Image source: wikiart.org

An Interior That Breathes the Sea

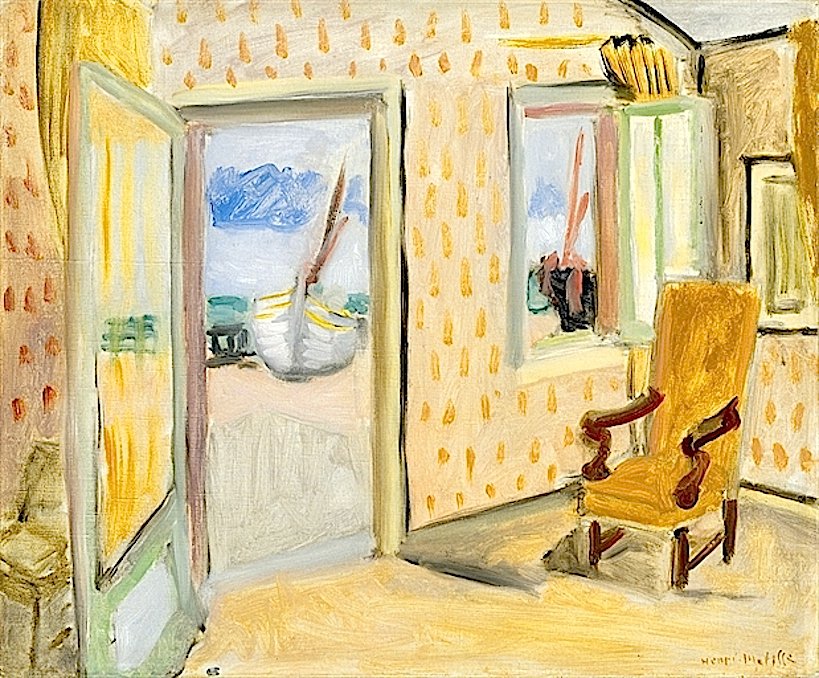

Henri Matisse’s “Interior, Open Door” (1920) is a compact masterpiece of hospitality. A sunlit room, patterned with small, leaflike dabs, opens directly onto a coastal prospect where a white boat rests in brilliant air. An armchair anchors the foreground; a sash window offers a second, smaller view to the exterior; and the open door functions like a hinge between private space and public light. With a few confident planes of color and decisive lines, Matisse turns a modest room into a vessel for wind, salt, and distance. The painting is less a depiction of things than an orchestration of relations—between near and far, warm and cool, enclosure and release.

The Nice Period and the Architecture of Calm

Painted during Matisse’s early Nice years, the work distills the goals he pursued after the First World War: clarity of structure, generosity of color, and an atmosphere of serene attention. In hotel rooms and rented apartments along the Mediterranean, he discovered a climate that supported this pursuit. Light fell evenly; walls took color without heaviness; windows framed glimpses of sea and sky. “Interior, Open Door” belongs to a family of canvases in which the domestic threshold becomes a central motif. The room is not merely where people live; it is a device that modulates light and orders perception.

Composition as a System of Thresholds

The entire image is built on the geometry of passage. The left edge is a curtain drawn back; the center is the open door; the right side presents a window like a secondary door; and in the lower right the armchair faces into the room, waiting for a body to claim it. Lines converge lightly toward the doorway’s foot, establishing a corridor of pale floor that carries the eye outdoors. Matisse’s diagonals are gentle, never theatrical. They guide rather than thrust. This restraint is crucial: the viewer feels invited to cross a threshold rather than pushed through it.

The Door as Hinge and Picture Within the Picture

The open door is a literal aperture and a compositional hinge. It divides the wall’s patterned surface while also binding interior and exterior in a single sentence. Through it we see a white hull set against bands of sea and a quick patch of mountains beneath a bright, scribbled sky. This small exterior reads like a self-contained seascape nested inside the larger interior. By placing the boat almost dead center and low, Matisse stabilizes the canvas. The boat is the punctuation mark that keeps the image from breaking into two unrelated halves.

The Window as Counter-Opening

Opposite the door, a window repeats the motif at a smaller scale. Within its frame stand two masts and a sliver of blue distance. The window’s view is not redundant; it adds rhythm and confirms that the outside world runs along the entire wall, not just at the door. The window also strengthens the sense of air moving through the room. Light enters from at least two points, softening shadows and making the interior feel permeable.

A Palette That Marries Warmth and Breeze

Color carries the mood with exactness. The interior is a field of warm creams and peaches marked by small orange-gold leaves—the pattern of the wallpaper or fabric. Against this warmth Matisse sets cool, maritime notes: the blue of distant mountains and sky, the green bands of sea, and the white of the boat whose hull holds a reflective chill. The armchair is a deep, buttery yellow with red-brown arms and legs, an object that takes the room’s warmth and concentrates it. The doorframe and window casings are a pale mint that mediates between interior heat and exterior cool. No color stands alone; each is tuned to its neighbor, achieving equilibrium without dullness.

Brushwork that Allocates a Touch to Each Zone

Every surface receives a distinct grammar of marks. The patterned wall is made of evenly spaced dabs, quick commas of paint that refuse to model depth yet make the plane lively. The chair is handled with broader, buttery strokes that suggest pile and worn gloss. The floor, especially near the door, is brushed in long, pale pulls that read as light pooling on smooth boards or tiles. Outdoors, the boat and horizon are stated with brisk, simplified notes—horizontal bands, a few strokes for the hull, a squiggle for mountain ridges. The allocation of touch becomes a tactile map: one can feel what each thing would be like under the hand.

Space Without Theatrical Illusion

Depth is clear but never insisted upon. The angle of the floor and the overlap of doorframe and wall establish recession, yet the patterned plane refuses to vanish into deep perspective. Matisse guards the painting’s surface truth. The door and window do not open onto a trompe-l’oeil world; they present another set of painted planes. This balance—volume held in check by flatness—is the signature of Matisse’s classicism in the 1920s. He treats the canvas like a room that must be proportioned to breathe, not like a corridor that one falls into.

Ornament as Structure Rather Than Decoration

Pattern is not an accessory here; it is architecture. The repeated dabs on the wall organize the interior and hold the large areas of cream in a stable pulse. Along the left edge a vertical curtain of yellow stripes reinforces the room’s height and answers the sea’s horizontal bands. The ornamental rhythm becomes a metronome for the whole picture, setting a tempo that the other forms—door, window, floor, chair—keep with. By making pattern structural, Matisse elevates the decorative into the realm of composition.

The Armchair as Anchor and Proxy Figure

The chair is the room’s counterweight to the open door. It occupies the foreground with authority, its curved arms and stout legs asserting presence without massiveness. The chair also acts as a proxy for the absent human. Its orientation suggests that someone has just risen to step through the door or that one could sit and gaze out. Matisse often used chairs this way in Nice interiors—to register the human scale without inserting a specific portrait. Here the yellow chair gathers the room’s warmth like a hearth, a domestic center that remains steady as the exterior flickers.

The Rhythm of Lines and the Quiet Engine of Perspective

Lines in the painting are elastic rather than rigid. Door jambs bend slightly; window frames flex; the floor’s seams slant softly. This flexibility keeps the composition lively and friendly. Perspective operates as a quiet engine—not a set of hard rules but a group of tendencies that make the space credible. The viewer trusts the room precisely because it is not mechanically plotted; it yields to the eye the way real rooms do.

Light as a Climate of Openness

There are almost no cast shadows, yet the room is full of light. Matisse evokes illumination through value steps and through the steady, pale temperature of the interior colors. The open door is a vertical column of brightness; the window’s reveal carries a wash of cool light; the floor near the threshold blooms with thin, milky strokes. Light is a climate here—a continuous condition that saturates planes—rather than a spotlight that isolates objects.

The Exterior as Promise, Not Narrative

The world beyond the door is purposely unspecific: a dock, a boat, bands of sea, low mountains, a patch of sky. There are no figures, no story of departure or return. This restraint matters. It keeps the painting from becoming anecdote and allows the exterior to function as promise—air, movement, possibility. The sea is a tonic color chord that freshens the room rather than a plot that distracts from it.

Balancing Nearness and Distance

One of the painting’s deep pleasures is how it balances intimacy with openness. The room’s nearest objects—the chair, the patterned wall, the threshold—occupy the viewer’s body space; the sea and sky open the chest and lengthen the breath. Matisse composes that physiological shift. The eye rests on the chair’s soft curve, then moves through the cool rectangular aperture to the clean horizon. You experience the painting not merely as an image but as a sequence of bodily sensations: sitting, standing, stepping outside.

Dialogue with Earlier Windows and Doors in Art

Open doors and windows are a venerable motif—from Dutch interiors to Romantic seascapes and Impressionist balconies. Matisse’s contribution is to treat the threshold not as a means to show off perspective or distant detail, but as a tool for ordering color. Where Vermeer might anchor a narrative with the fall of light through a casement, Matisse anchors a harmony of warm interior and cool exterior. Where Monet multiplies atmospheric nuance, Matisse condenses it into bands and patches that read instantly and remain fresh at distance.

Affinities with His Odalisque Rooms

Across the decade Matisse would evolve these interiors into more elaborate odalisque scenes, full of patterned textiles and reclining models. “Interior, Open Door” is a leaner cousin to those works. The patterned wall foreshadows the riot of later motifs; the yellow chair signs the artist’s affection for furniture as companion; the framed views outward anticipate windows filled with terraces, palms, and sea. Yet the present painting’s restraint—no figure, few objects—allows a special calm. It is the grammar of those later rooms stripped to its essential syntax.

The Ethics of Hospitality

There is a quiet ethic at work. The painting is hospitable: it invites you in and then invites you out. Nothing is hoarded; nothing is forced. The open door suggests that interior beauty is not a possession but a passage, that domestic life gains richness when it exchanges air with the world beyond. Matisse’s humanism resides in such unobtrusive propositions. He composes rooms that make space for looking, and in doing so he proposes a way to live.

Reading the Picture Through Its Edges

Edges frame the painting’s argument. On the left, the thick yellow curtain acts like a slow door beyond the open door, confirming that interiors require layers of thresholds. Along the bottom, the floor gathers the light to push it toward the viewer, as if encouraging you to step in. Near the top, a quick tuft of yellow above the window—perhaps a bunch of brushes or flowers—lifts the eye and prevents the composition from sinking toward the floor. The edges are not afterthoughts; they are active participants in the image’s balance.

Material Presence and the Pleasure of Paint

Seen up close, the canvas is alive with the pleasures of making. Broad strokes turn buttery in the chair; thin washes at the doorway let the ground tint cool the light; a single loaded line fixes the boat’s gunwale; quick, varied dabs establish the wall’s semiregular pattern. Matisse allows evidence of the brush to remain visible because it supports the sensation he wants to transmit. A room that breathes needs paint that breathes—the surface must not congeal into enamel.

A Picture That Teaches by Example

For designers, photographers, and painters, the canvas is a concise lesson. Warm interior plus cool exterior yields depth without tricks; pattern can stabilize large fields; a single strong object in the foreground can anchor a view; repeated apertures create rhythm. Most importantly, color is a structural force. The mint doorframe, the buttery chair, the sea’s bands, and the peach wall are not moods layered on top of drawing; they are the drawing.

Why the Painting Feels Fresh a Century Later

The work endures because it treats everyday facts—door, chair, view—as inexhaustible. It shows how attention, not novelty, makes a space modern. Its clarity allows multiple readings: domestic comfort, anticipation of travel, the union of shelter and air. And its means remain legible from across a room and at arm’s length. Many paintings depend on detail that collapses at distance; this one depends on relations that sharpen as you step back and hold as you move in.

Conclusion: A Room, a Door, a Horizon

“Interior, Open Door” is a hymn to placement. A patterned wall, a yellow chair, a mint frame, a banded sea, and a white boat are enough to hold a horizon steady and to let a viewer breathe better. Matisse composes a domestic scene that is also an image of freedom. The open door is not simply an object in a room; it is the painting’s verb. It allows light to enter and invites the eye to depart, then to return, carrying air. In that oscillation—between inside and out, rest and prospect—lies the picture’s lasting, lucid grace.