Image source: wikiart.org

A Room Staged on Red

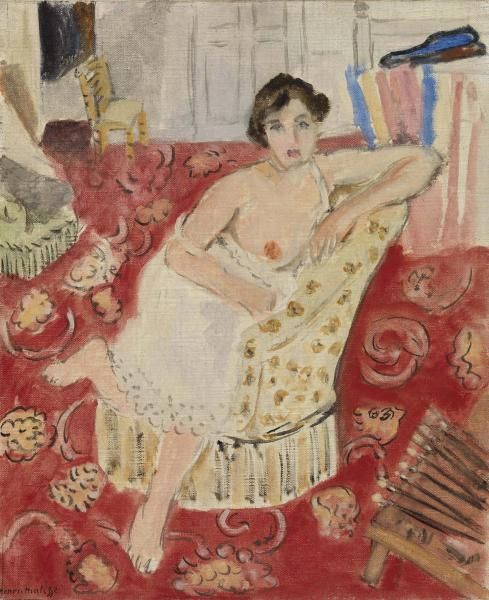

Henri Matisse’s “Red Rug” (1920) presents an interior where a single textile acts as architecture. The painting shows a young woman reclining in a pale chemise across a cream-patterned seat, set within a room whose floor is covered by an opulent crimson carpet filled with scrolling motifs and rosettes. Around her, fragments of furniture and studio objects register in brisk notations: a small chair in the back, a cushion to the left, a bundle of wooden slats or a folded screen at the lower right, and vertical stripes of color that could be stacked fabrics or props along the far wall. The field of red is so commanding that it becomes more than décor; it is the stage on which flesh, furniture, and air find their balance. Matisse condenses a world of touch—pile, cloth, wood, skin—into a lucid composition that is both intimate and architecturally clear.

The Nice Period and the Return to the Interior

The year places the canvas squarely in Matisse’s early Nice period, when he moved from the turmoil of prewar experimentation toward a postwar classicism grounded in clarity, warmth, and calm. In borrowed apartments and hotel rooms along the Mediterranean coast he painted a sequence of interiors with models, textiles, mirrors, and light washing in from high windows. Rather than pursuing analytics of form or the drama of avant-garde fracture, he sought a different modernity: one that rebuilt serenity with strong color and decisive placement. “Red Rug” is a pivotal entry in that pursuit. It connects his long fascination with ornament to a more relaxed, humane attention to bodies at rest in rooms that breathe.

A High Vantage That Flattens and Embraces

The viewpoint is slightly elevated, as if the painter stood on a low stool or took a step back and upward. This vantage compresses depth and turns the rug into a near-vertical field—almost a wall of red against which the figure is placed. The effect is modern and intentional. It acknowledges the painting’s surface instead of pretending we peer through a window. Yet the room still reads as space: the model reclines diagonally on a rounded seat; objects at the edges overlap; the back wall recedes in light grays. Flatness and volume hold a truce, a balance Matisse refined repeatedly during these years.

Composition as a Diagonal Engine

The composition revolves around a strong diagonal that runs from the lower left, across the model’s extended leg and torso, to her tilted head near the upper right center. That diagonal is countered by a second one—the slant of the patterned seat—and by the vertical pull of the far wall. The carpet’s curling motifs, placed at regular intervals, act like rhythmic brakes that keep the eye from sliding too quickly along these diagonals. The result is a controlled drift: a viewer’s gaze glides along the figure, pauses on ornament, and then resumes, always returning to the face.

The Red Rug as Structural Armature

Matisse uses the rug like a builder uses a floor plan. Its saturated field establishes the room’s temperature and secures the picture plane; its medallions and leafy scrolls, keyed in darker maroons and warm ochres, create a patterned beat that stabilizes the large expanse of red. Against this warm architecture he places cooler accents—the gray back wall, pale blue notes in the props, the ivory of the chemise—so the room never overheats. The rug’s pattern is not décor; it is composition. Its intervals decide where the figure can rest without being swallowed by color.

The Figure: Ease Balanced with Alertness

The model reclines with one arm propped on the chair-back and one leg extended, the other folded casually. The chemise slides from the shoulder, revealing the breast with a matter-of-factness typical of Matisse’s studio scenes. Her expression is open and slightly inward, more companion than odalisque. Nothing is posed for theater. The posture reads as sustained ease—an attitude that lets Matisse concentrate on relations of color and edge. Facial features are abbreviated but specific: a few dark strokes state brows and lashes; soft modeling establishes cheek, chin, and mouth. This economy lets color do the volume work while granting the body dignity through placement rather than detail.

Flesh Notes and the Climate of Light

Matisse’s skin tones here are a concert of warms and cools rather than a single “flesh color.” Honeyed pinks and peaches sit next to cooler grays in the shadows of collarbone and thigh; a small flush at the cheek and a warmer accent at the breast keep the body alive without heavy chiaroscuro. Light reads as evenly diffused—no hard cast shadows, just gentle value steps. In this climate, the chemise’s whites remain pliant and breathable, and the red rug glows rather than glares.

Patterned Seat as Counter-Form

The seat—a low, rounded bergère or ottoman—wraps the model’s torso like a shell. Its pale fabric with modest, repeated motifs plays counterpoint to the rug’s flamboyance. Matisse handles it with short, creamy strokes that catch light along the rounded edge and settle into softer tones where cloth bends. The seat’s curve echoes the arc of the model’s hip and shoulder, creating a nested harmony of forms that makes the pose feel inevitable.

Objects as Quiet Punctuation

Matisse scatters understated objects that keep the composition conversational without tipping into anecdote. A little chair in the background, a green cushion to the left, a bundle of slats or a folded screen at the lower right, and a cluster of vertical rectangles on the far wall act as punctuation marks—commas and em dashes in the visual sentence. Their colors are kept modest so they don’t compete with the figure and rug; their angles subtly reinforce the diagonals that structure the image. These inclusions ground the room in lived reality while preserving the painting’s primary argument: a figure in color space.

Color Relationships That Keep the Image Breathing

The palette rests on a triad: crimson, ivory, and warm gray, with supporting notes of gold, pale blue, and leaf green. The crimson supplies warmth and authority; ivory keeps that heat human and touchable; gray cools the upper register so the eye has somewhere to rest. Strategic accents keep the chord from sagging: the golden-yellow of the seat’s motifs, the blush of the face, the blue in the stacked props, the earth browns of wood. The colors are not simply attractive; they are placed for function. If any note were stronger—if the blues were brighter or the greens louder—the rug’s governance would falter and the figure would lose her gentle prominence.

Brushwork and Edge: Letting Materials Behave

Every zone gets its own touch. The rug’s pile is suggested by short, lively strokes and looping outlines that turn smoothly at corners; the chemise is laid in with longer, soft pulls that allow the ground to peep through, giving the cloth air; skin is made from elastic swipes that wrap form without insistence; wood and slats get blunt, brisk marks that feel carved rather than woven. Edges narrate material: a crisp contour at the knee where light meets red, a frayed line along the chemise’s lace hem, a soft boundary between hair and wall. This orchestration of touches lets the viewer sense texture without inventory.

Space Honest to the Picture Plane

Although objects overlap and the far wall is indicated, Matisse refuses theatrical perspective. The rug rises as a field; the seat’s ellipse insists on the canvas; the figure’s diagonal reads as movement across a surface rather than into a deep room. This honesty is central to the painting’s calm authority. It declares that a painting is not an illusionistic window but a set of balanced relations that can carry the full sensation of a room.

The Rug as Artistic Lineage and Personal Language

“Red Rug” inevitably recalls Matisse’s earlier “Red Studio” and his many interiors where a saturated plane—often red—absorbs and unifies the world of objects. But the present canvas is less about dissolving boundaries and more about creating a hospitable stage. The red here is warmer, softer, and tempered by pattern; it holds the figure, it doesn’t engulf her. The carpet also connects to the artist’s love of Islamic and North African textiles, which he collected and studied for their ability to organize space through repeat and rhythm rather than through linear perspective.

Figure and Textile: Equality Without Competition

A hallmark of Matisse’s Nice interiors is his refusal to let figure and décor become adversaries. In “Red Rug,” the model and the carpet share the image without vying for dominance. The rug’s repeating motifs echo in the lace scallops of the chemise; the warm red finds a gentle counterpart in the model’s blush; the golds in the seat recast the carpet’s ochres at a quieter scale. These echoes weave human presence into ornament so thoroughly that the interior feels alive, not staged.

The Gaze and the Viewer’s Position

The model’s eyes meet ours levelly. The angle implies that we stand just off to the model’s right, slightly above, a respectful distance from which to take in the room’s rhythm. There is no flirtation, no coyness, no elaborate mask of emotion. The gaze stabilizes the composition and humanizes the sea of pattern, reminding us that attention—not spectacle—is the virtue the painting most values.

Relations to Bonnard and Vuillard, Without Losing Clarity

Contemporaries like Bonnard and Vuillard also painted women amid dense patterns. Matisse’s difference is the clarity of his armature. Where Bonnard dissolves bodies and décor into atmospheric shimmer and Vuillard wraps figures in wallpapered density, Matisse builds a firm scaffold of diagonals and ovals and then lets color breathe across it. He offers legibility from across a room and pleasure at arm’s length, a dual power that makes this period so compelling.

The Weather of the Room

Although the picture contains no view out a window, it is full of air. The back wall is rendered in cool off-whites that suggest light diffused by high windows; the rug’s red, though saturated, is moderated by gray-browns that keep it from appearing self-luminous; the chemise’s whites admit ambient color, picking up hints of the room. The climate feels midday and temperate—excellent painting weather—when shadows soften and color finds its center.

The Ethics of Comfort

There is an ethic embedded in the painting’s serenity. Matisse respects ordinary comforts: a good chair, a soft rug, a relaxed posture, light that does not interrogate. He affirms that such comforts can be grounds for art rather than impediments to it. The room is not a theater for exotic fantasy; it is a place where the dignity of rest is acknowledged and staged with care.

Material Presence and the Pleasure of Making

Up close, you can track decisions. A stroke of brighter red is dragged across a darker underlayer to enliven a dull patch; a quick gray correction trims the seat’s silhouette; small retouches at the hand revise the contour without erasing the first attempt. The surface remains lively, never enameled. That liveliness becomes part of the subject: the vibrato of brushwork echoes the tactile world the painting celebrates.

Why “Red Rug” Still Feels New

The canvas remains current because it turns strong color from spectacle into structure. It shows how a single field—in this case, the carpet—can serve as armature for mood, scale, and space. It demonstrates that a figure can retain autonomy without being isolated from ornament. And it models a humane modernism that values hospitality over shock: the viewer is invited to dwell, to follow diagonals, to read intervals, to measure warmth against cool. The painting offers a method for making calm vivid.

What the Painting Teaches About Color and Design

Designers and painters can read “Red Rug” as a primer. Start with a dominant plane and give it rhythm through pattern. Counter it with a clear, pale form—a chair, a body, a cloth—so the eye has a resting place. Use small cools to ventilate large warms. Let objects at the perimeter act as soft anchors rather than distractions. And above all, let color do structural work; where it sits is as important as what it is.

Conclusion: A Figure, a Carpet, a Civilization of Attention

In “Red Rug,” Matisse composes a civilization of attention with a handful of elements: a figure at ease, a crimson carpet alive with pattern, a pale seat that echoes body and curve, and a few modest studio objects. The painting proves that serenity is not the absence of energy but the right placement of energies. The crimson field holds; the body breathes; the room hums. The viewer, like the model, is given license to rest, to look, and to feel how color and pattern can make a life of quiet intensity.