Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

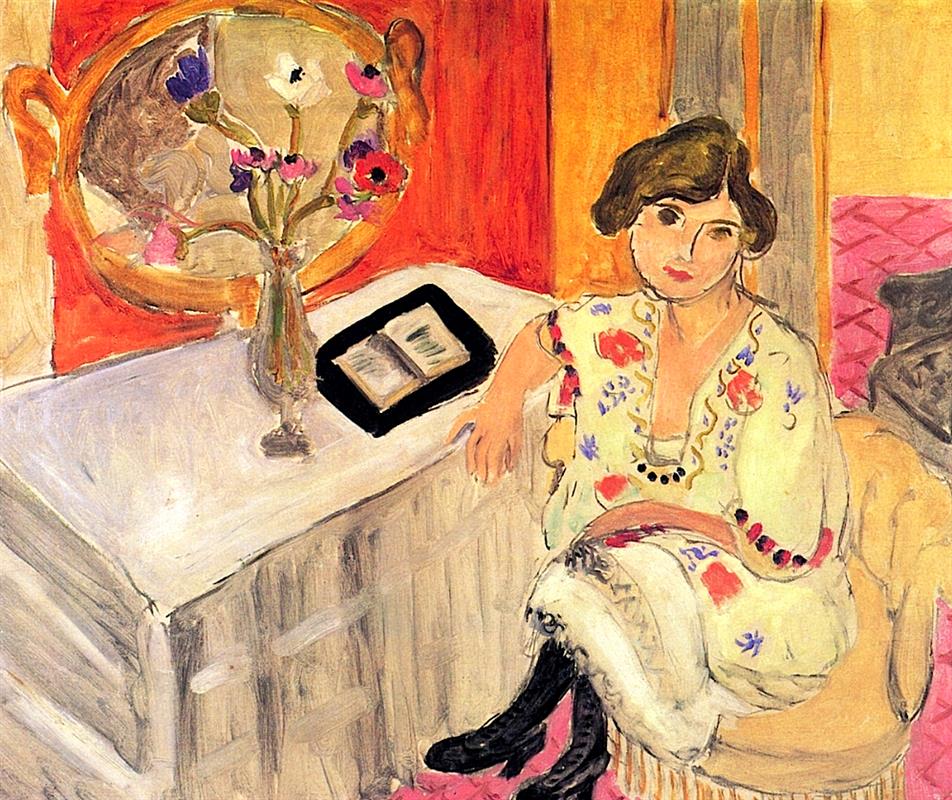

Henri Matisse’s “Reading Woman, Daydreaming” turns a modest corner of a Nice apartment into a finely tuned theatre of color, pattern, and thought. A young woman in a pale, floral dress sits sideways on a low chair, one arm draped casually over a white-covered table where an open book lies. A slim vase of anemones rises beside a round, gilded mirror that reflects fragments of room and light. Around her, swathes of orange, rose, and butter-yellow lock together with the cool whites and grays of linen and wall. Nothing heroic happens and yet everything matters: the way the hand rests, the slight tilt of the head, the reflectiveness of the mirror, the interval between stripes on the skirt and diamonds of the distant carpet. Matisse conducts these details into a harmony that feels natural once seen, as if the room had always been waiting to be arranged this way.

The Nice Period And The Poise Of Domestic Life

Painted during Matisse’s early Nice years, the canvas belongs to a moment when he pursued calm after the fractious innovations of the 1910s. Rather than abandon modernity, he reframed it. The studio becomes an instrument for balance; pattern acts as structure; windows, mirrors, and table-tops provide frames within the frame. Interiors like this do not retreat from the world—they propose a humane way to inhabit it. “Reading Woman, Daydreaming” exemplifies that ethic. It treats an ordinary interval—reading that drifts into reverie—as a worthy subject, translating psychological quiet into visual order.

Composition As A Tabletop Stage

The picture’s architecture is clear and persuasive. The table runs diagonally across the lower left, forming a platform on which the book and vase read as protagonists of a small drama. The chair and figure establish a counter-diagonal, with the sitter’s torso turning toward us while her legs angle away. Behind, vertical panels of orange and neutral gray stack like stage flats, and at the far right a wedge of rosy, gridded carpet and a dark, upholstered form provide weight. Over the table the round mirror acts as a centered disk—an anchoring sun—which gathers reflections and echoes the curve of the sitter’s head. The interplay of rectangle and circle, diagonal and vertical, produces a composition that breathes without slackness.

Pattern And Ornament As Structure

Matisse’s ornament is never mere decoration. The floral sprigs scattered across the dress—poppy reds, lilacs, and blues—are placed to articulate the body’s planes and keep the pale garment from becoming a blank block. The tablecloth’s soft, vertical corrugations give the white mass direction, guiding the eye toward the book and hand. In the right background, the diamond grid of the pink carpet reappears in a sliver only, but its angled rhythm balances the verticals elsewhere. Even the gilded mirror frame, with its ear-like handles, contributes structural curve that answers the tilt of the sitter’s arm. Pattern keeps time; it prevents stillness from stiffening.

Color Climate: Warm Fields, Cool Lifts

The palette splits into warm walls and cool furnishings moderated by the pale dress. Butter-yellow and orange planes glow behind the figure; the tablecloth, vase, and book read as cool notes; the mirror’s gold circulates warmth back into the upper left. Poppy reds pulse in the anemones and on the dress; violets and blues cool those pulses so they never shout. Black boots and necklace provide grounding bass notes, while the pale skin retains a peachy neutrality that belongs equally to warm and cool zones. The result is a climate that suggests midmorning or late afternoon light diffusing evenly through the room: intimate, breathable, and kind.

Gesture, Posture, And The Psychology Of Pause

The woman is not actively reading; she is at the edge of reverie. Her forearm flows onto the table, fingers relaxed near the book’s gutter. The other hand folds into her lap as the leg crosses beneath her dress. The head tilts slightly, eyes turned toward us but not fixed on us, as if emerging from thought rather than posing. This posture carries the painting’s psychology more eloquently than any facial detail could. It is the moment after words have been set down and the mind continues their motion privately. Matisse honors that interiority by giving her a stable seat and spacious color fields around her; attention is the room’s true furniture.

The Open Book As A Silent Engine

The open book is small, almost schematic, yet it powers the image. Its dark cover shapes a crisp rectangle against the tablecloth, a formal counter to the soft bouquet and the round mirror. The few strokes of text inside tell us that reading has occurred; the angle tells us it has paused. By placing the book between vase and hand, Matisse materializes the path from sensation to thought: flowers rising in color and scent, hand resting near pages, mind wandering. The book is less an object than a hinge between seeing and daydreaming.

The Mirror As Device And Metaphor

Matisse’s circular mirror operates on several levels. As device, it organizes the top left, catching patches of warm wall, perhaps a sliver of the artist or furniture, and consolidating them in a glowing disk. As metaphor, it stands for reflection—the mental activity implied by the title. The mirror expands the room without breaking the painting’s surface logic; it lets us feel space extending behind the table while keeping everything firmly on the plane of the canvas. The roundness also echoes the sitter’s head and the curve of the vase’s neck, tightening the network of soft forms.

Drawing And The Living Contour

A supple dark line runs through the painting, never uniform, always responsive. It firms the jaw and eyelids, loosens along the sleeve and chair rim, thickens where the wrist meets the table edge, and thins where the dress joins light. This living contour lends clarity to the broad color planes without imprisoning them. The line is a conductor, not a cage: it sets tempo, marks entrances, and keeps the ensemble coherent while letting each instrument—color, texture, reflection—play in its own timbre.

Brushwork And Material Presence

The surface is frank about how it was made. The orange wall is scumbled so the ground flickers through; the tablecloth’s whites are laid in broad, unblended passes that leave ridges of pigment; blossoms are single dabs that cohere at a distance into petals; the mirror’s interior is a churn of warm and cool strokes that never settle into literal depiction. This candor keeps the painting fresh. Instead of polishing details, Matisse edits down to relationships the eye truly registers: value against value, hue against hue, edge against breathing space.

Space And Depth Without Pedantry

Depth is constructed not with precise perspective but with overlapping planes and tuned values. The chair overlaps the table edge; the table overlaps the orange wall; the mirror floats in front of the wall yet belongs to it chromatically. The carpet wedge and dark upholstered form push the right edge forward, giving the left side permission to recede more gently. You feel the room’s volume, but you never lose the flat surface that makes the harmony legible.

Rhythm And The Viewer’s Circuit

The composition invites a looping path for the eye. Many viewers begin at the bright book on the table, travel up the vase to the bouquet, cross into the mirror’s gold disk, and then drop to the sitter’s tilted head and necklace before resting in the patterned fabric of her dress and the dark triangle of boots. The pink carpet sliver nudges the gaze back toward the tablecloth’s diagonals, and the loop repeats. Each circuit yields new small discoveries—a violet shadow tucked into a fold, a red echo from dress to flower, a faint reflection in the mirror’s interior—proof that the painting is built for long looking.

Clothing, Identity, And Modern Ease

The dress contributes more than prettiness. Its pale ground softens the composition’s heat; its floral marks carry the room’s colors in miniature; its loose fit signals modern ease rather than corseted display. The black necklace and boots punctuate the lightness with gravity. Altogether, the outfit presents a contemporary, self-possessed sitter who inhabits pattern rather than being overwhelmed by it. Matisse’s portraiture in these years repeatedly grants women this kind of poised autonomy.

Flowers As Interior Weather

Anemones—favorite flowers in Matisse’s Nice interiors—behave here like interior weather. Their dark centers rhyme with the necklace beads; their petals echo the reds and violets of the dress; their stems sketch a green counter-melody against the white tablecloth. They are quick to read and slow to exhaust: the more you look, the more their tiny value shifts and edge variations hold attention. Positioned between book and mirror, the bouquet mediates sensation and reflection, anchoring the canvas’s left half with a vertical flourish.

Kinships And Differences With Sister Works

“Reading Woman, Daydreaming” converses with Matisse’s other early-1920s interiors: “Morning Tea,” “Anemone and Mirror,” “Seated Figure, Striped Carpet,” and the many open-window scenes. In each, a few recognizably Nice elements—rounded chair, patterned textile, tabletop with flowers—are recomposed like words in a new sentence. Here the diagonal table and the emphatic round mirror give the sentence its distinctive cadence. Compared to the denser odalisque pictures of the later decade, this canvas is sparer, closer to sketch in places, and that lightness lets the psychological theme of drifting attention come through clearly.

Light As A Gentle Discipline

The canvas registers daylight not as theatrical spotlight but as a soft discipline that keeps zones in relation. The white of the book is not the same white as the tablecloth; the tablecloth’s white is not the same as the dress’s pale ground. Each is nudged warmer or cooler, brighter or duller, to fit its role in the chord. The result is a polyphony of whites that holds the picture together and prevents the orange and pinks from dominating. This careful tuning is a hallmark of Matisse’s Nice interiors and one source of their enduring calm.

The Viewer’s Place In The Room

The vantage point is slightly elevated, as if we are standing beside the table. That position is intimate but not intrusive. We can almost reach the book; we could easily speak to the sitter without forcing her to break her reverie. This hospitality is part of the painting’s ethic. It treats the viewer as a welcomed guest, not a conquering gaze. The mirror’s reflection keeps us gently aware that we, too, are inside a constructed view.

Meaning Without Program

The painting resists literary messages. Its meaning is experiential: the way reading slides into daydreaming; how pattern holds attention without noise; how a room arranged for comfort can make thought visible. The elements—the book, bouquet, mirror, clothing, and color fields—do not symbolize a hidden story; they enact a way of living. To look well at the painting is to practice the same kind of attentive ease it portrays.

Conclusion

“Reading Woman, Daydreaming” distills Matisse’s early-1920s ambition: to transform everyday intervals into durable harmonies. A diagonal table, a round mirror, an open book, a vase of anemones, a floral dress, a sliver of patterned carpet—none of these is grand alone, but together they create a room calibrated to the mind’s gentle swings between focus and drift. The brush remains candid, the contour alive, the color climate poised between warmth and cool. The picture does what its subject does: it invites us to linger, to let perception widen, and to discover that quiet is not emptiness but a carefully tuned music.