Image source: wikiart.org

A Room Framed by a National Holiday

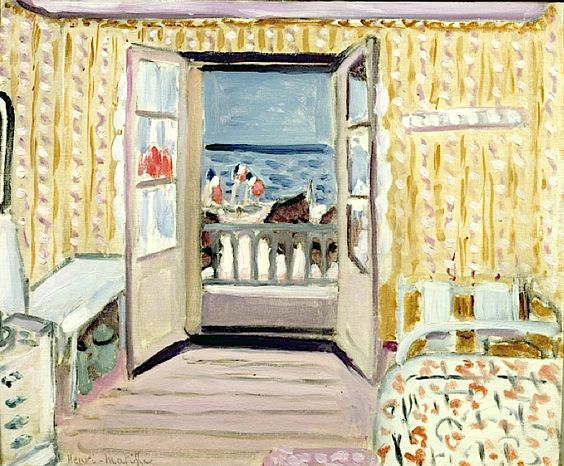

Henri Matisse’s “Interior, July 14th, Étretat” (1920) is a poised meditation on how a domestic space can hold a public celebration. The canvas shows a small seaside room whose open French doors reveal a balcony and, beyond it, the Channel under a high sky. In the middle distance small, bright touches of red, white, and blue read as flags and bunting, signaling Bastille Day. The date matters: instead of painting the parade, Matisse paints the pause—an interior that opens just enough to admit civic color while remaining a sanctuary of pattern, light, and ordinary things. The work exemplifies his postwar classicism: calm structure, lucid color, and a belief that modern life can be composed from simple, necessary relations.

Étretat in 1920 and Matisse’s Two Coasts

Matisse in 1920 moved between two coasts: the brilliant Mediterranean around Nice, where he painted luminous interiors, and the Channel around Étretat, where cliffs and weather made a moodier register. This picture blends both climates. The wallpaper’s warm pattern and the pale floorboards recall Nice; the cool sea band and heavy horizon belong to Normandy. Instead of choosing one optic, he lets them meet in a single room where interior heat and marine air cooperate. The Bastille Day motif places the painting in lived time, yet Matisse refuses anecdote. He stages structure, not spectacle.

Composition as a Theater of Thresholds

The open doors at the center are the canvas’s hinge. They split the wallpapered wall into two equal fields and create a narrow procession of spaces—room, threshold, balcony, sea, sky. The doors themselves are slightly canted, their inner edges darker where shadow gathers, their glass panes brushed thin so they hold reflections without turning opaque. A balustrade bar, painted in quick verticals, interrupts the exterior once more before the eye reaches water. This stacking of planes makes depth legible with almost no perspective tricks. The viewer’s path is simple: enter at the foreground, stand in the doorway, and let the horizon steady the breath.

Pattern as Architecture, Not Decoration

The interior surfaces carry a repeating vegetal motif in a yellow-cream key. These marks are not filler. They stabilize the large wall areas and set the room’s tempo, a soft syncopation that the eye unconsciously counts while traveling toward the opening. The bedspread’s scatter of warmer notes riffs on the wall’s rhythm at a different scale, while the tabletop’s cloth is left quieter, allowing the white rectangle to serve as a visual pause. Matisse uses pattern as a structural device: it prevents monotony across big planes and makes the open rectangle of the doorway feel both intentional and generous.

The Palette’s Warm–Cool Treaty

Color is a truce between warm domestic tones and cool maritime bands. Inside, creams, pale violets, and biscuit yellows form a hospitable atmosphere. Outside, a deepened blue sea under a paler sky cools the composition without chilling it. The small red-white-blue accents near the balcony read as holiday flags and, more importantly, as chromatic pivots that connect interior and exterior. Those patriotic notes repeat the painting’s core chord—warm whites and cool blues—while the small reds enliven both sides of the threshold. The palette is festive but never loud; its cheer is measured.

Light as Even Weather Rather Than Spotlight

The illumination feels like late morning under a thin cloud—bright enough to clarify edges, soft enough to avoid hard cast shadows. The floorboards are brushed in pale lavender that suggests light pooling and receding without theatrical glare. Door jambs glow along their inner planes; wallpaper warms where it turns toward the balcony. Matisse evokes light through small value steps and temperature shifts instead of high-contrast modeling. The result is an image that keeps the eye alert without fatiguing it.

Furniture as Companions of Daily Life

At left a narrow dressing table or console runs toward the door, its top catching a cool tint from the outside air. At right, a brass or painted-iron bed enters the frame with a patterned cover that echoes the wall. These pieces do not announce wealth or style; they register use. Their colors are tuned to the room’s chord so they participate in structure rather than compete with it. Matisse treats furniture as companions: unassertive presences that hold the human scale and offer touchable surfaces for light to land on.

The Balcony as Painting Within the Painting

The view through the door is deliberately compressed into a small seascape. A mid-height horizon divides sea and sky; small dabs near the balustrade indicate people and flags; deeper tones suggest boats or rocks. This insert works like a second canvas nested inside the first, a cool chord inside a warm one. Matisse keeps it spare so it reads instantly as air and public space. Because it is spare, the wallpapered room can keep talking; interior and exterior take turns rather than quarrel.

Bastille Day as Color, Rhythm, and Human Presence

Bastille Day’s presence is subtle. There is no marching band, no fireworks. Instead we read the holiday through chromatic signs: red-capped strokes among whites and blues on the balcony and quayside. These marks serve three functions. They verify the title’s date; they introduce human scale and movement without clutter; and they give the composition a quick, syncopated rhythm that answers the wallpaper’s beat. The celebration becomes part of the painting’s grammar, not a subject staged in front of it.

Brushwork That Lets Materials Behave

The room is painted with a vocabulary of touches matched to each surface. Wallpaper motifs are dabbed and pulled, leaving a slight grain that feels like cloth or matte paint. The floor is swept in broader, horizontal strokes that keep it planar. The doors’ edges are stated with firmer lines that anchor the central opening. On the balcony, tiny, loaded dabs suggest flags and heads—the brisk handwriting of a painter who knows when one stroke is enough. Nothing is enameled; the surface retains the life of decisions.

Space Honest to the Picture Plane

Though the painting describes recession toward the balcony, it never sacrifices the truth of the canvas. The central opening is a rectangle on a flat wall; the floor’s perspective is gentle; the wallpaper pattern does not deform under exaggerated angles. These choices keep the viewer mindful of looking at an ordered arrangement of color while still granting the pleasure of a believable room. It is the balance Matisse perfected around 1920: not illusionism, not abstraction, but a classicism that respects the surface.

The Psychological Climate of Hospitality

No figure sits in the room, yet a social mood pervades it. The bed is made; the table is clear; the doors are open as if to welcome a breeze and a friend. The holiday colors outside register as a community at play, but the room remains a place for one or two people to pause, dress, and step out. The painting suggests a way of inhabiting a celebration—near enough to hear it, distant enough to keep one’s own rhythm. It is a portrait of a day when exterior joy and interior poise cooperate.

Dialogue with Earlier Window Pictures

Open doors and windows have a long tradition—from Vermeer to Monet to Matisse himself. What distinguishes this image is the equality it grants to the patterned room. The doorway does not steal the show; it shares it. Where a Romantic might dramatize the view and cast the interior as shadowed frame, Matisse sets a balanced duet. The wallpaper keeps time; the sea sings melody; the doorway conducts.

Relations within the Étretat Series

Alongside this canvas Matisse painted Étretat’s cliffs, boats hauled on the beach, and women seated in the sand. In those works, mass and weather dominate. Here the coast arrives domesticated, a band of blue domestically framed. The series thereby covers both sides of coastal life: public shore and private room. Read together, they show Matisse’s larger concern—how a few well-placed relationships can present a whole day’s world.

Edges That Tell the Story

Edges in the painting are expressive. The dark line at the bottom of the threshold stops the viewer from tumbling outside; the light along the inner stiles of the doors performs as a beacon; the soft fade of wallpaper toward the corners prevents the room from becoming a box. Even the thin lavender band along the ceiling is an edge that speaks—an atmospheric cap that keeps the wall from climbing out of the picture.

Sound, Time, and Seasonal Weather

The canvas is quiet, but it implies a soundscape: flags clacking lightly, voices rising from the promenade, the hush of surf under a long sky. The time feels early afternoon, post-ceremony, when the parade has dispersed into seaside strolls. Seasonal cues point to summer: doors wide to the air, thin light drapery, pale floor, and a floral bedspread. Matisse captures the languor that follows public excitement, when the day stretches and the room keeps its own slower beat.

Lessons in Color and Spatial Design

The painting teaches useful principles. Use a patterned field to stabilize large color areas without heaviness. Set a cool, banded exterior inside a warm interior to generate depth without deep perspective. Place the opening dead center when you want calm inevitability; angle doors slightly to introduce life. Let tiny accents—here, holiday reds—carry narrative and rhythm simultaneously. Above all, keep each surface’s touch honest to its substance so the whole breathes.

Why the Picture Feels Fresh Today

A century on, the canvas remains vivid because it honors both celebration and privacy. It understands that a room does not need to be crowded to feel alive, and that color, rightly spaced, can bear the emotional weight of an event. Its modernity lies in restraint: instead of showing everything, it shows relations sufficient to summon the day. Viewers recognize the pleasure of standing at an open door, hearing a town enjoy itself while a cool interior holds steady.

Conclusion: A Holiday Held by a Room

“Interior, July 14th, Étretat” composes a national holiday into domestic terms. The patterned walls keep time, the open doors invite air, the balcony and sea offer civic space, and the small flags flash like musical trills. With gentle perspective, measured color, and articulate brushwork, Matisse turns a simple hotel room into a lens for public joy. The painting does not perform the celebration; it shelters it, giving viewers the best of both worlds—festive distance and intimate calm.