Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

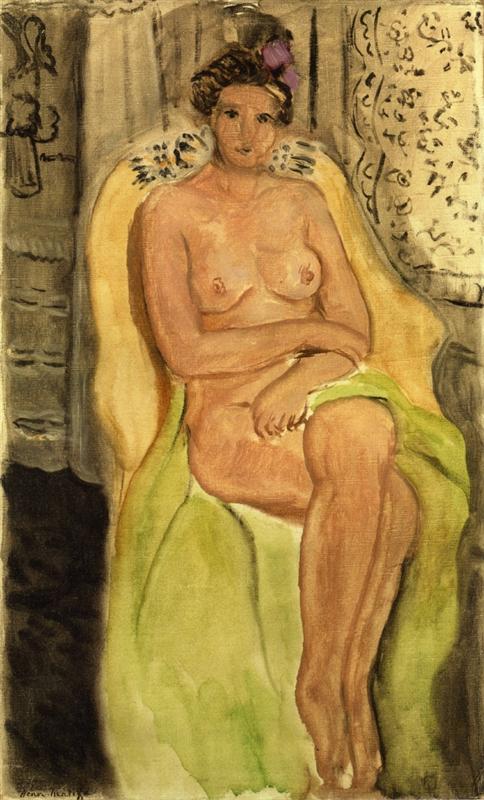

Henri Matisse’s “Nude in an Armchair, Legs Crossed” (1920) distills the intimacy of a private room into a poised, luminous image of repose. A nude model sits deep in a yellow armchair, her legs crossed, a green drape slipping over her thighs, and her gaze directed forward with quiet steadiness. Around her, a pale interior takes shape in spare planes—shadowed wall at left, patterned curtain at right, a suggestion of furniture beyond the chair’s curved back. Nothing about the scene strives for theatrical effect; instead, the painting offers a hushed equilibrium where contour, color, and atmosphere hold each other in balance. It is characteristic of Matisse’s postwar interiors: restrained in palette, rich in sensation, and designed to be read through rhythm rather than detail.

A Postwar Turning Point

The year 1920 marks an important turn in Matisse’s practice. After the explosive chroma of Fauvism and the disruptions of World War I, he sought a classical clarity that did not sacrifice sensuality. Settled for long stretches on the Mediterranean coast, he returned again and again to interiors flooded with gentle light, to models at rest, and to the decorative language of fabrics and furnishings. “Nude in an Armchair, Legs Crossed” belongs to the opening chapter of this Nice period. It tests how serenity can be achieved with simplified means: a limited range of colors, a few essential lines, and the carefully paced breathing of the brush. The result is not a retreat from modernity, but a refined assertion that painting can be both decorative and rigorous.

The Pose and Its Meanings

The figure’s crossed legs shape the entire composition. One thigh angles diagonally forward; the opposite knee rides high, creating a triangular mass that stabilizes the lower half of the picture. The torso remains frontal, but the head inclines slightly, imparting a note of inwardness. Hands are placed naturally—one laid across the lap, the other resting along the chair’s arm—so that the body’s weight registers without theatrical strain. The pose communicates comfort rather than display, dignity rather than provocation. It also concentrates attention on the meeting point of limb and drape, where Matisse choreographs transitions from warm flesh to the cool green cloth with consummate economy.

Composition as an Architecture of Curves

The painting is designed around concentric arcs. The chair’s scalloped back cradles the model like a shell. The contour of the crossed legs repeats the chair’s curve in a tighter register, while the drape drops in a soft, vertical fold that cuts through the curves and prevents the structure from collapsing into a circle. At the edges, the upright bands of wall and patterned curtain act as buttresses. This nested construction—a large curve holding smaller curves, interrupted by a measured straight—creates the sense of a room that supports and protects. The figure is not isolated on a pedestal; she is embedded in an architecture of comfort.

Color and the Temperature of Calm

Matisse calibrates color to produce a specific kind of calm. The chair’s yellow is mellow rather than blazing; it leans toward straw and butter, allowing the nude’s warm rose-browns to read clearly against it. The green drape is a fresh, slightly acidic note that cools the lower half of the canvas and balances the warmth above. Background tones—grays, beiges, faint lavenders—are kept deliberately neutral, so they frame without competing. These choices build a tonal climate like late morning light in a shuttered room: cool along the periphery, warm at the center, and unified by breathing air. Color here is not spectacle but atmosphere, an emotional weather that cues the viewer toward repose.

The Living Line

Matisse’s black or brown contour, elastic and controlled, is the painting’s subtle engine. He outlines the shoulder with a stroke that thickens at the joint and thins along the arm, letting the line carry the sensation of weight and softness together. Around the knees and ankles, he permits the contour to loosen, allowing the flesh to breathe into the surrounding light. In the chair he uses the line structurally, reinforcing the crest of the backrest and the curve of the arms so that the furniture feels built rather than merely described. This living line is never a prison; it is a conductor’s baton, setting tempo and phrasing for the blocks of color.

Flesh Painted as Light

Rather than mapping anatomy with hard modeling, Matisse treats the body as a field through which light passes. The sternum is suggested by a shift in temperature, the belly by a wide, transparent wash that deepens toward the hip, the clavicles by soft accents rather than sculpted edges. Transitions are achieved by floating one color into another, not by meticulous hatching. The effect is at once sculptural and dematerialized: the viewer understands mass and volume, yet nothing feels heavy. This approach avoids the academic habit of cataloging muscles and instead locates sensuality in the felt vibration of tone.

The Green Drape as Pictorial Pivot

The drape is the hinge of the composition. Its cool green breaks the continuum of warm flesh and yellow upholstery, creating a visual pause. Its fold follows the line of the crossed leg, emphasizing the triangle that anchors the pose. It also serves a narrative function: a reminder of modesty, of clothes just set aside, of the encounter between softness of skin and softness of fabric. Matisse’s handling here is particularly deft—broad, translucent passes at the top, heavier paint at the hem—so the cloth reads as both weight and air. Through this single prop, he achieves color balance, compositional clarity, and psychological nuance.

Pattern, Privacy, and the Room

At the right edge a chinoiserie-like pattern flutters across a pale curtain or screen. The marks are abbreviated, almost calligraphic, yet they signal the cultivated privacy of the room. On the left, darker verticals evoke a door or paneling sunk into shadow, a counterweight to the bright pattern. These background elements do not distract; they create the sensation of an interior with depth and history. Matisse allows them to remain soft and slightly porous, which keeps the figure forward without isolating her from the space that shelters her.

Light, Air, and the Pace of the Brush

Even where shadows are present, they feel airy. Matisse achieves this by keeping the paint flexible—thin glazes laid next to more opaque notes, visible bristle tracks that carry the direction of light, broken edges that let the ground’s warmth show through. The skin’s sheen is a painterly illusion made from matte pigment; the light is not theatrical radiance but an even humidity that reveals form without carving it. This breathable handling sets the tempo of the canvas: a slow, steady pulse rather than a dramatic crescendo.

The Gaze and the Ethics of Looking

The model meets the viewer directly, but her expression is composed, almost meditative. There is none of the coyness or performative languor that can inflect studio nudes. Crossing her legs and resting her forearm upon them, she sets her own boundary. Matisse, for his part, stages the body with respect for ease: the chair supports, the drape softens, and the room’s quiet acknowledges the sitter’s personhood. The painting participates in the long tradition of the nude while adjusting its terms—less spectacle, more presence; less possession, more companionship in a shared space of calm.

Dialogues with Tradition and Modernity

The picture carries echoes of Ingres’ classicism in its clear outline and frontal repose, yet Matisse refuses the porcelain finish and hard idealization associated with academic nude painting. Instead he pairs the linear clarity with a modern economy of paint and a decorative intelligence drawn from textiles and interiors. Compared with Renoir’s dissolving warmth, Matisse is cooler and more architectural; compared with the earlier Fauvist blaze, he is tempered and deliberate. The painting thus finds its modernity not in disruption, but in the serene reconfiguration of inherited forms.

Relationship to the Odalisque Series

Within a year or two of this canvas, Matisse would embark on the odalisque series, multiplying variations on the seated or reclining model surrounded by patterned screens, carpets, and cushions. “Nude in an Armchair, Legs Crossed” contains the DNA of those later works in a concentrated form. The armchair becomes, in the odalisques, a divan; the green drape becomes a patterned textile; the plain wall becomes a lattice of screens. What remains constant is the organizational grammar: strong enclosing curve, central figure of calm, intervals of pattern and plane, and color used to tune emotional temperature. Studying this painting is like listening to the quiet overture of a symphony soon to bloom.

Material Presence and the Beauty of Economy

Part of the work’s authority comes from its material honesty. There is no attempt to hide the weave of the canvas where washes thin out, no compulsion to polish every transition. Small hesitations and corrections—the soft edge along the shin, a slight darkening under the left breast, the strengthened line at the chair’s crest—reveal the painting as a sequence of decisions. This visible thinking gives the canvas a human temperature and allows the viewer to reconstruct the act of making: the broad lay-in of chair and wall, the measured development of the figure, the late addition of sharper accents to reinforce the structure.

The Viewer’s Path Through the Image

The painting guides the eye along a deliberate circuit. From the highlight on the shoulder, the gaze follows the diagonal of the forearm to the crossing of the knees, then rides the green contour of the drape down and back up into the shadowed hollow of the chair. From there it lifts along the inner curve of the backrest to the sitter’s face, where the cycle pauses before beginning again. Each loop is steadied by background verticals and quickened by small accents—the purple ornament in the hair, the darker nip of the navel, the glint of light along the chair’s arm. This choreography converts stillness into tempo and makes the act of looking a kind of breathing.

Serenity Without Stasis

Achieving serenity without stasis is the painting’s subtle triumph. The crossed legs create a compact, stable base; at the same time, the inward tilt of the head, the gentle torsion of the torso, and the flowing edge of the drape supply life and asymmetry. Likewise, the room is quiet but not inert: pattern trembles at the right, an ambiguous shadow opens at the left, and the chair’s yellow seems to hold warmth like upholstered sunlight. Matisse’s economy lets these mild tensions register and then subside, so that the viewer leaves with a feeling of restfulness rather than of arrest.

A Human Scale of Luxury

The painting proposes a humane definition of luxury. Nothing here is ostentatious: the chair is comfortable, the textile plain, the room modest. Luxury resides in time and attention—in the way a body can settle into a seat, in the way color settles into equilibrium, in the way a painter can give measured care to every passage. After the scarcity and turmoil of the preceding years, such domestic fullness carries quiet ethical weight. The image honors the basic conditions of well-being: warmth, privacy, gentleness of light, the ability to rest and to be seen as one chooses.

Conclusion

“Nude in an Armchair, Legs Crossed” exemplifies Matisse’s postwar poise. With a limited palette and a restrained vocabulary of lines, he composes a room where body, furniture, and air conspire to produce calm. The crossed legs anchor the design; the green drape adjusts the temperature; the living contour conducts the eye; the background offers a soft architecture of privacy. Nothing feels overworked, yet every inch is considered. In this synthesis of comfort and clarity lies the painting’s enduring appeal: it teaches the viewer how to look slowly and to recognize beauty not as display, but as balance sustained in time.