Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

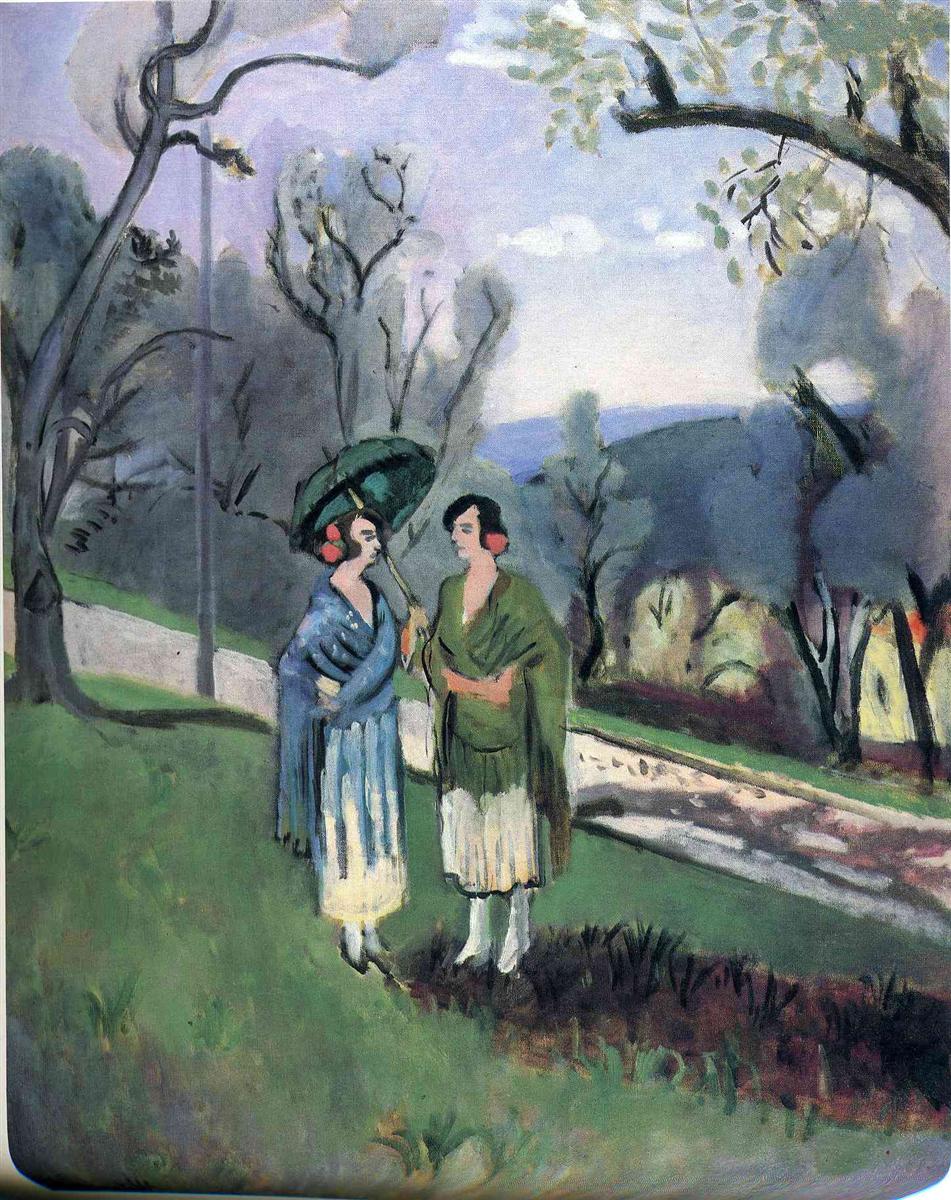

Henri Matisse’s “Conversation under the Olive Trees” captures a pause in the day when talk, shade, and moving air braid into one sensory experience. Two women, wrapped in shawls and modest dresses, meet on a grassy slope beside a pale path; one holds a green parasol, the other a walking stick or fan. Olive trunks and tapering branches arc above them like cursive lines, and beyond the figures a soft, blue-lavender distance lifts toward a sky streaked with cloud. Painted during Matisse’s Nice period, the canvas exchanges spectacle for poise: it organizes nature and human presence into a lucid harmony of color, line, and rhythm that feels at once intimate and expansive.

A Southern Motif Focused on Social Quiet

The Mediterranean landscape—its silvery trees, branching shadows, and humidity of light—gave Matisse a vocabulary for calm. Here he chooses not the seaside promenade or the hotel balcony but a path skirting an orchard. The title names the subject directly: conversation. This is not narrative drama; it is a social rite distilled to essentials. The women’s stance—one slightly forward, the other receptive under the parasol—implies exchange without theatricality. The grove becomes a listening room, its canopy a natural proscenium that frames the pause between sentences.

Composition Conducted by Curves and Cross-Rhythms

The picture’s architecture is a choreography of gentle curves. A pale path sweeps from upper left to lower right, separating the close green from the middle distance. The tilt of the slope establishes a slow diagonal that echoes in the women’s bodies and the leaning trunks. A strong, dark branch enters from the upper right, answering the tall, wiry tree at the left edge; together they form a parenthesis around the figures. The umbrella’s round top reprises these arcs in miniature and becomes a pivot for the entire scene. Nothing is centered dogmatically; instead, weight is distributed by counter-gestures—slope against branch, path against canopy, one figure’s verticality against the other’s slight contrapposto—so the eye moves in a relaxed loop rather than a march.

Color Climate: Olive Greens, Sky Lavenders, and Shawl Blues

Matisse sets the painting’s weather with a handful of tuned hues. The ground is a range of greens—sap, olive, and cool meadow—scumbled and glazed so the grass breathes. Tree foliage tends toward blue-green with silvery notes peculiar to olives, while trunks are not brown but a graphite mix of green-black and warm grey, anchoring the canopy without heaviness. The distance is a long chord of lavender and periwinkle that reads as heat haze over hills. Against this natural register he places human color: a blue shawl banded with white for the umbrella-holder, and a dull olive shawl for her companion. These garments converse chromatically with the grove around them—blue cooling the green, olive deepening it—so people and place are bound by color rather than separated by it.

Brushwork That Lets Air Circulate

The paint handling remains candid. Broad, semi-opaque strokes lay in the sky; translucent veils soften the hills; the grass is described with lateral pulls that accelerate and slow, leaving dry bristle marks like wind across blades. Trunks are drawn with fluid, calligraphic lines that thicken and thin, the mark of a hand rehearsed in arabesque. The figures are built from a few confident planes—shawl, dress, stockings, faces—then clarified by a supple contour. Everywhere Matisse stops as soon as each passage “reads.” This refusal to polish keeps the surface ventilated, and that ventilation becomes the sensation of moving air under trees.

Drawing as Conductor, Not Cage

Matisse’s contour is elastic, the opposite of a hard outline. Around faces and hands it thins so light can pass; along the umbrella’s stem and tree limbs it darkens and steadies to carry structure. The left-hand tree ascends like a musical staff, the line looping and separating, then recommitting as it meets a tuft of leaf. The umbrella’s arc is a single, confident sweep that cues our attention to the women’s exchange. The line conducts attention through the piece, indicating measure and tempo, then receding so color can sing.

The Path as a Ribbon of Time

The pale path is a practical motif and a temporal device. Bright against the greens, it guides the eye from upper left—where a distant light gathers—down to the figures and then away along the slope. We feel time passing as if we had walked from sun to shade ourselves. Its alternating bright and shadowed segments also measure the canopy’s density, translating foliage into a readable meter. In this way, a simple band of ground becomes the painting’s quiet narrative: approach, pause, continue.

Two Figures as Paired Tempos

The women are not anonymous mannequins; they propose two manners of attention. The umbrella-holder has a listening tilt, her head tucked under green shade; the other stands more upright, her hand poised in mid-speech. Their shawls—one blue, one olive—double the painting’s central color relationship, and their matching pale dresses and stockings link them as partners rather than opposites. Matisse humanizes them without over-modeling: a red ear muff or ribbon spot-warms each profile; a few shadow planes define cheek and chin. Their faces and gesture are sufficiently particular to suggest character, yet generalized enough to remain archetypes of social ease.

Light Distributed Through Relations

The light in this picture is everywhere and nowhere. There is no single spotlight; instead, values are tuned so that illumination arises from adjacency. Grass brightens next to the path; lavender hills glow by contrast with dark trees; shawls turn cooler or warmer depending on their neighbors. The umbrella’s underside is a darker green that throws the face below into a tender half-shadow, a small but decisive touch that makes the figure plausible inside the grove’s climate. Because the light is relational, it remains convincing even as forms are abbreviated.

Space Made from Stacked, Permeable Planes

Depth is achieved by layering, not by strict perspective. We stand on the near turf; the figures occupy a middle slab; the pale path slips behind them; a belt of trees builds the next plane; and, beyond that, hills soften into lavender. Each layer remains somewhat permeable—the trees’ interiors are airy, the hills’ edges diffuse—so the scene feels like a sequence of breaths rather than a stack of cardboard. This keeps the viewer close to the surface while granting enough distance to wander.

Pattern as Timekeeper in Nature

Matisse loved pattern in textiles; here he discovers pattern in the grove. The repeated verticals of thin trunks, the scalloped edges of foliage, the dotted light on the path, and even the tufted grasses at the women’s feet become natural ornaments. They are not decorative distractions; they are timekeepers. As the eye steps from trunk to trunk or tuft to tuft, it counts the grove’s rhythm, much as it would in a patterned carpet. The result is a pastoral that keeps time with the same grace as his interiors.

The Parasol as Pivot and Sign

The small green parasol performs three tasks. Visually, it is the painting’s pivot: a compact, emphatic circle among long curves and verticals that focuses the composition around the heads. Chromatically, it strengthens the dialogue between blue and olive by offering a deeper, cooler green that binds nature to costume. Symbolically, it names the activity: a leisurely walk under southern light, where shade is chosen rather than imposed. The parasol declares that conversation is the day’s work.

Echoes of Earlier Fauvism, Calmed by Nice Poise

The painting remembers Fauvism—the courage to let color carry structure, the frankness of the mark—but it softens the earlier heat into a Nice-period calm. Blues and greens are gentler, outlines more negotiable, forms more classically posed. The energy migrates from shock to measure. What remains from the wild years is the conviction that one can tell the truth of experience with a few tuned intervals rather than a mass of detail.

The Ethics of Ease

Matisse often spoke of offering viewers a “soothing, calming influence.” Here, ease is not inertia; it is a well-kept balance among elements. The slope invites but does not rush; the path leads but does not compel; the grove shelters but does not enclose. The figures cooperate with the landscape rather than dominating it. The painting models a humane rhythm for attention—alert yet unstrained—that the viewer can inhabit for a while and take away.

The Viewer’s Circuit Through the Scene

The composition invites a repeatable circuit. Most viewers enter at the parasol’s deep green, follow the exchange between faces, drop down to the tufted grasses at their feet, cross the path to the right-hand trees, climb the dark branch that arcs from the upper right, float across the pale clouds, and descend the tall left-hand trunk back to the figures. Each lap reveals new incidents: a lavender glint along the hillside, a sudden cool seam in a shadow, a sharp hook of twig carving sky, a warmer echo of red at the ear that keeps the faces lively. This is hospitality by design—the image always has another small pleasure ready.

Sensation Rather Than Description

Botanical accuracy is not the point; sensation is. Olive trees are evoked by the silvery modulation of green and the structure of their branching; the path is believable through temperature and value, not mapped gravel; the distance convinces because its color breathes thinly and recedes. The sum of these relations feels truer than any inventory would. Viewers recognize the day because the painting gives them the right conditions—shade, breeze, hush—to experience it.

Why “Conversation under the Olive Trees” Endures

The canvas lingers because its order seems inevitable once seen. Curves cradle the talk; a single path conducts time; colors of dress borrow from colors of place; drawing guides without fencing; brushwork keeps air moving. Nothing clamors, nothing slackens. You leave with the memory of cool shadow on a warm afternoon and the contentment of a shared pause—the kind of small human dignity Matisse devoted a career to preserving.

Conclusion

“Conversation under the Olive Trees” is a model of modern classicism: a few elements—slope, path, grove, two figures—arranged with such tact that they produce an environment for attention. Color makes the climate, line sets the tempo, and brushwork keeps the scene permeable to air and feeling. The painting asks little and offers much: a place where talk can bloom under shade, where nature and sociability keep each other company, and where viewers can rehearse their own quiet conversations long after they leave the gallery.