Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

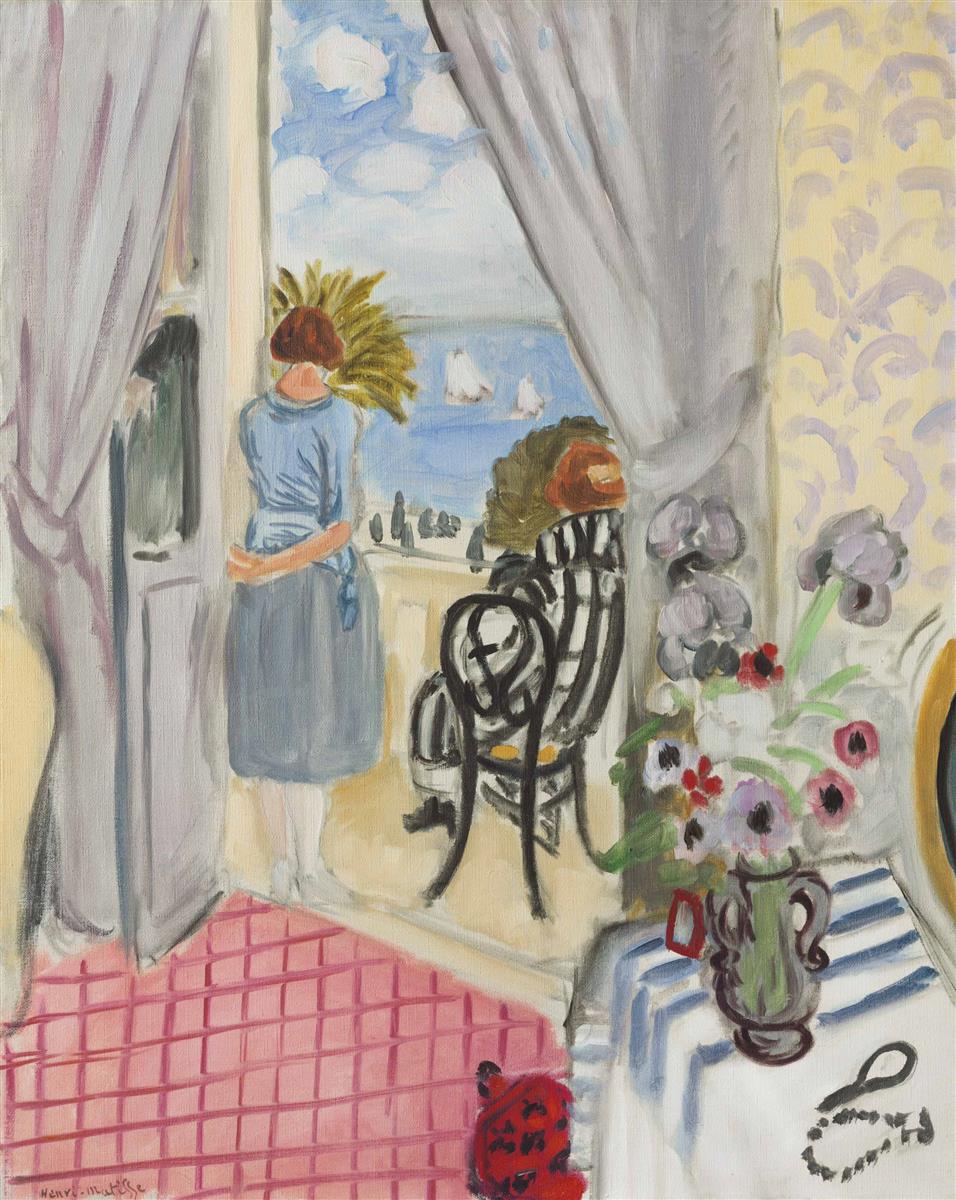

Henri Matisse’s “The Nice Regatta” stages a sun-lit interior that opens like a proscenium to the Mediterranean. Two lavender curtains part to reveal a balcony, a blue sky scattered with clouds, and small white sails gliding across the harbor. A woman in a pale blue dress stands with her back to us, hands folded, as if listening to the breeze; a black bentwood chair waits beside her. Inside, a striped tablecloth carries a green jug of anemones, while a coral-pink gridded carpet energizes the floor. Pattern, light, line, and air fold into a single harmony. The painting appears casual at first glance, but its calm depends on a precise structure: a choreography of rectangles and arcs, warms and cools, interior ritual and outdoor spectacle.

The Nice Period And A New Classicism

Painted in 1921, the canvas belongs to Matisse’s Nice period, when he pursued clarity after the shocks of the previous decade. Instead of fauve explosions, he sought what he called an art of balance—rooms organized for comfort, patterns that behave as structure, and windows that breathe. “The Nice Regatta” embodies that program. It treats leisure as a modern subject, not as decadence but as a humane arrangement of light and time. The regatta is less an event than a rhythm outside the window, a moving counterpoint to the steady hospitality of the room.

Composition As A Theater Of Openings

The picture is built around nested frames. An interior rectangle (the room) contains a secondary stage (the balcony) that in turn opens to a distant strip of sea and sky. The parted curtains act as wings, their soft V funneling the eye outward. In the foreground, the pink grid tilts toward us, pulling our bodies into the scene. At right, the striped table (diagonal) and the floral still life (oval) balance the verticals of doorway and draperies. This geometry directs a reliable viewing path: from the carpet up to the standing figure, out across the sails, back to the curving chair, and down to the bouquet and tablecloth before returning to the carpet’s pulse.

Pattern As Structural Music

Matisse’s patterns do more than decorate. The gridded carpet sets the tempo, its crisscross lines creating a measured beat that prevents the room’s paleness from drifting. The tablecloth’s blue stripes provide a second rhythm that moves the eye laterally and cools the pinks. The curtains are not fussy lace, but loose, repeated gestures that read as textile while remaining brushwork; their twin columns stabilize the window opening like slender pilasters. Even the balcony’s palm frond acts as a stylized burst that echoes the anemones’ circular blooms. Pattern, in short, is the architecture’s music, pacing our attention without ever overwhelming the human presence.

Color Climate: Warm Interior, Cool Horizon

The palette divides into complementary climates. Inside the room, warm coral, butter, and soft violets create a hospitable temperature. Outside, the harbor is all cool notes—milk-blue sky, slate band of horizon, white sails that catch the sun. The standing figure sits between these worlds in a dress that reconciles them: a blue softened by interior light. Because the interior warms and the exterior cools, the open window registers not just as space but also as a change of air. That contrast is the painting’s emotional engine: we feel the tug to step outside, yet the room remains irresistibly welcoming.

Light That Organizes, Not Theatricalizes

Matisse refuses dramatic spotlighting. Illumination in this picture acts like a rule for relationships. The sails are not dazzling white but breathable, tied to the sky by wisps of cloud; the lavender curtains pick up reflection from outside, keeping their shadows translucent; the jug’s highlights are two or three clear strokes that imply glossy clay without imitation. Light reads as a presence distributed across surfaces, not a single burst. This makes the space feel inhabitable; our eyes adjust the way they do in a real room moving toward a bright balcony.

The Figure As Witness, Not Performer

The woman in blue stands with her back to us, hands loosely interlocked at the waist. Because her face is hidden, the regatta assumes centrality without the painting turning into pure landscape. She lends scale to the balcony and cues our gaze outward, yet her modest presence holds the composition together like a hinge. Her silhouette is defined by a living contour—dark enough to steady the form, soft enough to remain part of the airy climate. The tied sash and the slight bend in her knee provide small diagonals that keep the pose from freezing. She embodies attention itself: a human measure of the day’s pace.

Furniture And Objects As Partners In Poise

The black bentwood chair is a masterstroke of economy. Its whiplash curves echo the bouquet’s arabesques and the palm’s flare, but it is empty—a reserve of rest waiting to be occupied. The green jug is scarcely modeled, yet its spiral handle and dark mouth anchor the still life like punctuation. A small red object on the floor, near the carpet’s edge, acts as a warm counterweight to the blue stripes and keeps the right foreground active. Each object plays two roles: it stands for itself and contributes to the room’s cadence.

The Open Window As Metaphor And Device

For Matisse, an open window is a way of thinking about painting. A canvas, too, is an opening—flat, bounded, yet offering depth. In “The Nice Regatta,” nested frames emphasize that dual nature. The balcony rail becomes a local horizon inside the larger horizon; the parted curtains mimic the painter’s act of revealing. This layered theatricality reminds us that we are looking at a made thing, even as the scene feels spontaneous. The device is philosophical without pomp: it says that representation and sensation can coexist gracefully.

Drawing And The Elastic Contour

The painting’s coherence depends on a supple line that thickens and thins across forms. The chair’s loops are calligraphic and assured; the figure’s outline is firmer at the elbow and softer along the dress hem; the bouquet’s stems are snapped in with a few quick darts. In the sea and sky, contour withdraws almost entirely; there, value and temperature define form. This elasticity allows interior objects to share a single graphic language while the outdoor view remains luminous and open.

Brushwork And The Evidence Of Decisions

The surface records choices rather than disguising them. Clouds are laid by single, rounded touches; the sea is swept in lateral strokes that allow the canvas to glint through like reflected light; curtain folds are quick descending strokes, each a decision about pace and width. On the carpet, the grid’s lines are pulled in confident passes that sometimes fade at the end, keeping the rhythm from becoming mechanical. This visible process matches the subject: a morning alive with small motions—breeze in drapes, boats making way, flowers shifting in water.

Space Without Pedantry

Depth is established by overlapping shapes and value steps rather than tight perspective. The pink floor tilts gently forward to meet us; the doorway jamb overlaps the balcony; the rail cuts across the figure at the waist; the sea band sits behind everything like a calm horizon. Because the cues are so clear, the eye moves out and back without strain. The painting honors modern flatness while granting enough volume to imagine stepping onto the tiles or resting in the chair.

Rhythm And Movement Across The Surface

The regatta itself supplies a quiet beat—white triangles spaced across blue. Inside, counter-rhythms answer: grid diamonds, striped tablecloth, bouquet’s roundels, chair’s loops. The alternation of vertical curtains and horizontal balcony keeps the music from becoming monotonous. The viewer’s eye moves in a loop that mirrors a seaside stroll: carpet to window, across the boats, back through the room to flowers and table, then out again.

An Ethics Of Comfort

Matisse’s Nice interiors make a moral claim for comfort. They dignify rooms arranged for human scale—seats that support, windows that ventilate, tables that host small rituals like flowers and tea. “The Nice Regatta” extends that claim to the relation between private and public worlds. Leisure on the water is mirrored by leisure at home; the threshold between them is open. The painting suggests that calm attention—to boats, to light, to a blossom on a table—is not trivial but restorative.

Dialogues With Sister Works

This canvas speaks to Matisse’s earlier window pictures and to contemporaneous interiors. From “Open Window” to Nice-period rooms, he returns to the motif to test how much he can simplify while keeping sensation vivid. Here, chroma is moderated and drawing carries more responsibility. Compared with denser odalisque rooms a few years later, “The Nice Regatta” is breezier—its patterns are shorthand, its objects fewer, its air wider. Yet the grammar remains the same: a central opening, flanking draperies, a patterned floor, a modest still life, and a figure who joins interior to exterior through poised attention.

The Figure’s Back And The Viewer’s Position

By turning the woman away from us, Matisse grants viewers an ethical space. We are invited to share her view rather than to consume her face. This arrangement lets the painting become experiential—we feel ourselves moving toward the balcony, pausing beside her, then noticing the small boats. The back-turned figure has another advantage: it leaves the regatta unchallenged as a point of interest while keeping human scale in the frame. The painting is both genre scene and landscape without contradiction.

The Bouquet As Interior Weather

The anemones are not a showy still life; they are weather inside the room. Their petals echo clouds; their dark centers mirror portholes and chair loops; their stems create green cross-rhythms with the table’s blue stripes. The jug’s olive tone joins the palm on the balcony and the cabined tree shapes beyond, stitching nature into the room. They tell us that attention here is not only directed outward; it circulates within.

Material Presence And The Beauty Of Economy

One of the painting’s quiet triumphs is how little it requires to feel complete. Figures are built from planes; objects from a few decisive highlights; patterns from repeated marks. The canvas weave remains visible, particularly in the floor and light walls, transforming emptiness into air. This economy keeps the surface fresh and the scene available. The viewer is not overexplained to; they are trusted to complete the experience.

The Viewer’s Circuit And The Pleasure Of Return

“The Nice Regatta” is made for repeated circuits: enter by the coral floor, pass through the doorway to catch the sails, trace the palm’s burst, rest briefly in the empty chair, drift to the bouquet and jug, note the coolness of the striped cloth, and return to the carpet’s warmth. Each pass yields a small discovery—the red accent near the carpet’s edge, a softened seam at the curtain tie, a pale square of sun on tile—evidence that the painting, like the day it records, rewards unhurried attention.

Conclusion

Matisse transforms a room with a view into a compact symphony of balance. Interior warmth meets coastal cool; pattern organizes without fuss; a figure witnesses rather than performs; and light behaves like air, distributed and kind. “The Nice Regatta” shows how a painter can treat leisure as a serious subject by composing hospitality—of space, of color, of time. It is a picture that doesn’t try to dazzle; it sustains. Under the open window, with the boats gliding and the flowers quietly shining, the act of looking becomes a gentle practice of restoration.