Image source: wikiart.org

A River Scene Composed from Light and Rhythm

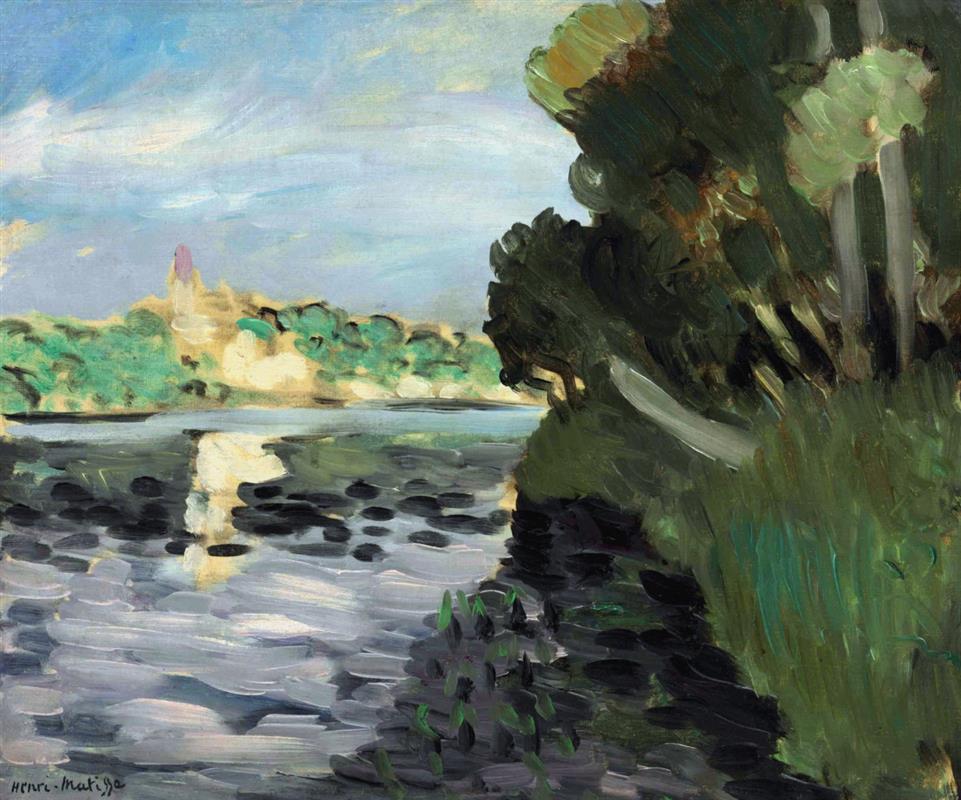

Henri Matisse’s “Banks of the Seine at Vétheuil” (1920) turns a familiar French landscape into a lesson in how few relationships are needed to make a world. A broad sky drifts over a dark, reflective river; a sunstruck village sits low on the far bank; and at the right a dense stand of trees thrusts forward like a single green body. The painting is both spare and abundant. It withholds descriptive detail, yet it supplies everything a viewer needs to feel the day—breeze in the leaves, glare on water, coolness in the shade. Matisse arranges the scene as a balanced chord of sky, water, and foliage, letting brushwork and value carry the sensation of place.

Vétheuil in the Painter’s Itinerary

Vétheuil, a town on a bend of the Seine northwest of Paris, was a celebrated motif long before Matisse set up there; Claude Monet painted its church and riverside repeatedly in the late 1870s. When Matisse visited decades later, he did not attempt to outdo Impressionist shimmer. Instead, he pursued the postwar project that marks his 1918–1922 work: clarity through reduction. The picture bears the signature of that ambition. It is not a report of changing light or a catalog of local incident; it is a stable structure that keeps the day’s weather and color alive inside a strict compositional frame.

The Composition’s Three-Field Armature

The canvas divides into three fields. The upper half is almost entirely sky, a cool expanse brushed in long, slanting bands that drift leftward. The lower left is water, a broad plane broken by horizontal pulls and clustered dark ovals that read as reflections. The lower right is a thick wedge of riverbank—grass, trunks, and overhanging foliage—thrusting diagonally into the picture.

This armature is simple and decisive. The tree mass at right acts as a counterweight to the open sky, pressing forward to affirm the picture plane. The river runs like a belt between near shade and far brightness, a moving middle register that glues the halves together. And along the distant bank a bright strip of village and trees, punctuated by a soft red spire, stabilizes the horizon and sets the painting’s tonal key. The eye follows a loop: in through the shaded bank, across the river’s reflective surface, up to the sunlit far shore, and back through the sky’s slow bands.

A Palette Tuned to River Weather

Color here is economical and exact. The sky is a milky mixture of blue, pearl gray, and a touch of lemon where light gathers; the river carries cool violets and slate greens with streaks of white; the near bank is deep green-black edged by vertical strokes of brighter green and olive; the far bank is a warm strip of yellow-cream and mint green. Nothing is saturated to the point of spectacle. Instead, small temperature shifts do the work: cool sky against warm distance, warm distance against cool water, cool water against the dark, insulating greens of shade. The picture breathes because these intervals are precisely spaced.

Brushwork that Assigns a Touch to Every Zone

Each part of the landscape receives its own grammar of marks. The sky is laid in with broad, elastic strokes that leave slight gaps and overlaps, letting the ground peep through and simulate high air. The river is constructed with horizontal pulls and broken, oval notes—calligraphic dabs that read as patches of reflected foliage. The near bank is built from heavier, curving strokes that stack into leaf masses; on the trunks, broader, moist swipes settle in a single pass to declare the verticals. This allocation of touch is not decorative; it’s descriptive at the level of sensation. Air is light and layered; water is dragged and sheened; vegetation is thick and sprung.

Water as a Second Painting Within the Painting

Matisse has always been alert to the way water turns the world into a moving collage. Here he treats the Seine as a second canvas set flat beneath the scene. The dark ovals are not stones or lilies; they are fragments of reflected tree mass caught on a rippled surface. The long, pale streaks cut across them like edits, traces of wind that breaks the reflection into film-like frames. Center-left, a vertical tower of pale strokes marks the bright village mirrored in the water, a quick, luminous column that completes the circle between far shore and river. This strategy makes the water feel active without resorting to wave-by-wave description.

The Right-Bank Thicket as a Single Figure

The block of foliage at right is handled as if it were a single figure leaning into the picture—a device Matisse often used to set a dominant mass against a field. The trunks function as bones; the fan-shaped clusters of strokes stand in for muscle and leaves. The negative spaces carved between these clusters are as important as the painted forms: irregular flashes of sky and river that keep the thicket breathable. The effect is sculptural without heaviness, and it gives the viewer a bodily anchor—a near, shady place from which to look across.

Edges that Tell the Story of Matter

Edges carry narrative information. Where the bright distance meets the sky, transitions are soft and warm, hinting at sun haze. Along the river’s top edge, a few straightened pulls give the water a planar authority. In the thicket, edges are torn and frayed, stating the fibrous character of vegetation. Even the small plant at the lower center right, painted with quick upright dashes tipped in green, has edges that convey delicacy against the water’s drag. These shifts teach the hand what each thing would feel like: plastery village walls, slick water, springy leaves.

Space Without Theatrical Illusion

The painting has depth, yet it maintains the integrity of the surface. Matisse avoids a plunging viewpoint, keeps the horizon comfortably high, and lets the near bank intrude as a flat wedge. The far village is a ribbon rather than a receding townscape; the river runs horizontally; the sky’s bands reaffirm the canvas as a plane. The result is modern classicism: a believable space that remains a picture rather than a peephole. In this respect Matisse continues the project he pursued in Nice interiors during the same years—holding volume and flatness in a calm truce.

Human Presence Registered as Scale, Not Anecdote

No figure appears, yet the village enters as witness and measure. The small spire—plum against mint—sets human scale across the water and calibrates all other distances. Matisse refuses to decorate the banks with boats or walkers. The absence is not austerity; it is a way of letting the painting’s main actors—light, water, foliage—carry attention. The town across the way becomes a place to imagine rather than a story to read.

Dialogue with Monet and the Impressionist River

Because Monet’s Vétheuil is canonical, any new treatment of the site is a conversation. Monet built the scene out of countless shimmering touches and tracked specific hours. Matisse replies with fewer, larger relationships. He trusts the resistance of paint, not the multiplication of flecks, to deliver light. His river does not glitter; it reads as a continuous, reflective field. His sky is not broken into vaporous dots; it sweeps in planks of color. The differences are instructive: both painters are faithful to perception, but Matisse distills where Monet proliferates.

Time of Day and the Weather of Work

The illumination suggests late morning or early afternoon with thin cloud: the sky is high, the far bank is sunlit, the shaded right bank is cool but not dark. It is a weather of work, the kind that permits a painter to articulate shapes without the distraction of hard shadow or blinding highlight. Such conditions suit Matisse’s structural aims. He can state the big relationships—the weight of the thicket, the breadth of the river, the placement of the village—and let subtle color shifts handle atmosphere.

The Sound and Temperature the Image Conveys

Though silent, the painting carries a soundscape: leaf-rustle where the strokes cluster; hush on the water where strokes run smooth; faint village activity where the far bank warms. Temperature is legible, too—the near chill of shade, the tepid warmth across the water, the coolness that sits in the sky’s light grays. These sensations arrive because brushwork and value have been tuned to them, not because anything is mimetically detailed. Matisse paints how the place feels before he paints what it is.

The Ethics of Reduction

“Banks of the Seine at Vétheuil” enacts an ethic Matisse refined after the war: say no more than the structure requires. He reduces the village to a luminous strip, the river to a few systems of marks, the thicket to voiced clusters, the sky to long bands. But because each reduction is exact, the whole is generous. The viewer’s imagination is invited to complete what is implied—sun angle, depth of water, soft breeze—and in doing so becomes a collaborator. This is not minimalism; it is confident sufficiency.

Relation to the 1920 Landscapes and Coastal Studies

The canvas belongs beside Matisse’s coastal pictures from the same year—Étretat’s cliffs, boats hauled on shingle, women resting on the beach. Those works also hinge on a few large masses kept in poised relation. Here the cliff is replaced by a thicket, the sea by the river, the beach by the opposite bank. Across subjects, the method endures: establish an armature, assign touches to zones, let color intervals carry mood. The consistency reveals how he translated lessons from still lifes and interiors—where a single vase or sofa could organize a room—into outdoor space.

Interpreting the Image: Rest, Passage, and Measure

It is easy to see the painting as a simple idyll, yet it also sustains richer readings. The shaded bank where we stand is rest; the river is passage; the sunlit village is measure and destination. The reflection that runs like a pale pillar down the water suggests how the world doubles and moves as we look. None of this is insistently symbolic. It is simply how river landscapes work when composed with care: they organize stillness and motion into one readable sentence.

Why the Painting Still Feels New

The picture’s freshness lies in its durable clarity. Many landscapes show more things; few make relations this legible. Because the composition is so well balanced—big mass at right, broad sky, calm band of water—its parts can afford to be open, even sketchy. The viewer receives structure first and specifics second, which is why the image remains convincing at a distance and rewarding at close range. It is a model of how to condense perception without drying it out.

Conclusion: A River Held in Necessary Relations

“Banks of the Seine at Vétheuil” is an argument for the sufficiency of placement. A block of trees, a band of river, a sunlit village, and a deep, manageable sky—set them in right relation and you create both a site and a mood. Matisse’s brush never fusses; it states. His color never shouts; it balances. The canvas is not about picturesque detail but about the conditions that let looking become easy and alert. In that balanced state—clear, breathable, and complete—the painting finds its lasting authority.