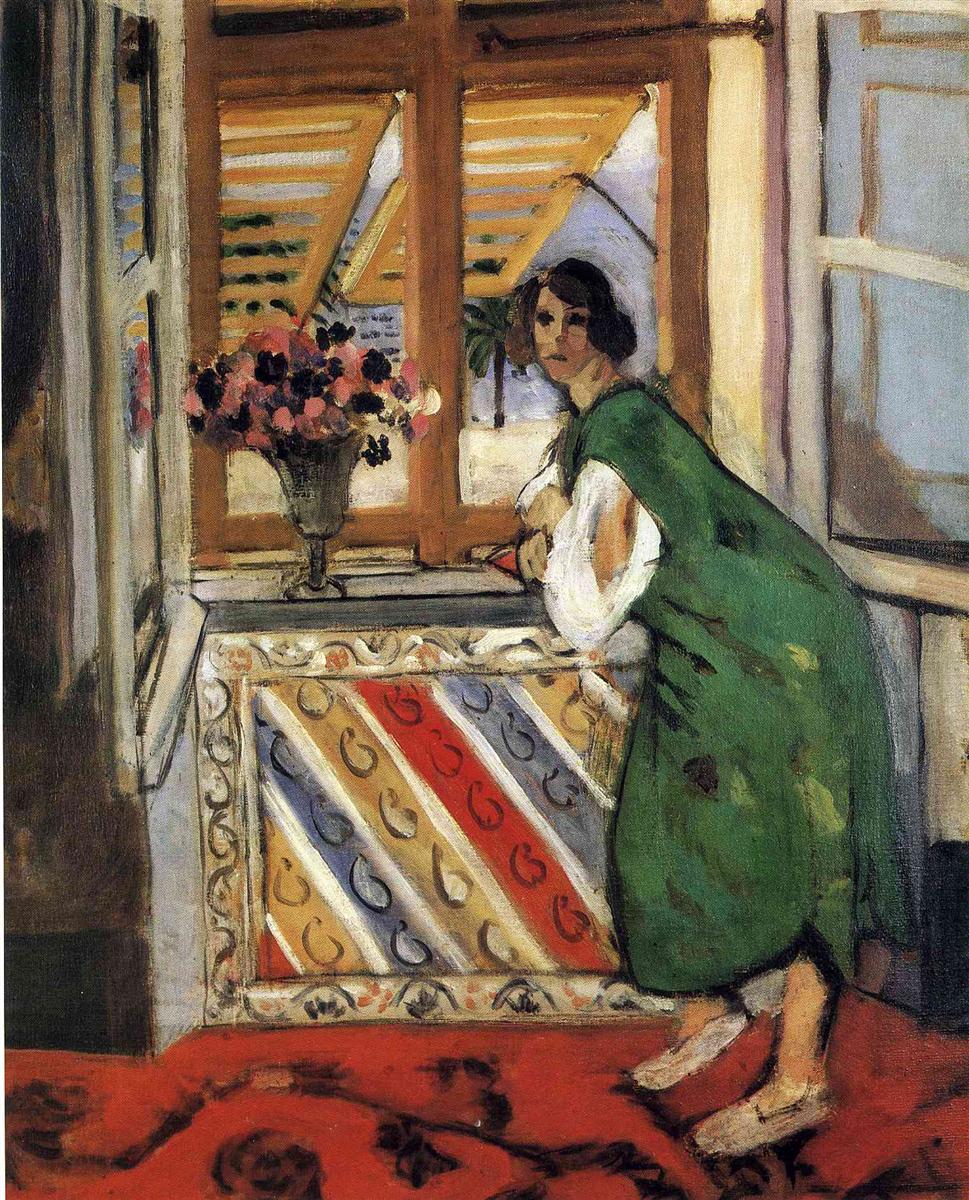

Henri Matisse’s “Young Girl in a Green Dress” is a poised dialogue between an attentive figure and a room tuned to color. A young woman leans into the sill of a wide window, her green dress acting like a living leaf inside a chamber of warm woods, patterned masonry, and a crimson carpet. Shutters tilt outside like golden blinds catching Mediterranean light; a vase of anemones anchors the sill; beneath the window, a decorative panel banded diagonally in blue, ochre, cream, and red hums with looping motifs. Rather than narrating an event, Matisse stages an atmosphere: the sensation of standing at a threshold where interior calm and exterior brightness meet.

The Nice-period idea of comfort and attention

Painted during the Nice years, the canvas participates in Matisse’s modern classicism, where the decorative is not an accessory but the grammar of the image. The subject is simple—looking out a window—yet the feeling is complex. Comfort is everywhere: the deep red carpet softens the floor; the sash of the dress drapes loosely; the shutters sieve glare into useable light. Attention, too, is everywhere: the woman’s weight rides forward onto her hands; the window framing disciplines the scene; the color chords are tuned so no passage shouts. This balance between bodily ease and visual concentration is the Nice period’s central promise, and this painting is one of its most concise proofs.

Composition: a theater of rectangles with a figure as hinge

Matisse organizes the picture as a set of nested frames. The room’s wall and floor define the outer field; the heavy window casing forms a second stage; the shutters beyond supply a third; the triangular scrap of sky and palm beyond hint at a fourth. The young woman occupies the hinge between these rectangles, her bent posture echoing the diagonal slats of the shutters and the stripes on the decorative panel. The vase sits where a center might be, yet the figure is purposely off to the right, allowing the flowers and patterned panel to counterbalance her mass. Nothing is centered dogmatically; the composition works by gentle asymmetries that make looking feel natural rather than posed.

Color climate: viridian, warm wood, and crimson ground

The palette is a measured chord. The dress’s viridian and bottle greens carry the chromatic melody; the window’s woodwork and shutters deliver warm ochres that modulate into honeyed yellows outside; the carpet saturates the base with a crimson field mottled by deep floral forms. The patterned under-panel repeats the climate in miniature, parading diagonal bands of blue, ochre, cream, and red, each dotted with small loops that keep the surface alive. Flesh is kept in a quiet register—peach warmed by reflected reds—so the figure sits among, rather than on top of, the room. Everywhere the paint stops early, letting the weave of the canvas and small value jumps provide glitter instead of heavy highlights.

The green dress as structural anchor

The dress is more than costume; it is architecture. Its long vertical mass counters the horizontal emphasis of sill, sash, and shutter. Its color registers the interior as a gardened space, connecting bouquet to palm beyond. Matisse handles the cloth with broad, breathable strokes, reserving darker seams to articulate weight at the hem and folds at the waist. The white blouse sleeves bubble from the armholes like puffs of air, cooling the green and repeating the vase’s pale blooms. A narrow black headband and dark hair supply small accents that keep the face legible against the glowing wall.

Drawing that conducts the eye without imprisoning it

Contour in this painting acts like a conductor’s baton. The window bars are set with deliberate, slightly wavering strokes that assert structure while admitting the hand. Around the figure the line thickens where the green meets the red carpet or the pale sill, then thins at the cheek and wrist to let light and value complete the forms. Curlicues within the decorative panel replace hard outlines; pattern draws the eye while the panel’s outer border, lightly brushed, keeps the tapestry from feeling glued on. The vase is almost not “drawn” at all—just a few decisive strokes for foot, belly, and rim—yet it sits solidly because value relationships are right.

Pattern as architecture

One of Matisse’s Nice-period inventions is to treat pattern as load-bearing. The diagonally striped panel under the window does the spatial work of a balustrade or radiator cover while contributing a metrical rhythm that electrifies the lower middle of the canvas. Its diagonal bands rhyme with the shutters beyond and the lean of the girl’s body, binding inside and outside. The carpet’s roses, dispersed and darker than the ground, anchor the base with a slow beat while preventing the red from reading as a flat poster field. The bouquet is the room’s treble: small pinks, whites, and deep centers, each a quick touch, never counted petal by petal. Pattern does not describe; it organizes.

Light distributed by relationships, not by spotlight

There is no single dramatic source of light. Illumination results from carefully tuned neighbors. The ochre shutters warm the window’s wood; their slats lighten where they catch the sky and darken where they overlap. The girl’s face turns into a half-shadow that remains luminous because it sits against the pale blouse and warm wood. The green dress brightens along edges that meet the sill and carpet, then drops to a cooler, darker register in its interior folds, where it takes back some of the carpet’s heat. The bouquet glows because its whites are saved for small planes and surrounded by cool and warm mid-tones. Light is thus a network of agreements rather than a diagram traced to a hidden sun.

The window as a measured threshold

Matisse loves windows because they let him stage transitions between color climates. Here, the interior’s reds, greens, and warm woods pass through a sieve of slats into a faint coastal blue. The triangular scrap of sky and a palm frond insert a Mediterranean whisper without forcing deep space. The sash bars are thick enough to be felt as objects and thin enough to act as musical staves on which the room’s motifs are notated. The girl’s body leans into this threshold; her gaze is outward, but the painting keeps us with her, inside—our enjoyment is mediated through color and framing rather than through a fully rendered exterior view.

The bouquet as chromatic hinge and emotional counterpoint

Placed slightly left of center, the bouquet provides a small theater of color relations. Pink and white flowers gather light, black centers punctuate, grey-green leaves cool the cluster, and the smoky metal of the vase stabilizes the group. Its scale is crucial: large enough to counter the figure, small enough not to become a competing subject. Psychologically, it serves as a companion to the girl’s outward gaze: a living thing at her elbow that belongs to the room, just as the palm belongs to the view.

Space built from stacked planes and overlaps

The room’s depth is shallow by design, constructed from stacked, readable planes: carpet, patterned panel, sill, window frame, shutters, and sky. Overlaps do the heavy lifting: the girl’s elbows ride the sill; her hip slides in front of the panel; the vase interrupts the sash; the shutters cut the sky. Because each plane is decorated—carpet pattern, panel loops, slat stripes—the eye never falls into blank distance. The effect is intimacy without claustrophobia, a room pressed pleasantly close around a thinking person.

Brushwork with air in it

Matisse’s touch remains visible. The carpet’s reds are pulled in wide strokes that leave small variations in saturation; the roses are laid on top in looser, deeper marks. The panel’s loops are painted quickly, sometimes with the brush’s end imprinting a dot, sometimes with the side scumbling a curve. The shutters show on their edges a slight unsteadiness typical of painting from life, which keeps the scene from hardening into diagram. Flesh is handled with short, turning strokes that allow warm and cool notes to mingle. Everywhere, he finishes early; the sensation of daylight depends on this visible breathing of paint.

Gesture and character without melodrama

The young woman’s character emerges from posture and placement rather than explicit expression. She stands in stockings, slightly pigeon-toed, a practical detail that humanizes the scene. Her elbows nestle into the sill, forearms relaxed, hands barely clasped—an alert yet unforced stance. The head tilts just enough to align with the shutter diagonals, and the gaze aims outward through a narrow slice of the world. Matisse avoids narrative flourish; he trusts that recognition of a lived posture—someone caught between contemplation and curiosity—will carry emotion.

The ethics of ease

Matisse’s desire to make pictures that provide calm is often misunderstood as an avoidance of seriousness. Here, ease is an achievement of proportion and clarity. The green of the dress could have dominated; it doesn’t, because the carpet grounds it and the woodwork warms it. The patterns could have shouted; they don’t, because their scale and density are calibrated to their roles. The figure could have felt staged; she doesn’t, because her weight, gaze, and relation to the sill are physically believable. The calm we feel is earned, not merely decorative.

Relations to other window pictures

“Young Girl in a Green Dress” belongs to a family that includes “Open Window, Etretat,” “Woman by the Window,” and “The Open Window.” Compared with the coastal vistas and balcony spread of some Nice interiors, this painting is more inward, the view restricted by shutters and framed by wood. It shares with its siblings the essential Matisse problem—how to make the decorative carry space and mood—but it resolves it with an especially concise set of means: one figure, one bouquet, one patterned panel, one red ground, one window. The economy clarifies how the parts cooperate.

The viewer’s circuit through the picture

The composition invites a repeatable route. Many viewers begin at the face, where warmer flesh meets the cool blouse. From there the gaze falls to the clasped hands and slides into the patterned panel, follows a diagonal band to the vase, climbs through flowers to the top of the sash, exits along the shutter slats toward the palm, then returns via the vertical window bar to the curve of the shoulder and the green dress. Each lap reveals small episodes—the thin grey seam that pins sill to wall, a sliver of blue beyond the shutter, the darkest rose on the carpet, a quick white highlight on the vase’s rim—renewing the image’s freshness.

Sensation over description

Matisse refuses literalism. The palm is a flick of green; the outside sky is a pale wedge; the flowers are notes of color rather than species. Yet we accept the scene because the relations are true: warm light through shutters, cool room air, a body at ease bridging both. The picture persuades through sensation—the right temperatures, the right weights—not through inventory. That is the secret of its longevity; sensation ages better than description.

Conclusion

“Young Girl in a Green Dress” is not a momentary snapshot but a composed climate. Pattern acts as architecture; color sets the weather; drawing conducts attention; brushwork keeps air moving; a single human presence binds interior and exterior. In this room, everything that could be merely ornamental becomes structural, and everything structural is tenderly ornamental. The painting offers a way of dwelling—alert, calm, suffused with light—that still feels contemporary, because it is built from relations that remain inexhaustible.