Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

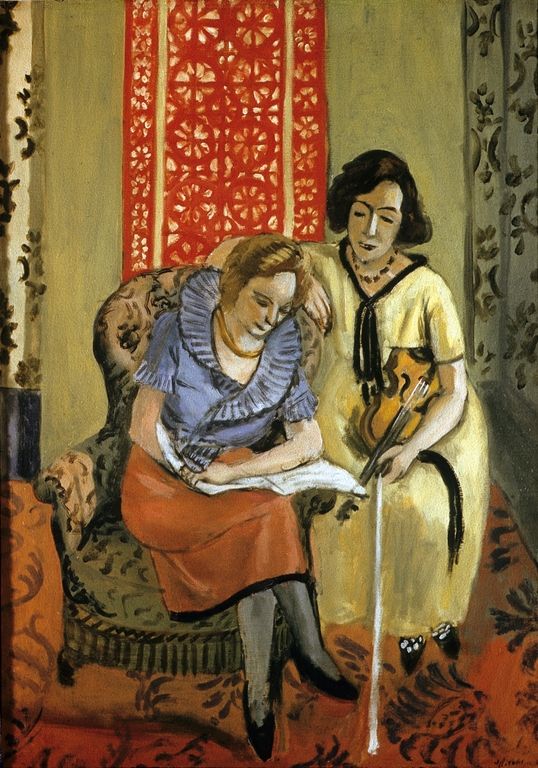

Henri Matisse’s “Musicians” draws a circle of intimacy around two women in a room tuned to color and pattern. One figure sits in an overstuffed armchair, head bent over a sheet of music; the other, standing at her side, cradles a violin and bow. A red-orange carpet, vegetal wall textiles, and a dazzling strip of cut-paper–like ornament at the center supply a visual orchestra that supports the quiet duet between concentration and companionship. Matisse does not present a spectacle of virtuosity; he stages an atmosphere where music, looking, and living share the same air. The painting belongs to the constellation of Nice-period interiors in which the artist refined an art of balance: chroma tempered into climate, contour used like a conductor’s baton, and domestic space treated as a humane architecture for attention.

A Nice-Period Interior Tuned to Listening

“Musicians” crystallizes the ethos of Matisse’s early 1920s practice. After the pyrotechnics of Fauvism and the structural testing of the 1910s, he returned to rooms flooded with Mediterranean light and furnished with thick textiles, curving chairs, and modest instruments. In these works, comfort is not a retreat from modernity; it is a modern value. Music enters naturally. Instead of the concert hall’s glare, we are in a salon where sound is scaled to conversation and where a score can be studied without suspense. The painting takes music out of the realm of drama and places it within a ritual of daily refinement.

Composition: A Theater of Two Figures and Three Curtains

The design is built from a few large, legible masses that interlock with economy. The seated woman forms a compact triangle—blue ruffled blouse, coral skirt, grey stockings—locked into the cushiony oval of the armchair. The standing musician draws a tall, pale column down the right side, softened by black piping that clarifies the garment’s fall. Between them, a brilliant vertical of red patterned textile functions like a hanging banner or a field of cutouts; it is flanked by grey-green walls whose darker floral tracery recedes like side curtains. These three verticals—left drape, red panel, right drape—frame the duet and stabilize the space.

A diagonal rhythm sweeps from upper left to lower right: the bent head of the reader, her forearm sliding across the score, the skew of the coral skirt, and the tilt of the violin neck as it descends toward the carpet. Matisse inserts a contrary diagonal in the standing figure’s bow, a slim, upright line that retards the flow and returns attention to the faces. The whole arrangement is theatrical without being staged—like stepping into a room where the music has already begun.

Pattern as Structural Music

Pattern in this painting is not surface garnish; it is the score. The red central panel, punctured with light motifs, beats out a bright, even measure that animates the middle register. On both sides, the duskier floral walls offer a slower, more legato phrase that pushes the red forward and the figures even further into prominence. The carpet’s scrolling motifs, warm and soft-edged, provide a low, continuous drone that prevents the scene from floating. Even the armchair’s upholstery participates: its neutral florals give the sitting figure an elastic frame that does not compete with her clothing.

The result is a polyphony of patterns, each with a specific tempo and timbre. The eye experiences rhythm as it moves—staccato through the central strip, andante across the walls, largo at the carpet. Sound is translated into sight.

Color Climate: Coral, Ochre, and Grey-Green in Equilibrium

Matisse divides the palette into warm and cool harmonies and then reconciles them at the figures. Warmth concentrates in the carpet and the red banner; it also flickers in the violin’s amber and in the coral skirt. Coolness arrives through the grey-green walls, the blue blouse, and the shadows that articulate hands and faces. The standing figure’s cream dress, edged in black, becomes a mediator—receiving warmth from the carpet below and cool from the wall behind. Because no region monopolizes the extremes, the room feels breathable. Light is understood as color, not glare; the forms are illuminated by their neighbors rather than by a theatrical beam.

The Seated Reader: Concentration as a Physical Curve

The woman in the chair is constructed from curved decisions. Her ruffled collar repeats in micro the scallop of the chair’s rolled arms; the curve of her back and bowed head translates attention into anatomy. Matisse simplifies hands into broad, decisive shapes that still convey their delicate work pinning the page. Her skirt is a single strong field of coral, controlled by a darker hem and the wedge of shadow between crossed legs. None of this is naturalistic fuss. It is a clear diagram of concentration: the body arcs inward, the limbs assemble around the task, and the chair becomes a cradle for thought.

The Standing Musician: A Column of Poise

The second figure is vertical but gentle. The pale dress drops in long planes broken by two key accents: the black tie at the throat and the black piping that repeats the dress’s contour. At the hem, two dotted shoes peek out—light touches that keep the column from becoming severe. Her gaze drifts downward toward the score as if measuring the tempo; one hand props lightly on the chair back, a gesture of both intimacy and rest. The other hand holds the violin by the neck with practiced ease, bow hanging like a spare line. She is not performing; she is present—an embodiment of poise.

Instrument and Score: Warm Axis and Cool Plane

Matisse uses the instrument and the sheet of music as complementary devices. The violin’s varnished body is a warm, resonant oval whose color echoes the carpet and central textile; it humanizes the cool plane of the wall. The score, by contrast, is a cool white rhombus laid across the lap, its diagonal edges energizing the seated figure’s triangle. Each object is simplified to essentials: the f-holes are a brief calligraphic flourish; the music staves are suggested, not counted. Their clarity comes from relation, not detail. You believe in them because their color and tilt make sense inside the chord of the room.

Drawing with a Living Contour

A supple, dark line flows through the painting, thickening where support is needed and thinning where air should pass. It grips the chair’s rolled arm, runs the dress’s piping, describes the violin’s waist, and trims the bowed head. Around faces and hands, line is most articulate—enough to register expression and weight but never to imprison color. This living contour acts like a conductor’s baton, cueing the entrances of bright and muted passages and uniting disparate textures within a single rhythm.

Brushwork: Candor over Finish

The surface wears its making openly. The red panel’s pattern is brushed with quick, opaque dabs that are visibly strokes; the dark walls are scumbled so undercolor breathes through; the carpet is laid from rounded, flexible touches that gather into a warm hum. In the faces, paint is thinner and more transparent, letting graphite-like underdrawing advise the features. This candor keeps the painting alive. Instead of mimicking upholstery or velvet, Matisse lets paint be paint—and in doing so, he invites the viewer to share the act of seeing rather than just the result.

Space Without Pedantry

Depth in “Musicians” arises from overlap and value steps: chair on carpet, figures before wall, banner laid against the field. The floor tilts gently upward, a Nice-period hallmark that keeps objects close to the surface. There is no receding box, no burdensome perspective. The room feels inhabitable without abandoning the truth of the canvas as a flat plane—a subtle modernism that allows sensation and structure to coexist without strain.

Rhythm and the Viewer’s Circuit

The arrangement proposes a repeatable path for the eye. Many viewers enter at the red panel (brightest vertical), descend to the bowed head, slide across the white score, drop to the coral skirt and warm carpet, then rise along the pale column of the standing figure to the violin’s amber oval and back into the red. Each lap discloses a new incident: a darker seam where sleeve meets collar, a blue-grey accent inside the seated figure’s ruffle, a tiny light on the bow’s tip, a softened edge along the wall drapery. The picture sustains attention through rhythm rather than through narrative detail.

The Psychology of Companionship

Although facial description is minimal, the relationship between the women is legible and moving. The standing musician’s hand on the chair back rests near the reader’s shoulder—supportive without intrusion. Their heads incline toward the score, two minds meeting at a page. The painting transforms music practice into a portrait of intellectual and emotional companionship. The mood is neither didactic nor sentimental; it is attentive. In this way, “Musicians” continues Matisse’s Nice-period insistence that dignity lies in ordinary acts performed with calm.

Domestic Space as Instrument

The room is not a neutral shell; it is an instrument that amplifies the duet. The red banner—central and luminous—functions like a resonant board; the darker side draperies absorb and frame; the carpet cushions and warms, allowing the figures to stand out without glare. Even the armchair’s worldly bulk matters. Its solidity counters the fragile white plane of the score, suggesting that ideas can be tender and supported at once. Space itself becomes a collaborator in the music.

Light as Distributed Reciprocity

Light is not a single spotlight but a reciprocity among surfaces. The red banner brightens the faces; the cool walls temper the cream dress; the coral carpet reflects a quiet warmth into the darker hems and chair shadows. Whites are tuned rather than absolute: the score’s white is cooler than the glints on the shoes; the standing figure’s collar is warmer than the paper. This distributed system keeps the painting from melodrama, granting the scene the evenness of daylight filtered through cloth.

Kinships and Dialogues with Sister Works

“Musicians” speaks to related canvases from 1920–1922—images of readers, violinists, and interior still lifes with striped or gridded textiles. Compared with the brighter, more open “Violinist and Young Girl,” this painting is denser: the vertical banner compresses the space; the color is deeper; the figures are brought closer to the picture plane, intensifying privacy. Compared with earlier Fauvist portraits, chroma here is moderated and drawing carries more of the load. Yet a consistent grammar links them all: large, simple shapes; a concentrated palette; a breathing contour; and the conviction that patterned domesticity can host modern feeling.

Clothing as Color Logic

Wardrobe plays a structural role. The seated figure’s blue blouse counters the warm carpet, while her coral skirt echoes it to stabilize the lower register. The standing figure’s cream dress mediates, picking up warmth at the hem and coolness at the shoulder. Black accents—necklace beads, tie, piping—serve like punctuation, clarifying syntax without overinsisting. By rejecting flamboyant costume, Matisse lets clothes become participants in the interior’s harmony rather than subjects of fashion display.

Sensation Over Description

At a glance the picture seems descriptive—two people, a violin, a chair—but its true achievement is sensory translation. You can feel the nap of the carpet without counting its fibers, the give of the upholstered arm, the satin depth of the violin’s varnish, the absorbed quiet that falls when two people study a page. These sensations are achieved by relation: warm against cool, dark beside light, curve across plane, not by inventory. Matisse trusts the eye to complete the world he proposes.

The Ethics of Calm

There is a moral dimension to Matisse’s Nice interiors that often goes unremarked. By dignifying ease and attention, they counter the frantic tempo of modern life with a poised alternative: time for learning; rooms arranged to receive thought; companionship without performance. “Musicians” does not ask us to admire virtuosity; it invites us to respect patience—the slow, shared work from which music, painting, and understanding are made.

Why the Image Endures

The painting lasts in memory because its order feels simultaneously inevitable and freshly made. The red banner, the paired figures, the surrounding dusk of patterned walls, the warm carpet underfoot—each part seems to have found its necessary place. The brush remains candid, the line alive, the color tuned to a key you can inhabit. You can look in loops without fatigue, like repeating a favorite movement of chamber music: each return clarifies structure and deepens feeling.

Conclusion

“Musicians” is a chamber piece in paint. The red central panel sets the tempo, the patterned walls hold the harmony, the carpet provides the drone, the violin and score supply melody and meter, and the two women—one reading, one standing with instrument—complete the ensemble. Matisse composes not a scene of spectacle but a room for attention, where color sustains, pattern organizes, and light distributes kindness. The result is a portrait of listening as a form of living—a modern classicism that makes calm feel like a courageous art.