Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

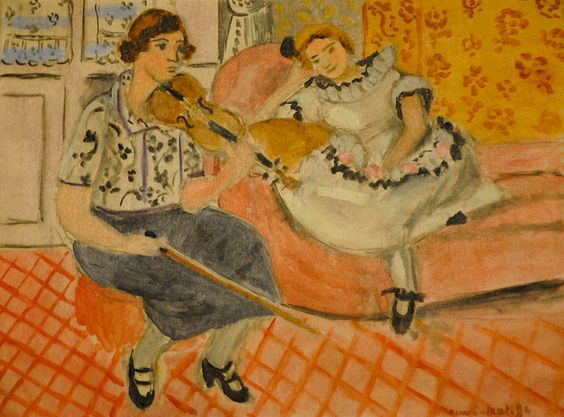

Henri Matisse’s “Violinist and Young Girl” stages a quiet domestic concert inside one of the artist’s luminous Nice interiors. A woman, dressed in a patterned blouse and dark skirt, draws her bow across a violin while a young girl in a ruffled white dress leans toward the music from a pink sofa. Around them, the room vibrates with patterned surfaces: a coral-red gridded floor, a floral orange wall, a striped or paneled window, and the pink upholstery that cradles the child. Matisse orchestrates these elements into a balanced harmony where sound seems to enter through the eye. Nothing feels stiff or ceremonial; the scene breathes with afternoon ease.

A Nice-Period Conversation Between Music and Painting

The early 1920s in Nice gave Matisse a fresh grammar for calm: measured color, spacious surfaces, and interiors tuned to human comfort. In this picture, music becomes a natural extension of that program. The violinist’s pose is relaxed, the child’s listening absorbed rather than dutiful, and the room’s patterns provide the visual rhythm that stands in for melody and meter. Matisse isn’t illustrating a lesson; he is composing a room where listening, looking, and resting coexist.

Composition as a Triad of Figure, Listener, and Room

The design turns on a triangular relationship. At left sits the violinist, her torso angled toward the child; at right reclines the young girl, her head tucked toward the instrument; and anchoring them both is the sofa’s warm oval that rises behind the child and touches the musician’s elbow. The gazes and gestures close the triangle: the violinist’s bow points toward the child, and the child’s head tips back toward the sound. A broad diagonal runs from the musician’s shoes across the floor to the child’s head, guiding the viewer’s eye through the scene in a single, legible sweep.

Pattern as Structural Music

Matisse’s patterning does the work of a rhythm section. The coral grid on the floor establishes the beat, its diagonal lattice leaning in the same direction as the bow stroke. The orange floral wall supplies a slower, ornamental phrase, its warm motifs echoing the ruffles and flowers of the child’s dress. The violinist’s blouse—sprigged with small dark shapes—adds syncopation at a smaller scale, while the window panes at left provide airy rests between passages of pattern. Together these motifs keep the eye moving without agitation, the way a steady accompaniment supports a melody.

Color Climate: Warmth, Coolness, and the Sound of Rose

The palette divides into warm and cool climates that meet in front of the sofa. The warm sector is the coral floor, pink sofa, and orange wall; the cool sector is the gray-blue skirt, pale window, and soft grays in the violinist’s blouse. The child’s white dress acts as a mediator, catching both temperatures in its ruffles and shadows. The violin’s amber wood becomes a glowing midtone that threads warmth through the cooler left half. Because no single hue bullies the others, the room feels well-ventilated—sunlight filtered through fabric rather than glare.

The Violinist’s Gesture and a Language of Ease

The violinist’s posture is essential to the painting’s mood. She sits forward on the sofa edge, elbows comfortably bent, bow hand sure but unforced. Matisse avoids the taut angles of academic figure drawing; he prefers arcs and cushions. The musician’s feet sit securely on the floor—Mary-Jane shoes and white stockings that catch small highlights—so the body’s weight is legible without heaviness. Her face, gently concentrated, is drawn with a handful of dark marks that let the blouse’s pattern and the instrument’s curves do much of the expressive work.

The Child’s Listening as a Visual Theme

The young girl embodies receptivity. Her head inclines toward the violin, hands folded or lightly clasped near her lap, one foot set on the floor as if ready to swing. The ruffled collar and skirt are painted broadly, with shadows lifted by the pink of the sofa beneath. Listening becomes visible through posture: the curve of the neck, the tilt of the torso, the way the body yields to cushion and sound. Matisse dignifies attention as surely as he dignifies performance.

The Sofa as a Shared Ground

The pink sofa supplies more than comfort; it is the physical and compositional bridge between musician and listener. Its long curve rises behind both figures and turns the rectangle of the canvas into a soft amphitheater. The sofa’s mass holds the warm center of the picture; it collects reflected light from the child’s dress and keeps the violin’s golden body from floating. With a few thick, rounded strokes, Matisse makes upholstery feel plush without fussing at details.

The Floor Grid and the Measure of Depth

The coral lattice on the floor is one of Matisse’s favorite Nice-period devices. It delivers perspective without pedantry, leading the eye toward the back wall while doubling as a steady beat. Small tilts and uneven intersections keep the grid from feeling mechanical; it remains clearly painted, not drafted. The grid’s color—red leaning toward rose—warms the bottom edge and keeps attention from falling out of the picture.

Light Distributed Rather Than Spotlit

Illumination in this room is even and humane. The window at left hints at the source, but Matisse resists theatrical highlights. Whites are tuned: the child’s dress, the window panes, and the violinist’s stockings each carry a different temperature. The violin’s varnish catches a modest sheen; the sofa’s curve glows quietly. Because light is treated as a network of relationships rather than a single ray, the figures appear gently integrated into space.

Brushwork and the Evidence of Decisions

The surface is refreshingly candid. Patterns on wall and blouse are laid in quick, clear touches; the grid is drawn with long strokes that taper naturally; the faces, hands, and instrument are summarized with decisive marks that stop as soon as the form reads. This economy keeps the painting lively. Instead of describing, Matisse proposes. The viewer completes the passage—an approach that makes the scene feel immediate rather than posed.

The Violin as a Warm Axis

The instrument itself is a visual axis. Its amber resonates with the sofa and wall, its curves echo the child’s ruffles and the arcs of the musician’s sleeves, and its diagonal neck carries the picture’s movement from left to right. The bow, a nearly straight line, contrasts with these curves and points attention toward the listener. Matisse paints the violin with respect but not fetishism; a few highlights on the belly and a darkened f-hole are enough to assert its role.

Clothing, Identity, and Modern Domesticity

Wardrobe choices signal character without theatrical costume. The violinist’s short-sleeved blouse with small dark sprigs and the dark skirt belong to the modern home, not a concert stage. The child’s white dress, with its ruff and ribbon notes, captures a slightly ceremonial playfulness. Both outfits fold easily into the room’s colors, making the figures feel at home. Matisse’s interiors depend on this harmony of person and place—dress as color, color as climate.

Space That Stays Close to the Surface

Depth in the picture comes from overlap and tonal steps rather than from strict perspective. The sofa overlaps the wall and floor, the figures overlap the sofa, and the window sits behind everything like a cool panel of light. A hint of corner on the left organizes the room, but the painting never pretends to be a box you could step into. That fidelity to the plane is a modernist promise: the painting is a made thing, honest about its surface even as it gives you space to inhabit.

The Viewer’s Circuit Through the Scene

The composition invites a reliable loop. Most viewers begin at the violinist’s face, travel down the instrument to the child’s inclined head, flow along the pink sofa, drop to the coral grid, and then climb the musician’s skirt back to the patterned blouse and window. Each lap offers new pleasures: a darker stitch of line around the child’s shoe, a small glint on the bow, a softened seam where sofa meets wall, a cool gray in the window that keeps the upper left from dissolving.

Psychological Register: Attention, Patience, and Affection

Although facial features are minimally drawn, the relationship between the pair is unmistakable. The musician’s body leans in, offering sound; the child’s leans back while turning her head, offering attention. The weft of small patterns—grid, sprigs, florals—reads as the texture of daily life: practice, patience, repetition. Matisse honors the unremarkable heroism of quiet afternoons spent learning to listen.

Dialogues with Sister Works

“Violinist and Young Girl” converses with Matisse’s other Nice-period rooms: “Morning Tea,” “Reading Woman, Daydreaming,” and “The Nice Regatta” all build their calm from patterned textiles, soft upholstery, and a clear contour. What distinguishes this canvas is the audible motif. Where many interiors set flowers on the table as visual melody, here music is literal, and yet Matisse subjects it to the same discipline: a few strong shapes, gentled color, and an arrangement that lets the scene breathe.

The Ethics of Comfort

Matisse’s interiors make a gentle argument for comfort as a worthy modern ideal. The sofa is ample; the child’s dress invites movement; the musician’s clothes allow ease; the room’s light is kind to skin and paint alike. Even the floor grid, which could read as hard geometry, feels woven because of its warm tone and hand-painted wobble. Comfort here is not indulgence. It is the condition that lets attention—musical, visual, interpersonal—flourish.

Sensation Over Description

The painting persuades less by detail than by the accuracy of relations. We feel the rough give of the floor rug, the satiny pull of the violin’s varnish, the slight scratch of the bow, the weightless rustle of ruffles, and the shared quiet that hangs in a room where people are at ease with one another. None of this is described explicitly. It is built from the right distances between notes of color, from edges that firm and release, from patterns that move at compatible tempos.

Why the Image Endures

“Violinist and Young Girl” remains memorable because it captures the kind of moment that builds a life: not a breakthrough or crisis, but a day of companionship and listening. Its harmony of warm and cool color, its balanced triangle of relationships, and its frank, edited brushwork keep it clear at a distance and rewarding up close. The eye can repeat its circuit indefinitely without fatigue, just as a melody can return without wearing out its welcome.

Conclusion

Matisse composes this interior the way a musician shapes a chamber piece. The floor grid keeps time; the patterned wall phrases a counter-melody; the sofa holds a warm drone; the violin’s amber carries the tune; and the two figures—one playing, one listening—complete the harmony. The picture achieves poise not by smoothing everything into sameness, but by letting differences cooperate: curve with line, warmth with coolness, pattern with plainness, sound with sight. What remains after looking is the sensation of a room that has learned to host attention, and of a music that lingers even after the bow has left the string.