Image source: wikiart.org

A Portrait Built from Color and Cloth

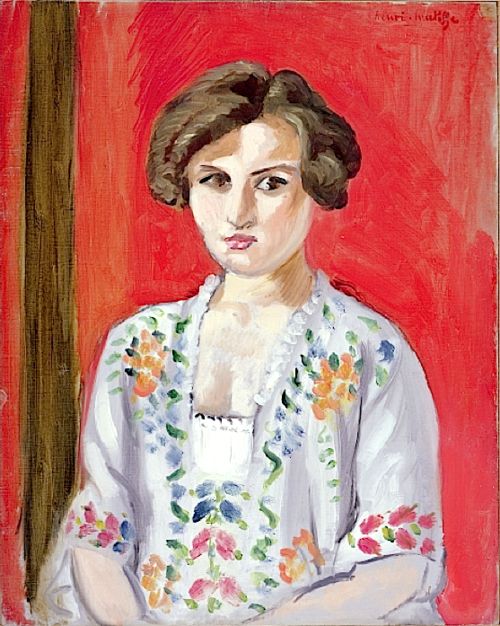

Henri Matisse’s “The Bulgarian Blouse” (1920) is a compact demonstration of how a single garment can organize an entire portrait. A young woman faces us almost frontally, her torso cropped at the waist and her head set against a saturated red ground. The embroidered blouse she wears—white cotton scattered with floral sprays in orange, blue, green, and plum—becomes the compositional engine. It declares the painting’s dominant light, establishes the mood, and, in the end, provides the most reliable path to the sitter’s character. Matisse’s postwar classicism aimed for clarity without chill; here he achieves it through the interplay of flesh, fabric, and a pulsing field of red.

Where the Picture Sits in Matisse’s 1920 Turn

The year matters. In the early 1920s, Matisse, newly committed to poise after a decade of restless experiment, used interiors, textiles, and portraits to rebuild serenity with decisive color and simple armatures. He was working in bright rooms near the Mediterranean, fascinated by how patterned cloths could both flatten and animate space. “The Bulgarian Blouse” belongs to this project. Its modernity is not loudness but concentration: a few planes, a few accents, no clutter. The artist trusted that a single strong ground and a single meaningful garment, placed correctly, could carry the full weight of a person’s presence.

Composition That Celebrates Frontal Poise

The sitter is placed close to the picture plane, shoulders square, head slightly tilted. The vertical band at left—a wooden post, a drape, or the edge of a screen—introduces a second color chord while subtly confirming the portrait’s shallow space. This frontal arrangement is not stiff; it is ceremonial. With no deep background to distract, the figure reads as a living emblem. The blouse widens the torso visually; the neckline and the scalloped edge of an undergarment lead attention upward; the face concentrates it. Matisse composes with the logic of sign rather than anecdote, reducing the portrait to a clear constellation of shapes that can be read instantly at distance.

The Red Ground as Architecture

The background’s saturated red is more than a color choice; it is architecture. It flattens the space, pushes forward, and wraps the sitter in a field of warmth that vibrates against the cool highlights of blouse and skin. Brushed in lively, directional strokes, the red is not featureless—thin and thick areas create a modest, breathing texture—but it behaves like a wall of energy that steadies the figure. Red in Matisse can be tyrannical or benevolent; here it is generous, allowing the face and embroidery to flare while keeping their intensity under control.

A Garment That Holds the Picture Together

The blouse provides the painting’s compositional rhythm and its psychological temperature. Its white ground acts as a reservoir of light. The floral sprays, loosely but decisively indicated, break the white into repeating bursts that echo the sitter’s liveliness without lapsing into decorative fuss. The soft blue stems and green leaves cool the palette; the orange and plum blossoms warm it; together they keep the red ground from dominating. Because the embroidery’s motifs are distributed evenly, the blouse feels like a measured pulse—the very quality Matisse wants a portrait to project when it seeks calm rather than drama.

Drawing Reduced to Essential Signs

Matisse’s drawing is surgical in its economy. The head is modeled with a few well-placed planes: the dark sweep of hair framing the forehead, the firm shadow under the jaw, the compact wedge that describes the nose, and the small calibrations that set the mouth. The blouse’s structure is stated with minimal seams and a clean neckline; the hands are withheld altogether, allowing fabric to stand in for gesture. This reduction strips noise from the portrait. The sitter’s identity is carried by posture, gaze, and interval, not by cataloged features.

The Face as a Calm, Self-Contained Center

Matisse refuses melodrama in the features. The eyes are level and searching, the mouth closed but not tight, the chin steady. A faint asymmetry—the right eye slightly more shadowed than the left, the turn of the lips not perfectly mirrored—keeps the face alive. He models with temperature more than with heavy value, letting cool grays and warm pinks slide across the cheeks and forehead. The result is a face that breathes. We read attention and intelligence, not theatrical feeling; a presence, not a performance.

Brushwork that Lets Materials Behave

One pleasure of the painting is how everything is made to feel itself through touch. Hair is brushed in soft, gathered strokes that hold their direction; skin is laid with shorter, elastic marks that wrap the face’s curves; the blouse is built from lively dabs and runs that mimic the way embroidery punctures cloth. The red ground is pulled in longer swathes so that it feels like a continuous plane. These differentiated touches give the eye a tactile map without over-describing. You can imagine how each surface would respond to the hand.

Color Intervals Tuned for Balance

The palette could have turned aggressive—red ground, white blouse, colored blossoms—but Matisse spaces his intensities. He keeps the white slightly warm, as if reflecting the red; he sets the blossoms in minor keys so they sing without shouting; he restrains the hair to a neutral brown and gives the skin a measured flush. A vertical brown at left tempers the red, and a few cool bluish grays around neckline and garment seams keep the composition ventilated. The classic Matisse equilibrium emerges: warmth is met by measured cool; energy is paced by rest.

Ornament as Structure, Not Accessory

The phrase “Bulgarian blouse” points to the source of the garment’s motifs in Balkan folk embroidery. For Matisse, such textiles are never ethnographic trophies; they are structural instruments. He uses their ordered repetition to stabilize the composition and their chromatic succinctness to tune the palette. The floral motifs do not illustrate an identity; they help construct a pictorial one. This is consistent with his broader practice, in which Persian rugs, Moroccan tiles, and printed fabrics provide rhythm and clarity rather than exotic flavoring.

Flatness, Volume, and the Modern Picture Plane

Although the portrait presents a living body, the space remains shallow and frank. The red field asserts the canvas as a surface; the blouse’s frontal spread discourages deep recession; the vertical band at left reads as a flat strip rather than a receding column. Yet Matisse preserves volume where it matters: the head turns gently, cheeks round, eyes sit in sockets. This balance—flat ground plus gently modeled head—delivers the modern promise of painting in 1920: truth to the surface paired with enough bodily presence to hold empathy.

The Gaze and the Social Space of the Picture

The sitter’s gaze is steady, neither confrontational nor coy. It occupies the social space a portrait proposes: a meeting without intrusion. The slight set of the lips, the raised chin, and the relaxed shoulders combine to assert composure. The blouse contributes to this sociality. Its white and floral brightness reads like a welcome, a garment worn to be seen but not to dazzle. Together, face and fabric create a climate of confident hospitality that was central to Matisse’s Nice-period humanism.

Time and Occasion Without Anecdote

No overt story attaches to the picture—no book in hand, no obvious studio prop—yet the portrait suggests an occasion. The blouse is a garment of ceremony; the red ground implies a room prepared for looking. You can imagine a brief, concentrated sitting: the model settles, Matisse positions his easel, color decisions come quickly, and the essentials are stated in one session or a handful of them. The portrait becomes a record of that concentrated present, which is exactly what makes it feel fresh a century later.

Affinities and Differences within Matisse’s Portraits of Costumes

Matisse painted many sitters in patterned garments across the 1910s and 1920s. Compared to versions with denser pattern or elaborate interiors, “The Bulgarian Blouse” is pared back. It belongs with the portraits in which a single textile becomes the star. Later, he would make the blouse itself the subject of large decorative canvases; here the textile still serves a person, not the other way around. The distinction matters: the human center keeps the painting from becoming a study of ornament and secures it as an encounter.

Edges That Tell the Story

Edges in the picture carry quiet meaning. The blouse’s neckline is crisp, insisting on the boundary between cloth and skin; the outer edge of the garment is softer, letting the figure melt slightly into the ground so the red does not feel like a pasted backdrop; the vertical strip at left has a firm, bristled outline, a material counter to the liquid red. Around the head, hair dissolves gently into the field, preventing a halo effect and preserving the portrait’s modern plainness. These edge decisions are small but decisive; they guide the viewer’s attention without drawing attention to themselves.

The Ethics of Restraint

Postwar audiences wanted stability, and Matisse provided it without sentimentalizing. “The Bulgarian Blouse” refuses spectacle. It claims the authority of a few elements placed rightly: a saturated ground, a face at rest, a garment with clean rhythms. The restraint is ethical as well as aesthetic. By not sensationalizing color or person, Matisse allows the sitter’s dignity to arise from clarity. The portrait becomes a model of attention—how to look at someone with care and make that care visible.

What the Painting Teaches about Color and Design

For artists and designers, the canvas is a concise lesson. Start with a dominant field that establishes temperature. Choose one object—here, a blouse—to carry structure and color variety. Keep the head modeled by temperature shifts rather than heavy shadow. Let ornament distribute rhythm across the plane. Offset a hot field with a cooler vertical. And ensure that every surface has a touch appropriate to its substance. These moves make an image legible from across a room and convincing at arm’s length.

Psychological Readings That Grow Naturally from Form

Because the painting is so pared down, any psychological reading must rise from its forms. The frontal pose and level gaze suggest straightforwardness; the red ground adds warmth and a trace of ceremony; the embroidered blouse implies cultural connectedness and care in dress; the absence of props resists narrative labeling. Put together, these cues offer a person who is poised, present, and unmasked. The portrait’s feeling comes less from facial drama than from the harmony of its elements; it is a picture of composure.

Material Presence and the Joy of Making

Up close, the surface reveals decisions and pleasure. Quick corrections at the collar, a flick of white on the lip, a heavier stroke along the left edge of the blouse, a translucent wash in the red that lets the ground tone breathe—these are traces of work that keep the picture alive. Matisse leaves them visible because they support the portrait’s truth. A composed sitter requires a composed surface; a living person deserves paint that remains lively.

Why “The Bulgarian Blouse” Still Feels New

The painting endures because it demonstrates how much can be done with little. Two principal planes—red and white—plus a carefully modeled head and a handful of floral notes are enough to make a presence. The decisions are timeless: frontal clarity, color used as architecture, ornament used as rhythm, drawing reduced to signs that carry more than description. Viewers feel the vitality of a person and the elegance of a system at once. That doubleness—human and structural—is the Matissean miracle.

Conclusion: A Human Presence Held by Color

“The Bulgarian Blouse” shows Matisse at his most succinct. A saturated ground gathers warmth; a floral garment distributes cadence; a steady face completes the chord. With few means he composes a hospitable space for looking, one that treats a garment not as costume but as a vehicle for clarity. The portrait is therefore both intimate and abstract: a particular person addressed directly, and a set of colors and intervals arranged with classical calm. It asks nothing sensational from the viewer—only attention—and rewards that attention with balance that feels inexhaustibly right.