Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

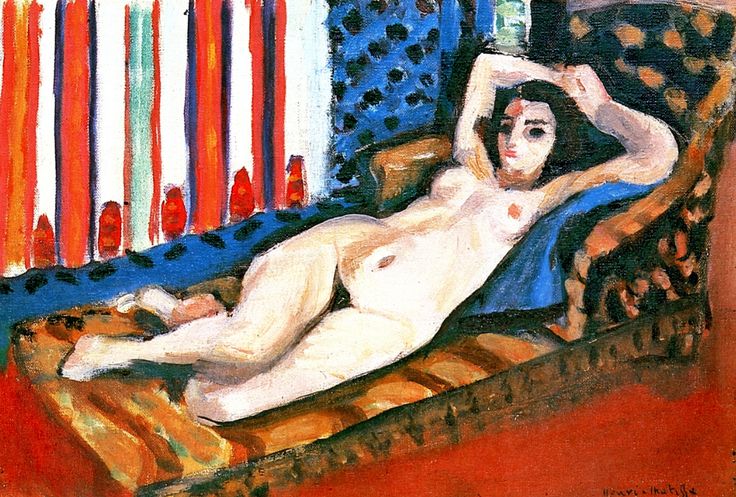

Henri Matisse’s “Nude on a Red Couch” stages a concise encounter between the living body and the living room—flesh reclining on patterned upholstery, a curtain banded with color, and a wall pricked with dark motifs. The model stretches diagonally from lower left to upper right, one arm resting behind the head, the other arcing above the brow. A wedge of blue cushion braces her back while the ochre-and-umber couch receives her weight. Around that central diagonal, Matisse composes a climate of red floor, patterned wall, and striped curtain that turns repose into a visual chord. Nothing in the scene is overexplained, yet everything is emphatically present: the contour is decisive, the paint is frank, and the color is tuned so that the room feels warm but breathable. The picture belongs to the Nice interiors that dominated Matisse’s early 1920s practice, but it carries a special, almost theatrical intensity because the figure is placed against saturated décor that insists on her aliveness.

A Nice-Period Interior Where Color Becomes Climate

By the early 1920s Matisse had exchanged the explosive chroma of Fauvism for an art of balance in which color behaves like air—pervasive, structural, and calm. The Nice rooms offered him a laboratory for that search. Their furnishings were modest but textural: chaise longues, patterned curtains, woven carpets, and a small vocabulary of props. In this painting, the décor does more than set a scene; it establishes a climate within which the figure can exist without melodrama. The red floor lifts warmth from below, the dotted wall cools the middle register, and the vertical bands of the curtain filter daylight. The figure, although nude, does not dominate by shock; she inhabits the climate as naturally as a person inhabits weather.

Composition Built On A Single Diagonal And Three Counterweights

The composition is anchored by the body’s long diagonal. That diagonal draws the eye from the model’s feet in the lower left, across the hip and abdomen, to the raised arm in the upper right. Matisse counters the thrust with three stabilizers. First, the couch’s long rectangle, slightly tilted, provides a platform whose front edge clips the lower frame and anchors the figure to the room. Second, the vertical bands of the curtain rise along the left edge, pushing back against the diagonal and offering a visual cadence. Third, the dotted wall forms a shallow, even field that prevents the figure from floating. These counterweights allow the diagonal to feel relaxed rather than precarious; the body can stretch without threatening the picture’s balance.

Pattern As Structure Rather Than Ornament

Pattern is the room’s skeleton. The curtain’s vertical stripes—brick red, coral, and off-white—act like organ pipes, establishing a measured beat that keeps the left edge active. The wall’s dense, dark dots create a second pattern at a smaller scale, a cool murmuring texture that absorbs light and frames the body without drawing attention to itself. The couch upholstery, flecked with ochre motifs, supplies a third pattern that sits closest to the skin and reads as touch. None of these motifs is fussy; Matisse paints them with quick, confident marks. They do crucial engineering: the stripe organizes, the dot cools, the flecked upholstery stabilizes weight.

Color Climate: Red, Ochre, Blue, And Flesh

The palette is economical and decisive. Red dominates the floor and detours up the curtain, ochre warms the couch, blue cools the cushion and slips into shadows along the wall, and flesh tones occupy the central passage. The red is not a single note; it spans from a vermilion floor to warmer brick in the curtain tails. The blues are equally nuanced, graying out at the wall and flashing pure on the cushion so the figure’s back reads against something cool. The ochres are inflected by umber and black, preventing the couch from becoming a flat, decorative bar. Flesh tones are built with pale coral, ivory, and a touch of lilac shadow. The total effect is harmonious rather than high-keyed: the room glows, but the air still circulates.

The Nude As Axis Of Poise

Matisse renders the model with an honesty that neither idealizes nor dramatizes. The contour is decisive around shoulder, breast, hip, and knee; it relaxes at the abdomen and along the forearm so the body can breathe. The face is a small theater of marks—dark almond of the eye, quick wedge for the nose, rose in the lips—enough to register attention without demanding narrative psychology. The left leg crosses loosely over the right, giving the diagonal a soft kink and signaling rest rather than display. One arm frames the head like a canopy, the other arcs behind the brow; these gestures echo the room’s architecture, converting the figure into an elegant structural member within the interior.

The Living Contour As Conductor

Line in this painting is not cage but conductor. It thickens along the couch’s edge, where structure demands clarity; it thins along the inner edge of the arm, where light should pass. Around the feet and hands the line grows calligraphic, delivering quick intimations of toes and fingers without counting them. Along the face it firms up again, clarifying features so the small head can sustain attention within the large field of color. This breathing contour organizes the painting’s rhythms; it cues entrances and fades, allowing color to sing while keeping the ensemble coherent.

Light Distributed Like Air

There is no single spotlight; illumination arrives by relationship. The red floor brightens around the couch’s front edge; the dotted wall carries cooler light that softens near the cushion; the curtain’s pale stripes imply daylight filtering through fabric. Across the figure, highlights pool where bone or tendon sits near the surface—the shoulder cap, the knee, the top of the foot—while shadows turn lilac rather than brown, preserving the flesh’s luminosity. Small accents—a brighter spot on the collarbone, a pale edge along the thigh—register the body’s structure with minimal means. Because light is distributed rather than staged, the room feels inhabitable and the body present.

Space And Depth Without Pedantry

Depth is created through overlap and value change rather than a strict perspectival box. The couch overlaps the red floor; the blue cushion overlaps the wall’s dotted field; the curtain overlaps the wall at left. The floor tilts gently toward the viewer, a Nice-period hallmark that turns the space into a welcoming stage rather than a receding tunnel. The result is a coherent interior that still honors the flatness of the painted surface. We can believe the room, yet we are never asked to forget that it is paint arranging color and line.

The Psychology Of Repose

Although the subject is a nude, the mood is not erotic display but composure. The model’s gaze meets us without anxiety; her body occupies the couch as if habitually at ease. The red floor and striped curtain inject energy, but the dotted wall and blue cushion temper it, so the scene settles into calm. Matisse once said he wanted his art to be “a soothing, calming influence on the mind, something like a good armchair.” The line and color here pursue exactly that: the armchair is literalized as couch, but also present as compositional comfort—everything placed where it can rest.

The Couch As Stage And Resonator

The ochre couch is both setting and instrument. Its warm color resonates with the red floor, enriching the lower register of the painting, while its dark seams and rolled arm articulate the figure’s placement. The diagonal of the cushion mirrors the diagonal of the body, and the blue backrest supplies a cool counter-beat that keeps the figure from sinking into warmth. Because the couch sits so close to the picture plane, it implicates the viewer’s body: we are not spying from a distance; we are near enough to feel the softness under the model’s arm.

Curtain And Wall As Rhythmic Partners

At the left edge, the banded curtain acts like a metronome—its verticals marking time against the horizontal couch and diagonal body. The tiny red teardrops at the stripe bases keep the rhythm playful and prevent the stripe from becoming purely architectural. Across the wall, the small dark dots whisper a counter-rhythm at a finer scale, cooling the room and giving the eye a place to idle without fatigue. Together, curtain and wall establish a visual soundtrack that supports the figure’s long melody.

Brushwork And The Evidence Of Decisions

Matisse paints decisively and stops early. The floor is laid with broad, quick sweeps that leave slight ridges—paint behaving like a woven surface. The dots of the wall are dabbed and dragged, so they vary in shape and pressure and never congeal into a printed pattern. The curtain stripes are pulled with a loaded brush; at their edges, bristles splay, letting the ground breathe through. Flesh is thinner, often scumbled, so the canvas’s tooth contributes to the skin’s liveliness. This economy of touch allows the painting to feel freshly made, its decisions legible and confident.

The Viewer’s Circuit Through The Image

The composition proposes a repeatable path. Many viewers begin at the face, slide along the raised arm to the right edge, descend the outer contour to the hip, cross the abdomen, and continue to the crossed feet. From there the eye steps onto the couch’s front edge, travels along the red floor to the banded curtain, rises through the stripes, and returns across the dotted wall to the face. Each lap reveals new incidents: a darker wedge where arm meets cushion, a small blue echo along the ribcage, a glint of white at the toe, a sliver of greenish light at the top of the curtain. The picture is built for this looping attention—calm, steady, and inexhaustible.

Dialogues With Sister Works

“Nude on a Red Couch” converses with other Nice-period odalisques and interiors. Compared with the more elaborate rooms of later 1920s canvases—thickly patterned carpets, brocaded screens, exotic costumes—this painting is relatively distilled: a single couch, one curtain, a dotted wall, and a red floor. Compared with the earlier Fauvist nudes, the palette is moderated and the drawing more controlling; the body is not a field for color explosions but a center of gravity that calibrates the room. The continuity across all these works is Matisse’s grammar: large simple shapes, measured color chords, and a breathing contour.

Sensation Over Description

The painting communicates by sensation rather than by catalog. We feel the coolness of the blue cushion against skin, the soft give of the couch under the hip, the dry warmth of the red floor, the slight draught near the curtain. None of this is rendered through descriptive detail; it is achieved by placing colors and edges in right relation. The body convinces not because muscles are drawn but because pressure points, highlights, and shadow temperatures are true to experience. The décor convinces not because every motif is counted but because the patterns move at tempos the eye believes.

The Ethics Of Comfort

A recurring theme in Matisse’s interiors is the dignity of comfort. Comfort in this sense is not indulgence; it is a balance of forces that allows a person to rest without collapsing, to be present without posing. The red couch supports the figure; the curtain filters light; the wall absorbs glare; the palette steadies nerves. The painting becomes, in itself, a kind of furniture for the mind—an arrangement of relations that invites composure.

Why The Image Endures

The picture lasts in memory because its order feels inevitable once seen. The diagonal of the body, the rectangular couch, the vertical stripes, the dotted field, and the red plane interlock with clarity. The palette is limited but full; the brushwork is candid; the contour is alive. You can return to it repeatedly and find the same rightness waiting—the sensation of a room expertly tuned to hold a human presence.

Conclusion

“Nude on a Red Couch” is a chamber piece in color and line. The red floor keeps time, the curtain marks the measure, the dotted wall hums a cool drone, the ochre couch resonates, the blue cushion provides countermelody, and the figure carries the theme in a sustained, unforced diagonal. Matisse proves that simplicity—chemically pure intervals of color, a few confident edges, and an uncluttered set—can deliver a complex, durable calm. Nothing shouts, yet everything is emphatic. The result is a modern classic: intimate, poised, and luminously at ease.