Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

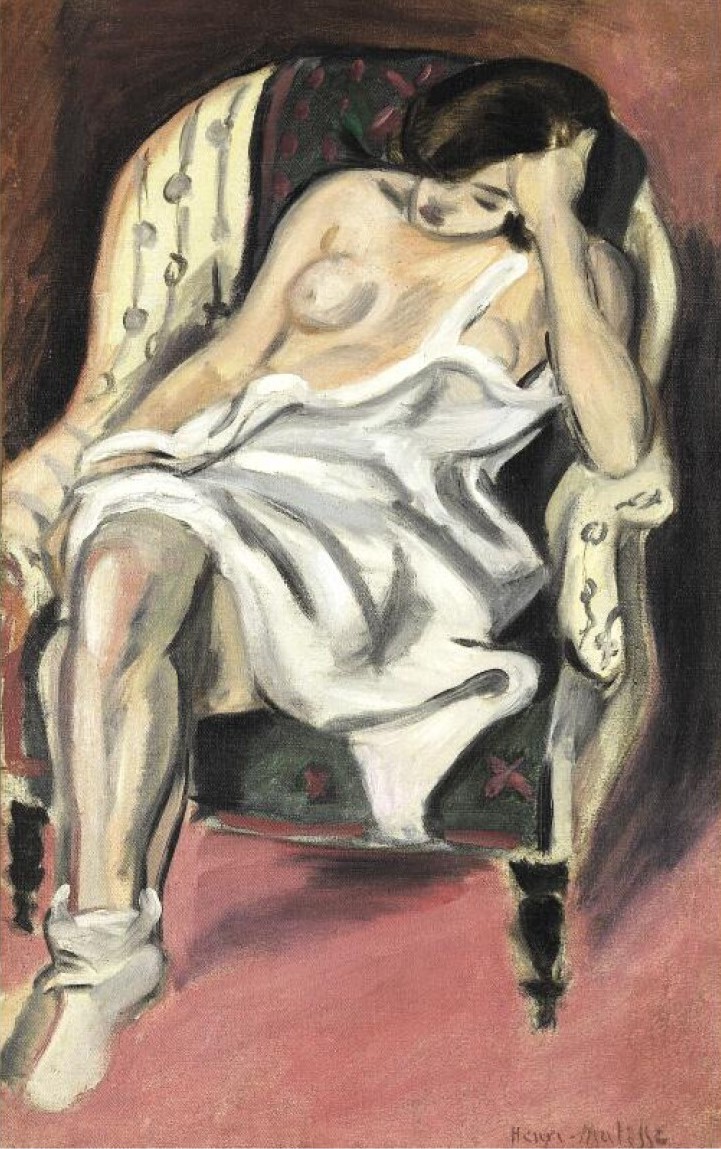

Henri Matisse’s “Nude in the Armchair” (1921) compresses a world of sensation into a modest studio corner. A young woman sits sunk into a generous chair, one forearm propped against her forehead, the other hand loosely resting near a fold of white drapery that spills across her thighs. The pose is relaxed without being lax, and the room’s color—rose carpet, softened browns, moth-green upholstery—gives the figure a climate rather than a stage. With a handful of tones and an elastic contour, Matisse achieves what many painters labor to reach with excess: a body that feels alive in air, a chair that feels built to hold it, and a mood that invites quiet attention rather than spectacle.

The Nice Period And A New Classicism

Dated 1921, the painting belongs to the opening years of Matisse’s Nice period, when he turned from the incendiary chroma of Fauvism toward a poised, modern classicism. After the disruptions of the 1910s, he chose interiors, models, patterned textiles, and coastal light as the vocabulary for a renewed art of balance. “Nude in the Armchair” exemplifies that searching calm. Bright primaries recede; measured half-tones and confident drawing take the lead. The result is not a retreat into safe prettiness but an assertion that clarity, comfort, and rhythm can be as radical as shock when handled with conviction.

Composition As Architecture

The composition is built from a few clear shapes that interlock like masonry. The chair provides the dominant oval, its arms curving outward before returning to cradle the sitter. The body sets a diagonal from the lifted forearm to the forward knee, creating a triangular mass that stabilizes the canvas. A second diagonal, made by the long sweep of white drapery, runs counter to the first and prevents the arrangement from slumping. At the base, the warm pink floor forms a horizontal plate that receives the weight of chair and figure. Nothing feels tentative. Each piece of the composition is a structural element—arch, buttress, base—so the picture stands with the serene inevitability of a well-proportioned room.

The Armchair As Cradle

Matisse treats the armchair as domestic architecture scaled to the body. Its back arcs like a shell, its arms flare with a gentle S-curve, and its upholstery, patterned in dark green with small red accents, recedes just enough to keep the figure forward. Note how the chair’s striped front legs and light outer covering catch highlights that echo the skin’s pale tones. Chair and body rhyme without merging: the upholstery’s small decorations are the quiet counterpoint to the large, simple planes of flesh. The chair is not a prop for display; it is a vessel of support, the visible partner of the body’s repose.

Palette And The Temperature Of Calm

The palette is restrained and atmospheric. Flesh is modeled in warm roses, cool grays, and creamy whites that drift toward olive at the shadows. The floor is a muted pink that does not shout, yet it radiates enough warmth to bathe the lower half of the picture. Upholstery and background settle into deep greens and tempered browns; these cool notes keep the scene from overheating and give the flesh a gentle stage to glow against. White drapery provides the brightest value, but Matisse tempers it with gray-violet inflections so it belongs to the same climate. This tuning produces a sensation akin to early evening light in a quiet room—soft, breathable, and steady.

Light That Builds Rather Than Dazzles

There are no theatrical spotlights here. Light is constructed out of relationships: cool against warm, pale against mid-tone, matte against glossier strokes. A narrow highlight along the shin, a glint on the forearm, and a ridge of light across the drapery’s edge are enough to convince the eye of volume. Shadows are shallow and transparent; they contain color rather than obliterating it. By refusing deep chiaroscuro, Matisse lets the picture remain luminous from corner to corner. Light is not an effect added after the fact; it is the element that organizes the whole.

The Living Line

Matisse’s dark contour is the picture’s quiet engine. It thickens at joints and edges that must bear weight—the knee, the elbow, the rim of the chair—and thins where flesh should breathe into air—the shoulder’s turn, the outer thigh, the drapery’s soft fall. The line never cages the body; it conducts it. In the arm that supports the head, a firm arc both describes bone and transmits the sensation of pressure. Along the chairback, quick, repeated touches tie upholstery to frame. This elasticity of contour allows large regions of color to remain open and fresh while staying coherent in the wider design.

Brushwork And The Evidence Of Decisions

The surface records the painter’s choices without apology. Long, loaded sweeps shape the drapery; shorter, responsive strokes knit the upholstery; scumbled passages let the ground flicker through in the background, creating vibration without noise. Flesh is built from broad planes that drift into one another rather than from finicky modeling. Where he wants emphasis—the crease where torso meets thigh, the shadow under the breast—Matisse strengthens edges with a darker stroke and then lets them soften a few inches away. The viewer senses an artist editing in real time, pruning every passage down to what is necessary and sufficient.

The White Drape As Pictorial Pivot

The white cloth draped over the model’s lap is the painting’s visual pivot. It introduces the highest key in the palette and a dominant diagonal that cuts across the chair’s great curve. Its folds catch light in crisp bands that play against the soft sheen of skin. As a motif it does triple duty: it provides modesty without prudery, it cools the composition’s warm lower half, and it gives Matisse the occasion to stage a ballet of edges—hard against the knee, frayed along the hem, swallowed by shadow where the cloth tucks beneath the thigh. Few elements in the picture accomplish as much with such economy.

Anatomy Treated As Light And Weight

Rather than cataloging muscles, Matisse renders the body as an interplay of light, weight, and temperature. The lifted arm creates a shaded plane that cools the face; the forward shin gleams because it tilts toward the window; the torso sinks slightly into the chair, registering mass without heaviness. The breast is drawn with a few decisive curves and a single, anchored shadow—clear, dignified, and free of fuss. The figure is unidealized: knees are knobby, knuckles visible, skin varied. This honesty makes the sensuality more convincing. We believe the body because it has not been polished beyond recognition.

Pattern And Plainness In Counterpoint

The chair’s interior fabric carries dark motifs—a handful of spots and small stars—that beat gently beneath the figure. Around them, the outer covering of the chair is kept nearly plain, marked only by a few rhythmic dots that suggest upholstery tacks or embroidery. The floor and background are more or less flat fields. Against this quiet, the drapery’s folds and the model’s contour perform like melody over drone. Pattern here is not decoration added for its own sake; it is the ground rhythm that allows the eye to measure the intervals between major forms.

Space, Depth, And The Modern Surface

The scene is undeniably shallow—the wall presses close; the carpet rises like a tilted plane; the chair is cropped by the edges—yet nothing feels cramped. Matisse engineers depth through overlapping and value rather than receding lines. The seat slips behind the leg; the leg rests on the floor; the arm crosses the torso; the head nestles into the arm. These overlaps create a chain of spatial facts strong enough to convince, even as the painting maintains the flat coherence prized by modernists. You move into the space just far enough to feel present, then you are returned to the surface to enjoy its orchestration.

Gesture, Psychology, And The Ethics Of Looking

The model’s head rests against her hand in a gesture that reads as thought or simple rest. Because the face is turned downward, the painting avoids the thrust of direct voyeurism. The body is offered for sustained looking, yet the person remains inward. Matisse’s nudes from Nice often strike this balance: they acknowledge sensuality without staging it as conquest. The ethics of the image is built into its structure—supportive chair, protective drapery, climate of soft light—so the viewer’s attention becomes a form of companionship rather than possession.

Comparisons Within Matisse’s Practice

Seen beside “Nude in an Armchair” of 1920 or “Nude in a Chair” from the same year, this work tightens the composition and deepens the warmth of the palette. The earlier pictures often place the figure within wider windows and lacy curtains; here the world contracts to chair, body, and floor, intensifying the exchange among them. The 1921 canvas also points forward to the odalisques of the later decade, where patterned textiles and languorous poses proliferate. What remains constant is the grammar: enclosing curve, counter-diagonal, tempered color, and a line that breathes.

The Rose Ground As Emotional Key

The floor’s muted rose is not a mere background. It sets the painting’s emotional key—domestic, humane, quietly warm. By saturating the lower third with this note, Matisse ensures that the colder greens and browns above do not chill the figure. At the same time the rose is moderated by gray; it glows rather than burns. The color reads as carpet and as air, as place and as mood, a double function that anchors the whole.

Rhythm And The Viewer’s Circuit

The picture guides the gaze along a dependable path. One typically begins at the bright ridge of the drapery, rides its diagonal to the forward knee, glides down the shin to the foot resting on the pink ground, and then sweeps back along the chair’s arc to the bowed head. From there the eye crosses the shadowed forearm, returns to the breast, and descends once more to the pale cloth. This loop can repeat indefinitely, and each pass yields new minor rewards: a softened seam where chair meets wall, a dark accent at the upholstery’s edge, a whisper of gray modeling along the ribs. The painting is designed for this kind of slow circulation.

Material Presence And The Beauty Of Economy

Much of the work’s authority lies in how little paint is needed to say so much. Edges are not fussed; transitions are stated in two or three tones; large passages remain open and breathable. You can sense the tooth of canvas under thin scumbles, especially in the background, and you can see the confident slip of the brush at the drapery’s turns. The material facts—oil, bristle, weave—are never concealed; they are enlisted to articulate flesh, fabric, and air with maximum efficiency. The economy is not meagerness; it is precision.

Modern Comfort As Subject

“Nude in the Armchair” elevates a modern virtue—comfort—into worthy subject. The room may be sparse, but everything in it serves the body: the chair that receives it, the cloth that cools it, the light that flatters without glare. This notion of luxury—measured by rightness rather than opulence—runs through Matisse’s Nice interiors. In the wake of anxiety and upheaval, such images of considered ease carry ethical resonance. They argue that calm is not complacency; it is care made visible.

The Lessons Of Restraint

The painting demonstrates how restraint can heighten sensuous experience. By limiting color, simplifying forms, and keeping the surface candid, Matisse ensures that every small variation counts. The faint violet drift in a shadow becomes meaningful; the shift from cool to warm along a calf reads as body heat; the firmness of a contour at the elbow registers as weight. Restraint doesn’t suppress feeling here; it amplifies it.

Legacy And Continuing Relevance

Works like “Nude in the Armchair” illuminate why Matisse remains central to discussions of modern painting. They show how a picture can honor the flatness of the canvas while granting viewers the pleasures of volume and atmosphere; how decoration can act as structure; how the ordinary can carry lasting grace when orchestrated with intelligence. The canvas also anticipates the late cut-outs in its reliance on large, legible shapes and the primacy of silhouette, even as it retains the sensuality of brush on linen.

Conclusion

“Nude in the Armchair” achieves an equilibrium that feels inevitable once seen. Chair, body, drapery, ground, and air cooperate in a chord of soft warmth and tempered cool. The line breathes; the color reassures; the brush speaks plainly. Nothing is overexplained, yet everything is clear. What could have been a stock studio pose becomes, in Matisse’s hands, a complete environment for attention—a place where looking slows to the pace of breath, where comfort has dignity, and where modern painting shows its power to make serenity vivid.