Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

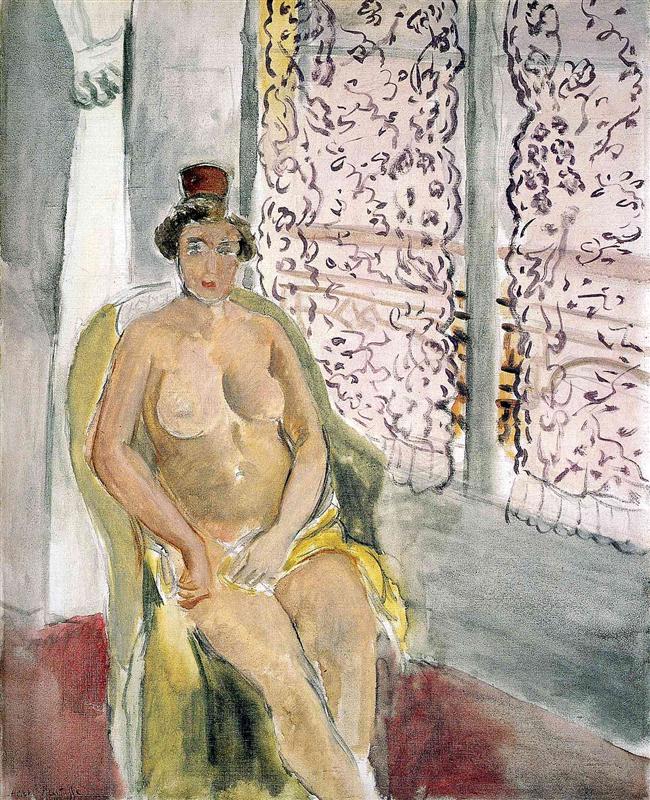

Henri Matisse’s “Nude in a Chair” (1920) is a study in quiet audacity. A seated model occupies a low, yellow armchair; a small red cap perches on her hair; two tall windows dressed with lacy, mauve curtains filter an even light into the room. The floor is a cool gray that fades toward the walls, while a warm crimson carpet flares in the foreground like a low ember. Nothing is extravagantly described. Instead, spare lines, translucent passages, and a precisely tuned palette conspire to create a mood of humane candor. Matisse asks how little is needed to make a body feel present, a room feel breathable, and an image feel inevitably complete. The answer, here, is very little—if every decision is exact.

Matisse in 1920 and the Turn Toward Poise

The year 1920 marks the beginning of Matisse’s Nice period in earnest, when the turbulence of the prior decade yielded to a search for equilibrium. He favored interiors, studio light, patterned textiles, and models at ease. Yet the work is not a retreat into decoration; it is a rigorous inquiry into balance. “Nude in a Chair” belongs to the moment when he discovered that the calm of a room could be radical if it clarified relationships among line, color, and shape. The canvas does not court the shock value of early Fauvism; it tests how serenity itself can carry vitality, how restraint can make touch more vivid, and how an honest, unidealized figure can feel both private and public in the best sense.

Composition as an Architecture of Frames and Voids

The design is built from nested rectangles and soft ovals. The window bays form tall, pale panels that rise like translucent columns; the curtains hang in vertical streams of lilac marks; the chair creates a rounded pocket that cradles the model; and the red carpet stakes a firm slab at the bottom edge. The figure is set slightly left of center, her legs angled to the right, so the room’s symmetry remains alive rather than rigid. The open void of floor between chair and windows is as important as any object—it allows the air to move and gives the nude a field of repose. The composition presents a conversation between enclosure and openness: the chair protects, the windows release, and the body mediates.

The Chair as Domestic Architecture

Matisse treats the armchair as a kind of architecture scaled to the body. Its yellow covering is brushed in broad, economical sweeps, darkening to olive at the shadows and cooling toward the edges where light skims. He outlines its curved rim with a confident, dark line that thickens and thins, granting the form a weight that remains elastic. The chair is not furniture-as-luxury; it is a device of support. Its enveloping shape echoes the model’s shoulders and knees, so that body and seat read as interlocking parts of a single structure. The message is subtle: comfort is not an afterthought but a principle, a modern value as worthy of painting as any historic grandeur.

Pose, Gesture, and the Ethics of Presence

The model sits upright, one hand resting close to her lap, the other easing the drape at her thigh. The small red cap, a witty accent, punctuates a face rendered with sparing marks—eyes, brows, and mouth indicated without fuss. There is no coyness and no theatrical languor; the body bears its own weight, the gaze meets the world. Matisse’s nude is neither a classical ideal nor a provocation. She is a person at rest in a room, held by light and furniture and her own composure. The crossed ankle, the slight cant of the hips, and the squared shoulders establish a triangular stability that keeps the figure dignified even as paint remains loosely handled.

Light, Air, and a Tempered Palette

Color here is climate. The cool whites of the windows merge into pearl grays that modulate across the floor and up the wall; the lace curtains carry a mauve that repeats in the sitter’s lips and softens the room’s chill; the chair’s yellow imparts warmth that diffuses into the nearby skin. Nothing is saturated to the point of clamor; every hue is tempered by air. This restraint is crucial to the painting’s candor: the skin reads as luminous because it is calibrated against these quiet surrounds. Highlights are few and placed carefully—on the cap, along the shoulder, at the knee—enough to suggest moisture and life without sliding into polish.

Brushwork and the Evidence of Making

The surface preserves the act of painting with frankness. Thin washes lie beside thicker, buttery notes; scumbles let the ground flicker through; a drawn contour sometimes wanders and is caught by a second, more decisive pass. The curtains are a cascade of quick, calligraphic strokes that read as lace without being counted; the carpet is a reddish field where the brush’s pressure creates darker whorls and lighter flats; the gray floor shows long, watery pulls that evaporate at the edges. This variety in facture is not casual. It keeps the image breathing, and it clarifies which parts must carry weight (the chair rim, the knees, the breast) and which can remain airy (the wall, the curtain, the far floor).

Drawing, Contour, and the Living Line

Matisse’s line is a conductor—never a cage. Around the torso it thickens to convey mass, then thins along the forearm so that skin can dissolve into light. At the jaw it is firm but not harsh, preventing the face from melting into the background; at the knee it curves decisively, anchoring the leg in space. The line also orchestrates the room: it traces the window mullions just enough to keep the architecture legible and threads through the chair’s edge to maintain rhythm. This living contour allows planes of color to remain open and unlabored, while still participating in a drawing that holds the whole together.

Drapery, Modesty, and the Rhythm of Yellow

A small yellow drape slides from the chair to the model’s lap, echoing the upholstery’s hue in a lighter key. Its role is compositional first and narrative second. It softens the transition between chair and skin, introduces a diagonal that counters the vertical windows, and provides a lighter yellow that keeps the palette buoyant. At the same time it introduces a whisper of modesty, signaling the sitter’s agency within a genre historically prone to objectification. The fabric is painted in a few broad, transparent strokes, allowing the structure beneath to remain visible and honest.

Patterned Curtains and the Language of Ornament

The lace curtains are a wonder of abbreviation. Matisse lays down a steady column of mauve, ribboning it with arabesques that suggest floral repeats without leaving the realm of paint. Their purpose is structural as much as decorative: the vertical pattern holds the tall window planes together, vibrates against the cool light to prevent dead whiteness, and mirrors the arabesque energy that will define his odalisque interiors later in the decade. Pattern, in his hands, is a way of pacing the eye, of setting a soft beat that harmonizes with the body’s curves and the chair’s roundness.

Space, Depth, and the Poise Between Flatness and Volume

“Nude in a Chair” sustains a delicate balance. The room is shallow, its planes flattened by broad, even light; yet the figure sits in convincing volume. Matisse achieves this by using value and temperature rather than illusionistic modeling. The floor cools and darkens as it recedes; the wall brightens near the windows; the body warms where blood is close to the surface and cools along the shaded flanks. Perspective lines are minimal, but overlaps are clear: the chair in front of the windows, the drape over the chair, the body within the chair. The result is a space that feels tangible without violating the modern surface.

Relation to Tradition and to Matisse’s Own Path

This painting is in conversation with a long history of the seated nude—from Renaissance Venuses to Ingres’s odalisques—and with Matisse’s own earlier breakthroughs. Unlike academic nudes, which often polish flesh into porcelain and embellish settings into fantasy, he opts for ordinary light and a real chair. Unlike his high-chroma Fauvist bodies, he restrains color to let drawing and air do more work. The small cap nods playfully to exoticism without letting costume drive the image. The overall effect is a modern humanism: the nude as a person in a room, not a myth in a tableau.

The Psychology of the Room

The room’s psychology is as finely calibrated as the palette. The windows promise outwardness; the chair affirms shelter; the carpet’s warm patch suggests a locus of habitation and repeated use. The model is neither absorbed in the viewer nor lost in reverie; she is simply present. That neutrality is part of the painting’s ethical stance. Instead of performing emotion, it creates a climate in which attention can settle. The viewer is asked to look with the same fairness Matisse applies to his subject: without embellishment, without haste, without anxiety.

Rhythm and the Viewer’s Path Through the Image

The painting invites a repeated circuit. The eye typically enters at the cap’s red, slides down the facial planes to the shoulder, drifts across the chest to the diagonal of the drape, then moves along the knees and shin toward the red carpet. From there, it climbs back through the chair’s yellow arc and out to the pale windows where the lace beats time. Each pass reveals small, considered incidents—the cool edge along the left arm, a greenish underglaze in the chair, the faint seam in the window mullion. The painting rewards patience not with hidden symbolism, but with a steadily intensifying sense of coherence.

Material Presence and the Beauty of Economy

Economy is the work’s abiding virtue. Few colors; fewer lines than one expects; a surface that refuses polish yet never feels unfinished. The model’s body is mapped by broad planes with only the most necessary transitions. The chair’s structure is secured by a handful of contours and temperature shifts. The windows accomplish their task with negative space, soft gray shadows, and the lace’s mauve script. Even the carpet is more suggestion than depiction, a red field whose darker curls deliver movement without competing. This economy is not austerity; it is generosity, because it leaves room for the viewer’s own eyesight and memory to participate.

Anticipations of the Odalisque Decade

Within a year or two, Matisse would paint odalisques draped in patterned shawls, reclining on divans before screens and mirrors. “Nude in a Chair” anticipates that flowering while remaining simpler. The arabesque curtains prefigure ornamental screens; the warm carpet previews patterned textiles; the chair’s embrace foreshadows the divan’s curve; the cap glances toward the studio’s costume trunk. Yet the picture retains the freshness of a stripped experiment, a template in which the essentials—figure, seat, window, light—have been solved with uncommon clarity.

Meaning Without Program

It is tempting to ascribe narratives to nudes: availability, seduction, exoticism. Matisse refuses these scripts. The model’s upright pose, the daylight, the ordinary chair, and the painterly candor dismantle the theatrical apparatus. What remains is a scene about attention, equilibrium, and the everyday conditions that make looking feel humane—soft light, supportive furniture, breathable color, and a pace of marks that matches the room’s calm. The meaning of the picture is that these conditions, arranged with care, can be deeply moving.

Conclusion

“Nude in a Chair” distills Matisse’s early 1920s ambition: to compose serenity without dullness, to honor the body without spectacle, and to let line and color speak in measured, persuasive tones. The chair’s yellow, the curtains’ mauve, the floor’s cool grays, and the figure’s warm planes cooperate in a chord that feels inevitable after you’ve seen it. The canvas does not dazzle; it steadies. It keeps faith with the ordinary and, by doing so, makes the ordinary luminous. In a century often defined by rupture, Matisse offers a different achievement—the construction of rooms where attention can rest, where bodies can be present without performance, and where painting itself can breathe.