Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

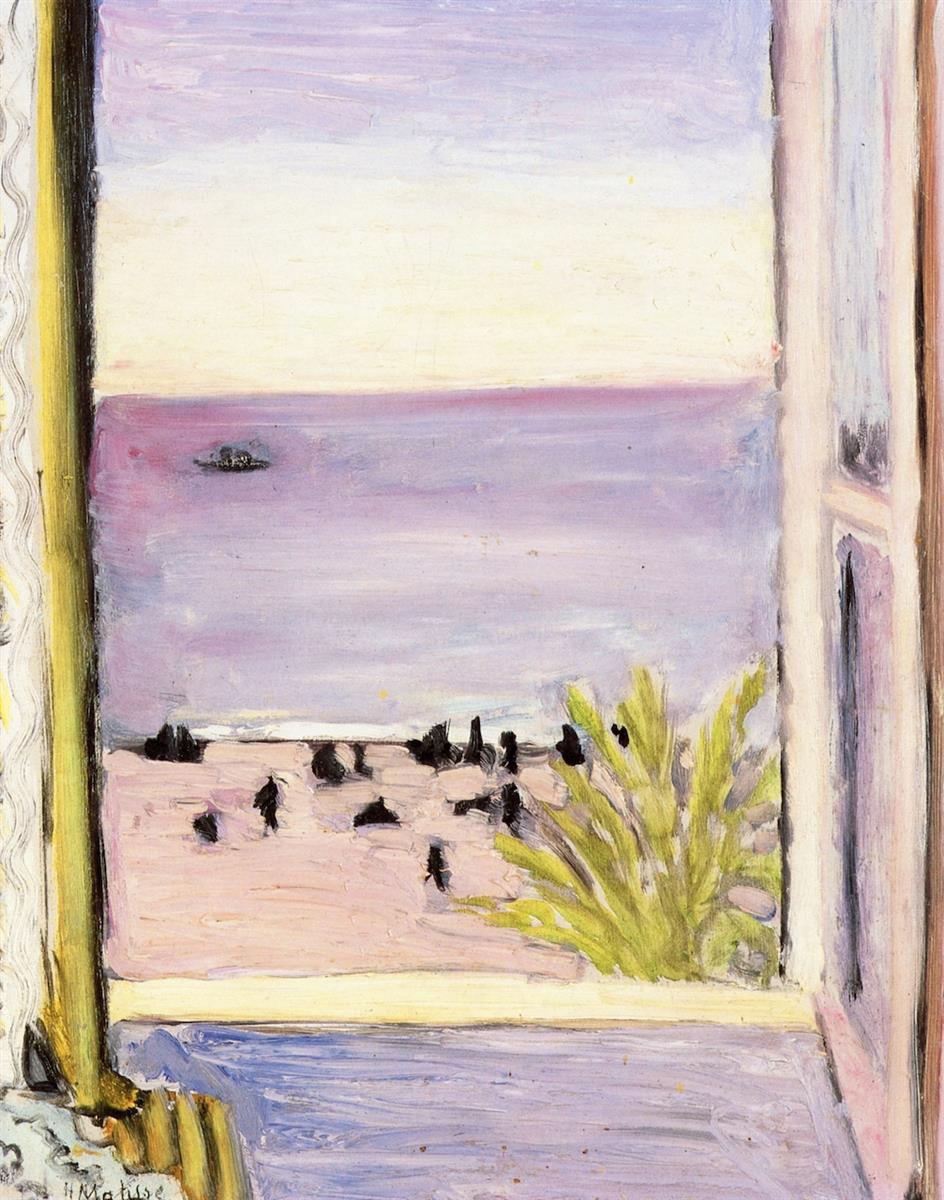

Henri Matisse’s “The Open Window” presents the Mediterranean not as a postcard but as a breath of light moving through a room. We stand in the threshold, between a pale interior and a banded horizon where lavender sea meets a bright, lemon-cream sky. A sliver of balcony or sill anchors the foreground; a tuft of sunstruck greenery rises at the right edge; and tiny black notes—people and parasols reduced to essentials—scatter across the beach. The composition is spare, but not empty. With a few tuned colors and an elastic contour, Matisse composes a scene in which looking out becomes the subject itself, and the window is both a literal opening and a way of thinking about painting.

A Nice-Period Window Onto Calm

Painted during the Nice years, this canvas belongs to Matisse’s pursuit of modern classicism after the experimental upheavals of the 1910s. In these interiors he turned from fauvist blaze to climate: color became atmosphere; pattern became structure; line became a conductor that held shapes in a poised ensemble. The open window is a central motif of that project because it lets inside and outside act upon one another. The sea’s cool bands enter the room and soften its whites; the room’s pale edges frame the view and make it legible. The image is not a landscape observed from afar but a shared environment where air passes freely across the threshold.

Composition As Two Uprights And A Horizon

The design is anchored by three dominant elements: the two vertical posts of the window and the long horizon line where sea meets sky. The verticals stabilize the field like pillars, while the horizon supplies a calm bar that organizes color into horizontal registers. The lower band is beach, the middle is sea, and the upper is sky, each with its own modulation of lavender, rose, and cream. The plant at right interrupts those registers with a small burst of diagonals, preventing the view from becoming too serene to hold. A strip of interior floor in the foreground tilts gently upward, making the window’s threshold legible and establishing a close place for the viewer’s body.

The Window As Device, Not Just Motif

For Matisse, the window is a pictorial machine. It provides a frame within the frame, a chance to contrast the slow breathing of exterior bands with the tactile edges of interior wood and plaster. The left jamb, brushed in yellow-ochre with a softly dark inner seam, reads as a sunwarmed edge; the right jamb is cooler and lilac-toned, suggesting shade. Between them the view is not a hole but a plane that presses gently forward, like a sheet of light. The window thus becomes a hinge: not a hole cut into the painting, but a surface that converses with the room.

Color Climate: Lavender, Lemon, and Sea

The palette is remarkably restrained. Lavender carries most of the weight, sliding from bluish-violet in the water to rosier tints along the beach. Above, a pale lemon light spills into a near-white sky that warms at the horizon. These temperatures are held in balance by the window’s cool lilacs and the warm yellow left edge, so the total climate feels breathable rather than sugary. Black appears only in small, decisive notes—the silhouettes on the beach and a tiny boat at sea—providing punctuation and scale. A spring-green clump of foliage at right serves as the painting’s brightest accent, a little burst that ties the exterior to the touchable world of leaves and wind.

Light Distributed Like Air

There is no single theatrical light source. Illumination in the picture is relational: interior edges brighten next to dark seams; the beach lightens where it meets the sea; the sea deepens where it turns away from the sun; the sky opens to a thin wash of warm white. The small wedge of foreground floor, brushed in cool violet, lets us feel reflected light from the water entering the room. Highlights are minimal but meaningful—a tiny spark on the boat, a few pale specks in the foliage—so the painting keeps its calm while remaining alive.

Edge, Contour, and the Tender Frame

Matisse often speaks through edges, and here the edges carry the mood. The left curtain’s scalloped inner line undulates like a slow breath, softening the architectural post beside it. The internal edges of the right-hand window frame are slightly wobbled; they are painted rather than drafted, reminding us that space here is made by hand. Even the horizon is not a ruler-straight razor; it is a narrow zone where colors meet and fuse, the way sky and water exchange brightness in noon glare. These gentle edges keep the view from turning hard or distant; they bring the scene into the sympathetic proximity of a room.

Brushwork and the Evidence of Seeing

The surface tells the story of decisions. Broad, horizontal passes build the sea; thinner, vertical licks articulate jambs and curtains; small, calligraphic touches invent beachgoers, trees, and the tiny boat. Matisse stops each passage as soon as it “reads.” The beach figures are a handful of commas; the plant is a few hooked strokes of yellow-green; the curtain is a wavy border and a pale field. The candor of the touch is part of the pleasure. Rather than smothering the panel in polish, he lets the viewer share the quickness of recognition: this stroke is water; that one, grass; this seam, a frame; that speck, a person in sun.

Space Without Pedantry

Depth arises from overlap and value steps, not from linear perspective. The interior floor overlaps the sill; the sill and jambs overlap the beach; the beach overlies the sea; the sea continues to the horizon and meets the sky. The plant interrupts the overlap and anchors the right edge so the view does not float. Because each plane is treated as a field of color with its own rhythm rather than a receding grid, the painting can remain modern—flat enough to be honest, spacious enough to let the eye travel.

The Sea as a Quiet Pulse

The sea is not rendered wave by wave; it is a slow modulation of violet and blue, thickened here, thinned there, with an occasional horizontal drag that reads as swell. That restraint gives the water the dignity of a pulse. It beats under the scene and sets the tempo for the whole painting. The tiny boat, placed just off-center, answers like a single note above a drone. Because the sea is painted as a continuous field, it holds the eye softly and prevents the composition from breaking into scattered incidents.

The Beach as Human Scale

Those small black marks along the beach carry more than narrative. They are the scale against which the window’s size and the sea’s breadth become legible. Without them, the horizon could be a small lake seen from close up; with them, the view opens into proper distance. They also contribute to rhythm: irregularly spaced, they prevent the bands of color from becoming monotonous and quietly echo the scallops of the interior curtain.

The Plant as Pedestal of Life

The pale, lemony bush at the right edge is more than a decorative flourish. It is the most tactile thing in the picture—the place where exterior nature kisses the touchable world of interior architecture. Its color ties to the warm left jamb, making a chromatic bridge that pulls the sea’s coolness into the room. Formally, its diagonals counter the painting’s horizontals, adding a small, necessary turbulence to a view otherwise smoothed by light.

The Interior Floor as Threshold

The sliver of violet floor at the bottom is crucial to the painting’s hospitality. It gives the viewer footing and confirms that this is an experience of looking-from rather than a placeless view. Its cool, brushed plane carries reflections from outside and reminds you that light has entered the room before it touches your eye. It is also a structural clamp that holds the vertical jambs in place, completing the window’s inner frame so the picture does not dissolve into a floating landscape.

Sensation Over Description

The power of “The Open Window” lies in how it transfers sensation rather than inventory. You feel the quiet glare of late morning, the way air flattens near water, the hum of distant figures, the stillness of a room breathing with the sea. None of this arrives through detail. It arrives through relations—warm beside cool, thick paint next to a thin wash, a steady horizon held between two hand-painted uprights. Matisse trusts the eye to complete what he proposes.

The Viewer’s Circuit Through the Image

The picture encourages a looped path that never hurries. Many viewers enter through the plant or the bright left jamb, descend to the cool floor, jump across the sill to the pale beach, and then drift out over the sea to rest on the horizon before returning to the interior edges. Each lap discloses another small incident: a wavering seam in the frame, a brighter slip of pigment near the waterline, a tiny spark on the boat’s cabin, a lighter touch at the curtain’s scallop. The painting is built for revisits; its simplicity is a surface over deep, repeatable seeing.

Kinships with Sister Windows

Matisse returned to open windows often, from early Fauvist years to Nice-period interiors. In some canvases, the window frames a bustling harbor or a table set with flowers; in others, it stages a dialogue between inside patterns and outside bands of light. This version is among the most distilled. Furniture is absent; the room reduces to frame and floor; the view reduces to sky, sea, sand, and a tuft of life. That reduction clarifies the theme: the grace with which a room can hold an expanse.

A Modern Classicism

The painting achieves a modern classicism by reconciling flat design with the felt world. The bands of color and the shaped frame could belong to an abstract composition; the tiny people, the boat, and the breeze-tossed plant insist on a lived place. The union is effortless: clarity without chill, atmosphere without vagueness. Even the signature curls into the foreground like a reminder that the scene is not merely there; it is made, and made with pleasure.

Why the Image Endures

“The Open Window” lingers because it captures the moment before narrative begins. Nothing “happens,” yet everything breathes: room, sea, light, air. The eye never snags on trivia or gets lost in emptiness. Instead it rests on a horizon that promises return and on edges that feel drawn by a steady hand. You can carry the picture around the way you carry a sentence that says exactly what it means with almost no words.

Conclusion

Matisse offers a window that is also a way of looking—an invitation to stand at a threshold where interior poise and exterior radiance keep one another company. Two uprights, one horizon, a plant, a floor, a handful of silhouettes, and a boat are all he needs to orchestrate a calm that feels earned. The painting is not about escaping the room; it is about letting the world in until room and world share the same light. In that shared light, the act of seeing becomes a quiet form of happiness.