Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

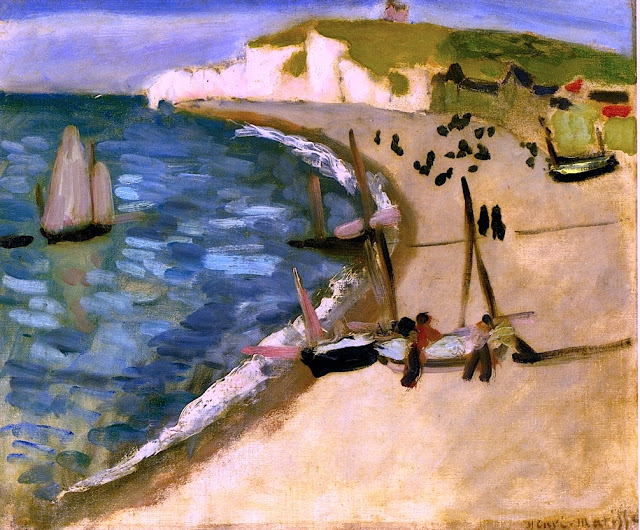

Henri Matisse’s “Yaht Amont Cliffs at Etretat” distills the drama of Normandy’s coast into a few decisive bands of color and a rhythm of angled masts. The shoreline sweeps in a long, pale arc; surf flickers in a thin scallop of white; green headlands terminate in chalk cliffs that catch the light like bone; and a bright, workaday beach hosts boats, poles, and small groups of figures. The sea itself is a mosaic of turquoise, teal, and slate, its restless tessellation set against the steady geometry of the beach. With extraordinary economy—broad passages, abbreviated forms, and a living contour—Matisse composes not a tourist view but a lesson in seeing: how a coast breathes when wind, water, and human labor share the same air.

A Normandy Motif Reimagined

Etretat, with its famous chalk arches and needles, had already been painted by Courbet, Monet, and a lineage of coastal painters who stressed either geologic spectacle or optical shimmer. Matisse arrives and simplifies. He chooses not to plant the viewer on a promontory facing a cathedral of rock. Instead he lowers the vantage slightly and turns the composition so that the sea’s slanted edge and the long sweep of sand become the principal actors. The cliffs remain—white, luminous, undeniable—but they serve the flow rather than interrupt it. This shift turns grandeur into tempo: the coast becomes something the eye can walk, not simply admire from afar.

Composition: One S-Shaped Coastline and a Lattice of Masts

The structure of the painting is lucid. An S-shaped boundary separates water from land, beginning at the lower left, dipping inward at mid-distance, then curling back toward the cliffs. That serpentine edge, scalloped by surf, conducts the gaze from foreground to horizon. Punctuating this curve is a sparse lattice of masts, spars, and poles driven into the beach. Their angled uprights syncopate the shoreline’s glide, providing beats that keep the eye from sliding too quickly along the sand. At right, the beach opens into a wide field of light; scattered groups of figures—inky commas—punctuate that field and establish human scale. The headland’s green mass and the signature white cliffs crown the upper right, while a band of soft sky closes the top.

Color Climate: Chalk, Sea-Glass, and Sand

Matisse’s palette is remarkably restrained: sea-glass blues and greens for water, creamy chalk for cliffs and surf, cool violet shadows within the sea’s mosaic, and warm buff for the beach. Each range is modulated, not multiplied. In the water, horizontal drags of teal, cyan, and blue-grey mingle, their edges kept visible so the surface glints and breathes. The surf is delivered as a narrow, crisp band—almost a single, continuous gesture—lightly scalloped to convey break and spill. The cliffs are painted in warm whites with ochre undertones that keep them sunlit rather than icy. The beach is a luminous sand color that deepens where damp and lightens where dry, creating the impression of a vast, gently sloped plane. Spot notes—brick red on a shed roof, deep green along the headland, black vessels pulled high—add punctuation without clutter.

Brushwork: Candor Over Finish

Everything here is decided with as few strokes as possible. The sea’s surface consists of broad, side-brushed rectangles whose slight overlaps leave a mosaic seam; these seams act like miniature wavelets without ever becoming literal. The surf’s edge is a dragged stroke that lets the canvas’s tooth pick up paint unevenly, a technique that reads as foam. The cliffs are blocked in with opaque, buttery touches and then edged with a thin, darker seam that separates rock from sky. On the beach Matisse uses thinner paint, letting the ground breathe through so the plane remains bright and quick. The masts are ink-like lines pulled in single movements. Figures are a handful of dabs, each one carefully placed to keep the crowd lively but light.

Space Without Pedantry

Depth is built from overlapping planes and value steps rather than from a plotted vanishing point. The beach widens toward the right foreground, tilting up subtly—Matisse’s familiar device for turning the ground into a welcoming stage. The masts recede by size and value, not by ruler; the posts further back are thinner, paler, and their bases softer, so the eye reads distance without measuring it. The cliffs occupy a bright, middle-distance bar whose upper contour undulates and whose lower edge is felt through the contrast with sea. Because everything is arranged as a layered set of simple fields, the image remains modern—flat enough to be honest, spacious enough to walk into.

The Sea as a Slow Mosaic

A distinct pleasure of this canvas is the sea’s treatment. Rather than annotating waves, Matisse sets down a field of subtly different tiles of color. They are rectangular, oblong, sometimes feathered, sometimes sharp, always lateral. This mosaic breathes across the surface like scales on a living body. Near the shore the rectangles lighten and thin, vibrating against the surf; farther out they darken and settle. The method conveys both texture and perspective: the “tiles” compress toward the horizon, suggesting depth without drawing it. It’s a brilliant compromise between description and abstraction—water as pattern, yet unmistakably water.

Boats, Poles, and Work

The angled poles and beached boats introduce the human economy of the place. These are not yachts at anchor in a postcard cove; they are working craft hauled up on pebbled sand, slung to poles, tended by people whose tiny, efficient silhouettes supply scale. Matisse suggests hulls with a few shapes—white inside, dark outside, their shadows pinning them to the beach. The poles tilt in different directions, like note stems in a score, breaking the monotony of beach light and letting the figure cluster read as activity rather than ornament. This infrastructure of labor gives the composition backbone and keeps the coastal lyric grounded.

The Cliffs: Light, Mass, and Memory

The famous Etretat cliffs—Amonte to the east, Aval to the west—often take center stage in paintings of the area. Here they are strong but not tyrannical. Matisse states them as a long, bright mass whose top edge breaks into the sky with a slow, toothy rhythm. A few warm shadows articulate ravines and a chapel-like structure atop the ridge. Their whiteness acts as a reflector, bouncing light down onto the sea’s edge and up into the sky’s undersides. They are geology, yes, but in Matisse’s telling they are also a light machine, completing the painting’s climate.

Figures as Tempo and Scale

Those scattered ink notes of people on the beach are vital. Without them the coast might read as a small cove seen from close up; with them, the breadth of the shore and the size of the cliffs become legible. Matisse places the groups in a loose procession that recedes with the shoreline, their distance marked by size diminution and fading contrast. Two larger figures near the boat in the right foreground arrest the eye briefly before releasing it toward the middle distance. Their posture and placement make a hinge between human and coastal scale—a simple, deft way to keep our attention inside the picture’s loop.

The Sky as Ceiling, Not Spectacle

The sky is handled with a few horizontal sweeps of pale blue and warm violet, thickened just enough to describe a ceiling of air. There is no cloud theater here; the sky’s job is to hold the light and to echo the water’s lateral rhythm. Near the horizon, a faint rose seam warms the junction of cliff and sky, a subtle counterpoint to the sea’s cools. The restraint keeps the composition from splitting into two competing dramas (sea vs. sky) and preserves the beach’s primacy.

Rhythm and the Viewer’s Path

The painting encourages a repeatable circuit. Many viewers enter through the surf band at the bottom left, slide along the water’s bright lip, hop from mast to mast across the beach, pause at the working figures and boats, then climb the headland to rest on the chalk cliffs. From there, the eye drifts along the horizon, across the soft sky, and re-enters the sea’s mosaic, where the rectangles lead back to the starting point. Each lap discloses small incidents—the violet cuff at a wave’s edge, a knife-like shadow cast by a pole, a dab of red roof catching sun, a dark form offshore that may be a rock or buoy. The picture’s hospitality lies in this steady, replenishing loop.

Sensation Over Description

A hallmark of Matisse’s Nice-period landscapes is their commitment to sensation rather than inventory. “Yaht Amont Cliffs at Etretat” exemplifies that ethic. No pebble is counted, no rigging diagrammed, no chalk stratum plotted; yet one feels wind, slope, glare, and distance. The success depends on relational truth: warm against cool, thin paint beside thick, horizontal drift set against diagonal thrust. The painting persuades not by telling us everything but by giving the eye the right conditions in which to recognize the coast.

Dialogue With the Impressionist Coast

Matisse’s treatment converses with Monet’s serial cliffs at Etretat. Where Monet multiplied moments and saturated the air with broken light, Matisse condenses. The sea becomes a mosaic, the beach a single sand plane, the cliff a bright mass, the human activity a sequence of marks. The difference is not a repudiation but an evolution toward modern classicism—fewer parts, clearer relations, equal freshness.

The Ethics of Ease and Work

Matisse often said he wanted his art to be a “good armchair” for the spirit. Even in a working harbor scene, he keeps that promise. Ease, here, is not idleness; it is a correct adjustment between elements. The boats rest where they ought to; the figures move with purpose; the shoreline carries them along; the cliff holds the light; and the sea’s mosaic breathes steadily. The result is calm without stillness, activity without noise—a poised balance that feels earned.

Why the Image Endures

The painting lasts in memory because its order feels inevitable. A single sweeping edge organizes everything, masts counterbalance the curve, the cliff crowns, the sea breathes, and the beach opens like a room. You can revisit it and find the same rightness waiting, along with new small pleasures: a cool seam along the surf, a green flare on the headland, a darker rock anchored in the water’s patchwork. The simplicity is generous, not spare; it leaves room for the viewer’s own seaside memories to resonate.

Conclusion

“Yaht Amont Cliffs at Etretat” shows Matisse at his most lucid: a coastal world reduced to essentials and animated by touch. The sweep of the shore, the tiled sea, the bright cliff, and the measured activity on the sand cooperate to produce a clear, durable calm. In place of spectacle he offers pace; in place of detail, relations; in place of rhetoric, a lived climate. It is not just a picture of Etretat; it is a way of feeling a shore.