Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

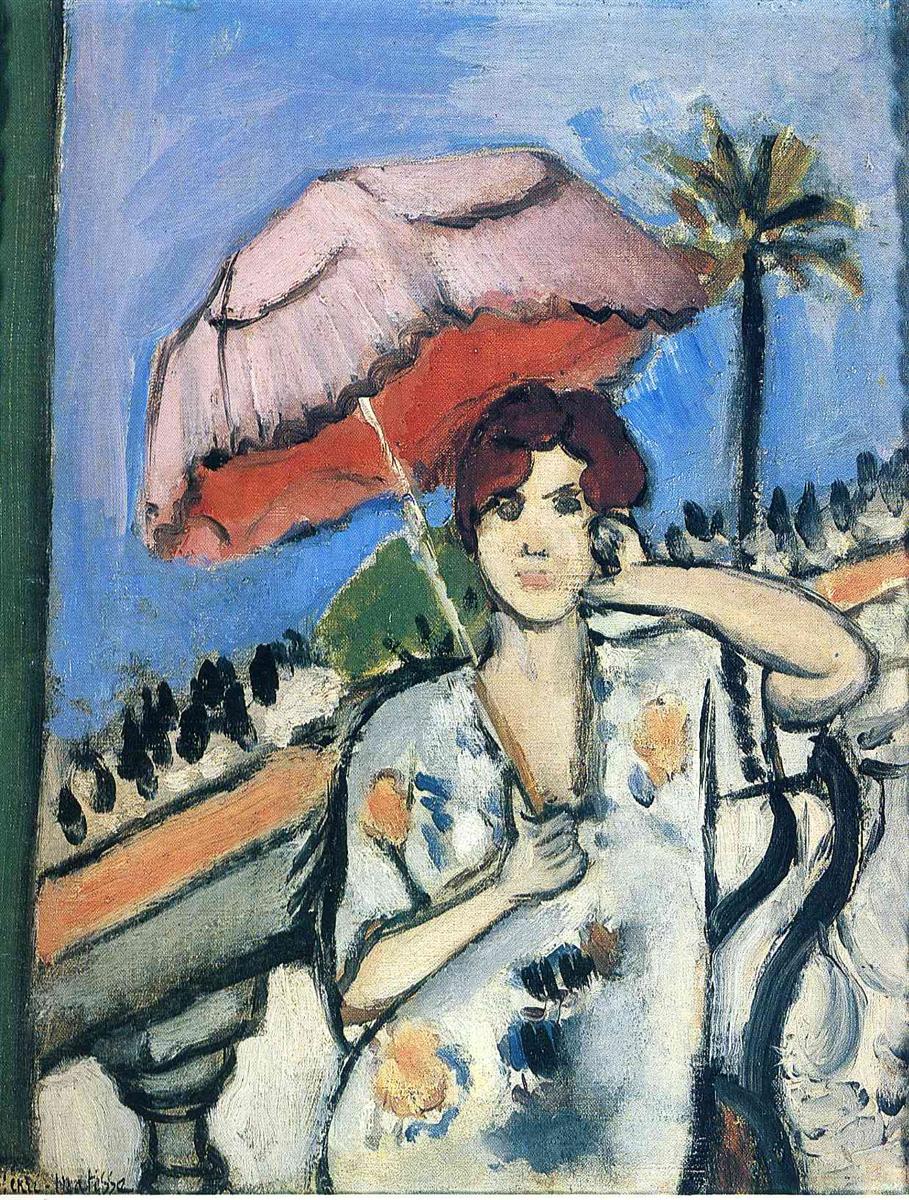

Henri Matisse’s “Woman with Umbrella” (1920) captures a luminous slice of Mediterranean life and distills it into a language of clear contours, buoyant color, and effortless rhythm. A seated woman holds a parasol that blooms above her like a second sun, casting a warm coral shadow while the sky glows in cool, expansive blue. Behind her, a palm tree and balustrade sketch the setting with a few decisive strokes. Her robe, patterned with loose floral marks, slides across the arm of the chair in airy folds. The image is simple, but the pleasures are layered: Matisse turns everyday leisure—shade, breeze, view—into a refined conversation between line and color, between decorative pattern and human presence.

Historical Context: Matisse in Nice After the War

The painting belongs to Matisse’s early Nice period, when he sought calm and clarity after the turbulence of World War I. In these years he worked with softened palettes and measured compositions, often inside sunlit rooms that opened to terraces and sea. Rather than the blazing shocks of his Fauvist decade, he pursued a modern classicism in which balance mattered more than bravura. “Woman with Umbrella” fits this program. It offers serenity without stiffness and brightness without glare, the steady poise he prized in the 1920s.

Composition as a Theater of Curves and Diagonals

The composition is anchored by a dialogue of arcs and slants. The umbrella crowns the upper half with a wide, scalloped ellipse; its handle drops diagonally to the sitter’s hand, which is set just left of center. The woman’s body curves in an answering S-shape, elbow raised to her cheek, shoulder flowing into the chair’s serpentine arm. Across the middle ground, the balustrade cuts a counter-diagonal, guiding the eye toward the palm and the stretch of sky. A narrow vertical band at the far left reads as a pilaster or shutter, stabilizing the scene with architectural weight. The geometry is spare but precise: the parasol’s dome holds the composition like a canopy, the diagonals create flow, and the verticals keep the whole from drifting.

Color and Tonal Climate

Matisse organizes the painting through a tempered but radiant palette. The sky is a saturated, slightly violet blue laid with open strokes that let the ground breathe through, creating the feel of moving air. The umbrella holds two temperatures: a cool, dusty pink on top and a warm, coral underside that glows against the face and hair. The robe is mostly white, but it is never chalky; pearly grays and faint blue-greens turn its planes, while blossoms of apricot, ocher, and muted cobalt quicken the surface. The palm contributes olive and sap greens, and the balustrade is a structure of grays and warm stone tones. Black lines bind these zones together, functioning as a color in their own right. The total effect is coastal light simplified: cool expanse above, warm shelter near the figure, and a robe that mediates the two.

The Parasol as Architecture and Emblem

The umbrella is more than a prop; it is the painting’s structural crown and its emotional key. As architecture, it spreads a protective arc that centers the composition and supplies a luminous ceiling to the scene. As emblem, it signals modern leisure—shade chosen rather than sought, time suspended rather than hurried. Matisse paints it with economical planes, allowing the scalloped edge to oscillate between pink and red-orange. The minimal modeling and crisp contour make the umbrella both solid and weightless, a device of shelter that simultaneously opens the picture to the sky’s brightness.

The Figure’s Gesture and Modern Poise

The woman’s posture is relaxed and alert, a combination Matisse admired. With one hand she holds the parasol’s staff, with the other she props her cheek, as if listening to the day. The raised elbow introduces a strong angle that interrupts the robe’s long vertical, preventing passivity. Her face is simplified—eyes and brows stated with quick darks, mouth a warm note—yet the expression is specific: present, inward, unhurried. She sits comfortably within pattern and color, emblematic of Matisse’s modern figure who inhabits decoration rather than being buried by it.

Line as a Living Conductor

Matisse’s dark contour is flexible and decisive. It tightens around the brim of the umbrella, slackens along the robe’s edges, thickens where the chair’s arm turns, and thins where flesh meets fabric. These variations do not merely describe; they set tempo. The line is a conductor’s baton, cueing quick phrases in the blossoms and longer phrases in the sky and balustrade. By letting the line remain visible, he aligns the figure with the rest of the scene; everything is drawn into the same graphic key.

Brushwork and the Evidence of Making

The surface of the painting retains the pleasure of its construction. In the sky, long, lightly broken strokes allow undercolor to glint through, suggesting breeze without literal clouds. The palm is a burst of quick, radial marks attached to a single shaft—botanically spare, optically convincing. The robe’s floral patches are compact dabs and ovals, their edges feathered so they settle into the fabric’s light rather than sit on top of it. The balustrade is a series of abbreviated cylinders and bands, painted with enough density to carry weight but not so much as to deaden the rhythm. This candid facture keeps the picture fresh; you sense choices made in real time, not labor smoothed away.

Space and the Breath of the Outdoors

Depth is established with minimal means. The balcony rail pushes horizontally, the palm rises just behind it, and beyond both lies the wide blue sky. There is no fussy atmospheric perspective; distance is a matter of scale, overlap, and value. Because the sky occupies such a large field, it becomes a reservoir of visual oxygen, preventing the patterned robe and warm parasol from closing the space. The viewer feels both proximity to the sitter and the openness of the day—the intimate and the expansive held together.

Light, Shade, and the Temperature of Air

Light here is diffuse coastal sun modulated by the parasol. Matisse avoids theatrical highlights; instead he uses small temperature shifts to create shade. The coral underside of the umbrella cools slightly near the edge; the face receives that reflected warmth, deepening the hair and softening the cheek. On the robe, shadows are made from bluish grays that turn gently, suggesting a luminous fabric rather than a stiff white. The result is an image where light behaves like air—present everywhere, never overwhelming.

Pattern and Fabric as Structure, Not Ornament Alone

The robe’s floral marks are not merely decorative sprinkles. They provide beats within the white field that keep the garment from flattening into a block. Their placement follows the body’s topography: blossoms enlarge around the torso, shrink toward the sleeve, and thin at the hem, so the pattern helps us read form even as it remains delightfully abstract. This is Matisse’s long-standing strategy—use ornament to carry structural information and to set emotional tone at once.

Rhythm and Movement Across the Surface

The painting moves in gentle pulses. The umbrella’s scallops create a repeating rhythm along the top; the balustrade’s slanted band and the row of dark foliage create a second, smaller rhythm across the middle; the robe’s blossoms add a third, softer beat below. These linked rhythms keep the eye circulating. The result is kinetic without agitation, like the sway of parasols and palms in mild wind.

A Conversation with Fauvism and with the Nice Interiors

“Woman with Umbrella” carries forward the lessons of Fauvism—flat color units, strong contour, pleasure in saturation—but in a moderated key. The pinks and blues are tuned rather than explosive; the drawing is more structural, the modeling more present. Compared with the interiors Matisse painted around the same time—women in armchairs, patterned carpets—this canvas takes the same grammar outdoors. The parasol functions as the indoor canopy, the sky as the calm wall, the balustrade as the stabilizing edge of a table—continuities that reveal how consistent his compositional thinking was across genres.

Leisure as a Modern Subject

The subject is leisure, but it is not idle display. In the early 1920s, to picture ease and comfort carried a quiet ethical charge—a counterimage to years of hardship. Matisse paints leisure as attention: the posture of looking, the apparatus of shade, the simple luxury of time with light and air. The woman is not performing; she is present. The painting suggests that delight in color and form can itself be a humane value.

The Viewer’s Path Through the Image

The painting guides the eye along a dependable circuit. One typically enters via the broad pink of the umbrella, follows the staff down to the hand, lingers at the face, then traces the robe’s blossoms across the lap to the balustrade. From there the gaze moves up to the palm and out to the sky before returning to the umbrella’s edge and beginning again. Each loop yields small surprises—a darker seam inside the parasol, a quick drag of gray across stone, a sly blue note amid white fabric—that keep looking active.

Material Presence and the Beauty of Economy

Economy is one of the work’s quiet triumphs. The palm is a dozen strokes; the balcony, a handful of bands and ovals; the umbrella, three or four tonal zones; the face, a few well-placed planes. Yet nothing feels thin. Because each stroke is well judged, the parts accumulate into a fullness that belies the spareness of means. This restraint lets the painting breathe and keeps it hospitable for long viewing.

Psychological Tone and the Ethics of Looking

The sitter’s expression is calm and open. Her raised elbow and resting cheek suggest thought, not pose. Matisse grants the viewer proximity while preserving the subject’s autonomy. The parasol is instrumental here: it frames rather than exposes, sheltering the figure inside her own climate. The painting thus models a way of looking that is attentive without being consuming—a distinction central to Matisse’s portraits and interiors of the decade.

Conclusion

“Woman with Umbrella” condenses a day’s ease into a lucid arrangement of arcs, bands, and tones. The umbrella’s rosy canopy, the robe’s pale field, the palm’s crisp flare, and the wide blue all cooperate in a balanced chord that feels inevitable once seen. Nothing is overstated; nothing is undernourished. Matisse orchestrates the scene so that the viewer experiences both intimacy with the figure and the freshness of the outdoors. In this balance lies the painting’s charm and its permanence. It is not just an attractive seaside vignette; it is a compact lesson in how line can breathe, how color can set climate, and how leisure can be shaped into art with clarity and kindness.