Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

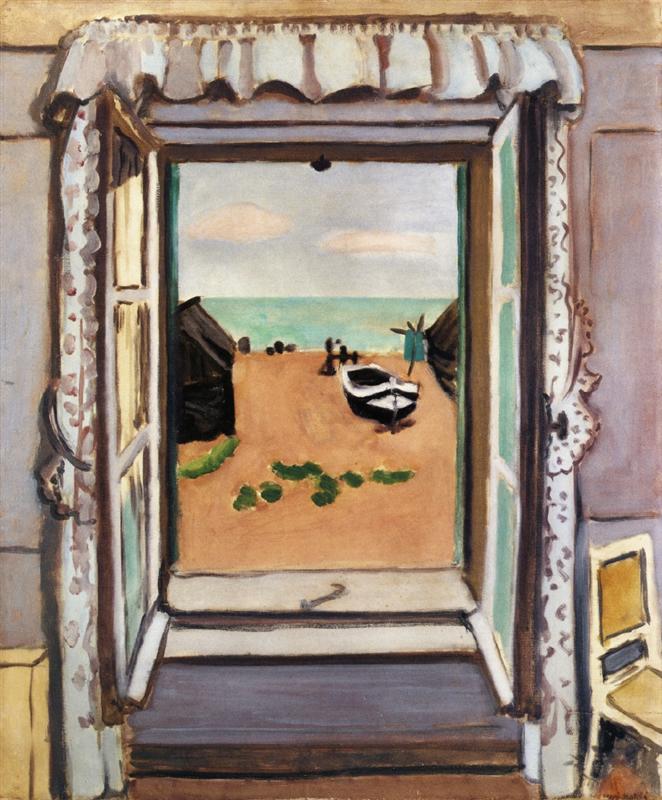

Henri Matisse’s “Open Window, Étretat” (1920) is a painting about a threshold. From a quiet room, we look through parted curtains and open casements toward a strip of Normandy beach, a turquoise band of sea, and a few beached boats. The composition is disarmingly simple—interior framing device, exterior view—but the experience of the picture is rich and layered. Matisse organizes the scene so that line, color, and space converse across the sash. The result is not just a view of the coast but a meditation on passage: from room to shore, from private to public, from measured interior light to the bright clarity of day.

Matisse in 1920 and the Return to Calm

Painted at the start of the 1920s, this work belongs to Matisse’s postwar pursuit of clarity, poise, and balance. After the high-voltage color of Fauvism and the disruptions of World War I, he sought a modern classicism grounded in economy of means. Interiors became crucial laboratories for that search. They provided architecture, pattern, and a controllable light with which he could test relations among line and color. “Open Window, Étretat” carries this project outdoors without leaving the stable ground of the room. The landscape is present, but always shaped by the intelligence of the interior frame.

The Open Window Motif in Matisse’s Oeuvre

The open window recurs throughout Matisse’s career as a structure for thinking: it is a ready-made proscenium that turns looking into an event. In earlier canvases the window often opens onto a saturated Mediterranean port; here it reveals a cooler northern shore. What remains constant is the idea that painting can hold two spaces at once and stage the very act of perception. The window is not only a subject—it is a model of the canvas itself: a bounded surface that proposes depth and air while remaining, stubbornly, a flat rectangle.

Composition as a Theater of Frames

The picture is built from nested rectangles. The wall and jambs define the largest; the open sash, with hinges and latches brushed in brisk strokes, creates a second; the outdoor view becomes a third, smaller stage pushed back in space. A scalloped valance softens the top edge like a theatrical curtain, while patterned drapes hang to either side, their floral marks abbreviated but lively. The floorboards and thresholds lead the eye forward with measured steps, then halt it at the sill where the exterior rectangle takes over. It is a deliberate, almost architectural handoff: the room ushers you to the edge, the view pulls you across.

Space and the Choreography of Depth

Depth is not thrust at the viewer; it is carefully paced. We begin in the foreground with the cool-violet floorboards, feel the first threshold, then the second, and only then enter the light of the beach. The recession is confirmed by scale cues: the white boat, mid-beach, occupies only a small portion of the view; beyond it, huts and figures shrink to signs; at the far end, sea and sky meet in a clean line. The horizon sits high enough to expand the beach’s breadth, making the outside feel spacious without overwhelming the interior. Matisse thus converts the passage from near to far into a felt duration—our eyes walk to the water.

Color: Warm Earth, Cool Sea, and Moderated Whites

The palette is restrained and tuned. The interior is built from quiet violets, grays, and pale creams that register as shade and painted wood. The seaside is warmer in the sand and cooler in the sea: ocher and terra-cotta on the beach, a lucid turquoise-green in the water that brightens toward the horizon. Whites are never raw. The boat’s white is tempered with gray; the curtains’ white carries mauve and beige; the sky’s clouds are peach-tinted, reflecting the warmth of the sand. This moderation lets the color breathe. The viewer senses fresh air outside and a gentle, tempered light within.

The Function of Black and the Discipline of Line

Matisse’s flexible dark line—sometimes brown, sometimes near black—gives the image its clarity. It sharpens sash edges, articulates the inner corners of the window, and crisply outlines the beached boat so it reads at a glance. But the line also knows when to recede: along the distant huts, it softens into loose silhouettes; along the curtains, it thins, letting pattern and ground merge. Black is never merely outline; it is a color that adjusts from cool to warm and from firm to soft depending on the neighboring hue. That responsiveness keeps the structure precise without freezing the painting into diagram.

Brushwork and the Evidence of Making

The paint surface remains candid. In the floorboards, long pulls of the brush leave bristle striations that echo the boards’ grain. The curtains are laid with quick, fluid marks that suggest both fabric and air. Outside, the sand is brushed in broad, flat strokes that allow the canvas tone to glow through, while the sea is a thin, even band, the brush moving laterally to register calm water. The boats and huts receive denser accents, placed decisively rather than elaborated. This economy respects how we actually register scenes: we read the architecture and the strong shapes first; the mind fills in the rest.

The View as a Working Shore

Matisse’s Étretat is not a cliffside spectacle but a working beach. The white boat, a modest craft, sits ready on the sand. Dark huts flank the passage toward water, the right-hand one hung with a bright rectangle of laundry that introduces a humane note. Small figures punctuate the mid-distance like commas, implying conversation and labor. By choosing this unglamorous corner of the coast, the painter aligns the exterior with the interior: both are places where daily life unfolds at human scale. The grand subject here is not maritime drama but the ordinary fact of a day that invites stepping outside.

Curtains, Valance, and the Poetry of Privacy

The patterned drapes and scalloped valance are not mere decoration. They announce that the viewer stands in a private, cared-for space. Their scallops and floral marks are feminine without fussiness, domestic without heaviness. They soften the geometry of the window and establish a rhythm that the seaside view echoes in the repeated silhouettes of boats and huts. And they propose a tender idea: that beauty enters life not only through vistas but through the things that frame them—the fabrics we choose, the way a room modulates light, the threshold we cross to meet the day.

Thresholds as Structure and Metaphor

Few motifs in modern painting have been as productive for Matisse as the threshold. Here, three distinct steps lead to the sill. Each is painted as a sober plane of cool violet or gray, with a thin dark crease at the joint. Structurally, these bands deepen the foreground and counter the sunlit expanse beyond. Metaphorically, they slow the viewer, turning the outside view into an invitation rather than a command. We feel the pause of the threshold in our bodies—a measured inhalation before we would walk into the brightness.

The Psychology of Stillness

Although the beach contains figures, the painting feels exceptionally quiet. The interior is empty of people yet full of presence; the outdoor activity is reduced to gentle signs. This stillness has a psychological dimension. The open window suggests welcome, but the absence of a person in the room leaves the viewer alone with the decision to step out or stay. The scene becomes a picture of choice and of ease: a room that releases rather than confines, a beach that is available rather than demanding. In a postwar moment, that gentle freedom carries palpable relief.

Comparisons with Earlier Open Windows

If the famous 1905 open window from Collioure beams with Fauvist heat—geranium reds, electric greens—this 1920 version exemplifies Matisse’s mature restraint. The earlier picture revels in shock; the later builds resonance through balance. Yet the two are kin. Both hinge on a central rectangle of exterior light and both convert the frame of a window into a compositional engine. The difference is a matter of temperament. In 1920, Matisse trusts a narrower palette and devotes more attention to pacing, to how the eye travels and returns. The result is a sustained chord rather than a bright fanfare.

Human Presence Without Figure

A yellow chair sits cropped at the lower right, its back turned to the window. That ordinary object stands in for the person who would occupy the room. It also doubles as a structural counterweight, its warm note echoing the sand and anchoring the interior. This is one of Matisse’s gentle tricks: the suggestion of life through things. We sense coffee cups not shown, pages not depicted, a body that has risen from the chair to look outside. The painting respects that intimacy by refusing to dramatize it.

Light as Architecture

Matisse uses light to build the picture. The brightest unit is the beach rectangle: a sheet of honeyed tone broken by small darks and a white hull. The next brightest are the inner faces of the window frames where outside light brushes the wood. The dimmest are the floorboards and the interior wall, kept cool and even. This hierarchy organizes attention—not by bossy contrasts, but by gently stepping values. The eye is led where the structure wishes it to go, then allowed to browse among secondary delights: the green laundry note, the tiny peach clouds, the soft wear along the sill.

The Modernity of Simplification

The painting’s modern character does not hinge on novelty of subject but on the way Matisse simplifies to essentials. He keeps drawing explicit, color tempered, edges negotiated rather than hard. He lets décor serve structure and lets structure serve the experience of looking. Abbreviation is not laziness; it is fidelity to perception. At the distance implied, a hut is a wedge, a figure a dot, a boat a bean-like silhouette with a white rim. By painting these facts clearly, he leaves room for memory and association to do their work.

The Viewer’s Path Through the Image

The picture choreographs a loop. We begin at the bottom in the cool, quiet room; cross the thresholds; enter the sunny beach; glance left and right at huts and figures; skim the sea’s horizon; then return via the strong verticals of the casements and the scalloped valance. On the next pass we notice smaller incidents: the hinge plate, the faint shadow of a latch, the leaflike patches of beach grass, the diagonal hoofprint or tether mark in the sand. The image rewards unhurried attention without ever demanding that we decode a narrative.

An Image of Hospitality

“Open Window, Étretat” has the temperament of hospitality. It offers the outdoors without insistence, the indoors without enclosure. The window stands open not as a dramatic gesture but as a daily habit—this is how the room breathes. The painting’s friendliness lies in its willingness to share the simplest pleasures: a path of light, a hint of salt air, a chair waiting to be turned toward the view. In making these pleasures the subject of modern art, Matisse also makes a claim about value: that clarity, comfort, and measured beauty deserve a central place in how we picture the world.

Conclusion

This canvas condenses many of Matisse’s lifelong concerns into a single, lucid arrangement. The open window furnishes a frame within the frame; thresholds pace the viewer; colors modulate the temperature between room and beach; line holds the parts together without stiffness; and a working shore supplies human scale. Nothing here is spectacular, and that is the point. The painting finds depth in ordinary passage—stepping from shade into light—and returns that experience to us with calm precision. We leave the image feeling that the day is kind, the sea breathable, and the room ours to occupy or to leave at will.