Image source: wikiart.org

A Coastal Image Built from Wind, Stone, and Three Figures

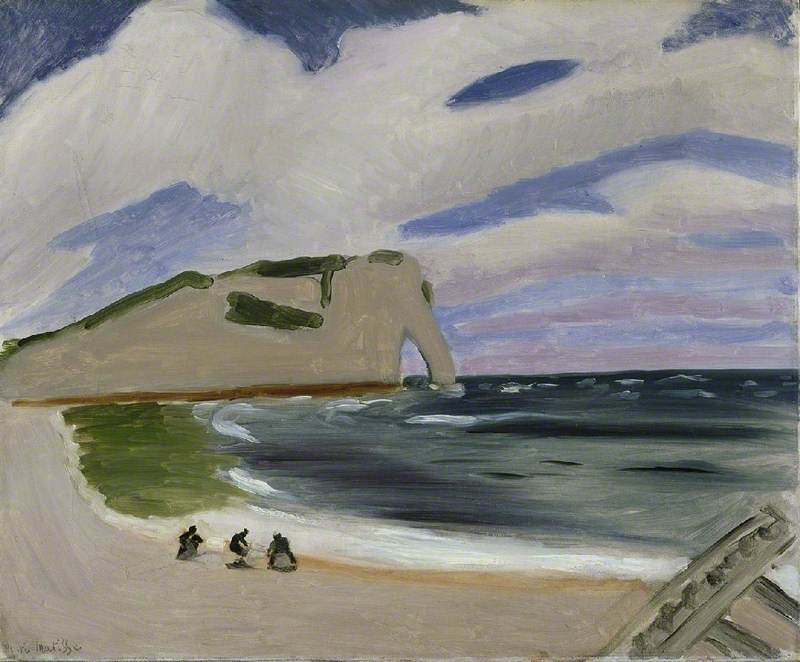

Henri Matisse’s “Women on the Beach, Étretat” (1920) compresses an entire coastal world into a handful of sure relations: the chalk arch that makes Étretat famous, a banded and wind-swept sky, dark water cut with white spume, and three small figures placed on the sand like punctuation marks. The picture is neither anecdote nor spectacle. Its power lies in how the artist measures immense things—cliff, sea, weather—against the nearness of human presence. In a single glance the viewer grasps both the monumentality of the headland and the fragile rhythms of life along its shore.

Étretat After the War and Matisse’s Pursuit of Clarity

Painted in 1920, the canvas belongs to a postwar moment when Matisse sought compositional calm and structural lucidity. He returned repeatedly to the Normandy coast, a site already inscribed in modern French art by Courbet and Monet. Rather than chasing the drama of crashing surf or the flicker of light minute by minute, he simplified. The headland becomes an almost abstract wedge of chalk capped with green; the sea is a dark field with a few long strokes to state its motion; the sky is organized into broad, blowing bands. This reduction is not a retreat from reality; it is a way to reveal the architecture of the place—the armature on which experience rests.

The Composition Hinges on Two Long Diagonals

The painting is built on a pair of commanding diagonals that meet near the arch. One is the shoreline sweeping from the lower right up toward the rock; the other is the underside of the headland thrusting outward over the surf. The diagonals create a hinge that turns the viewer’s attention from beach to water and back again. The three women sit just inside this sweep, establishing a scale for everything that follows. Their placement also slows the eye before it slides to the dark sea, allowing the foreground to register as a lived surface rather than a mere base for the famous cliff.

A Sky That Carries the Wind

The sky is not a neutral backdrop. It arrives as long, scrolling strokes of pale gray, lilac, and blue, angled as if the wind were combing them into bands. These ribbons repeat the shoreline’s curve and echo the sea’s horizontal pull, unifying the image from the top down. Matisse’s clouds are not modeled volumes but sheer veils whose internal tonal shifts suggest height and movement. The decision keeps the sky light and breathable, the correct counterweight to the heavy headland without sacrificing the sense of weather moving through the scene.

The Headland as Sign and Mass

Matisse reduces the cliff to an unequivocal sign: a blocky plate of chalk cut by an arch, its top patched by olive-green vegetation. The contour is so direct that it functions almost like a letter in an alphabet of forms. Yet within that directness he lets subtle variations of gray-brown and cream play across the rock’s face, implying shadow and geological layering. The bottom edge of the cliff is stated with a single emphatic stroke, a warm line that separates land from water and fixes the rock in space. By refusing fussy description, Matisse convinces us of mass more completely than a catalog of cracks ever could.

Dark Water and the Line of Spume

The sea here is a field of near-black green, brushed in long horizontal pulls that keep it coherent. Against this darkness thin lines of white ride the surface, describing both the shallows near the beach and scattered caps farther out. These light strokes are small in number but critical to the picture’s rhythm: they articulate the water’s tempo and tie it visually to the clouds’ bands. Because the sea is so simply built, its weight presses satisfyingly against the beach. The viewer senses depth and cold without needing a detailed inventory of waves.

The Beach as a Plane of Work and Pause

The beach occupies a triangular forefield of buff sand laced with cool green where the water has darkened it. It is not over-described; it is a surface to inhabit. Near the center left, three women sit or crouch in conversation or rest, their forms simplified to dark notes with lighter caps. They locate the painting’s human temperature. The viewer reads their scale instantly and, because of their modesty, feels that the scene is observed rather than staged. The placement suggests a pause in a day of collecting, mending, or simple social exchange—habits as cyclical as the tide.

Human Presence Scaled to the Coast

Matisse’s figures rarely operate as narrative protagonists in these coastal canvases; they are measures and witnesses. The three women provide a local tempo, a human duration that lives alongside the geological time of the headland and the meteorological time of the wind. Their dark shapes echo the tones of the sea, while the small touches of light on their caps rhyme with the foam at the water’s edge. Through these correspondences the painter folds the human into the broader cadence of place without diminishing either.

Color Economy and the Breath of Maritime Light

The palette is lean and coastal: chalky grays and creams for the rock, olive and moss for the sparse vegetation, deep green-black for the water, and a sky that alternates pale gray with violet and blue. The sand stays warm but low in saturation so that the headland’s edge and the wave lines can speak clearly. This economy grants the impression of sea air—transparent and cool—without resorting to glittering hues. Matisse understands that in such weather color is carried by value relationships and subtle temperature shifts rather than by saturation alone.

Brushwork That Separates Zones by Touch

Each zone of the painting has its own tactile vocabulary. The cliff’s paint is slightly opaque and dry, leaving a gritty skin that evokes chalk. The sea is stroked more fluidly and horizontally, leading the eye across its breadth. The sky is scumbled, its bands dragged in thin layers that let the ground tint mingle with the paint and create aerial lightness. The beach is brushed broadly enough to feel flat but with variations that suggest damp and dry. These changes of touch let the viewer sense how each part of the coast would feel under the hand—abrasive, slick, airy, yielding.

Space Without Theatrical Illusion

Depth is clear but measured. There is no extreme perspective, no plunging vantage, no dramatic overlap. The headland’s long underside establishes a deep corner where sea meets rock, yet the image insists on its surface truth. The horizon is a level band; the clouds are laid as stripes; the beach reads as a near plane. By keeping the construction frank, Matisse aligns natural space with the discipline of the picture plane, a hallmark of his work in the 1918–1923 years.

Dialogue with Courbet and Monet at Étretat

Paintings of Étretat inevitably converse with predecessors. Courbet emphasized the weight of matter and the crash of waves; Monet multiplied the site through changing weather and hours. Matisse’s statement is different. He does not dramatize event or chase optical permutations. Instead, he composes a stable, memorable sentence from a few large forms. In doing so he renews the motif for modern eyes, proving that restraint and clarity can be as contemporary as virtuoso flourish.

The Wind’s Direction and the Viewer’s Body

The angled clouds and the tilt of wave-edges imply a wind driving from left to right, a force that the body recognizes. This implication organizes a physical empathy in the viewer: shoulders lean, eyes narrow, breath alters. The women’s seated posture, low to the ground, reads as a local response to that force. Matisse often structures his compositions to activate such somatic knowledge, allowing a viewer to feel the weather rather than only see it.

The Headland’s Arch as a Frame and a Pause

Étretat’s arch is famous for how it frames a wedge of sea. Here it is smaller than one might expect, an aperture rather than a spectacle. Placed off center, it functions as a pause in the rock’s mass, a literal hole that gives the picture room to breathe. The arch also works abstractly as a notch that the horizon slips into, locking sea and land together. Even at this condensed scale, the arch’s curvature introduces a single rounded form among the painting’s prevailing diagonals, a gentle counter-shape that keeps the image from becoming purely rectilinear.

The Foreground Board and the Logic of the Edge

At the lower right, a set of planks or a ramp enters the frame at an angle. Their appearance is abrupt but purposeful: they articulate the painting’s edge and repeat the long shoreline diagonal, forming a visual echo that keeps the viewer’s eye inside the composition. The boards are also a practical sign, evidence of a working beach where boats come and go. Matisse compresses such evidence into the smallest possible cue, trusting a few strokes to state an entire maritime economy.

Time Scales Layered into a Single Day

The painting layers three temporal registers. The headland speaks of geological time—sedimentation, erosion, change too slow to witness. The sea and sky speak of cyclical time—tides, wind shifts, hours. The women speak of daily time—tasks, talk, rest. Matisse harmonizes these scales without drama. Their coexistence is the painting’s quiet argument: a life on the coast unfolds within larger rhythms one cannot control, and this condition is neither tragic nor heroic but simply true.

Material Presence and the Honesty of Paint

Seen up close, the painting refuses illusionism. Short gaps of canvas show through thin passages; brush ends leave bristled signatures along cloud edges; a dragged stroke breaks at the crest of a wave. Such evidences remind the eye that the scene is a surface event. This honesty does not reduce the sensation of place; it supports it. The viewer experiences two realities at once—the coast and the paint—and their engagement becomes the work’s central pleasure.

Women as Witnesses Rather Than Ornaments

The title identifies the figures by gender, but Matisse refuses to turn them into picturesque types. They are neither costumed fisherwomen of folklore nor elegant visitors. They are simply people whose presence confirms that this place is inhabited. Their dark tones keep them from popping forward as anecdote; their smallness gives them dignity rather than sentimentality. The painting’s humanism lies in this modesty: a belief that the measure of a world can be found in how ordinary figures occupy it.

A Modern Classicism of Placement

What makes the picture feel modern is not novelty of subject but the exactness of placement. Each large shape—beach, sea, cliff, sky—is tuned to the others so that no region demands bravura to hold attention. The image is a balanced chord. This classicism of placement, achieved with contemporary brevity of mark, is the postwar Matisse at his clearest. It is painting as a set of necessary relations, nothing more and nothing less.

Why the Image Remains Fresh

The canvas endures because it captures a felt world with frugal means. A few diagonals structure space, a handful of colors declare weather, a trio of figures calibrates scale, and the famous cliff becomes a calm sign among other signs. The viewer senses wind and salt and the low roar of water while enjoying the serenity of the composition. The work’s lasting relevance lies in this double gift: it respects both the place and the picture.

Conclusion: A Coast Composed, A Day Kept

“Women on the Beach, Étretat” is a distilled coastal meditation. The headland’s mass, the sea’s dark plane, the sky’s streaming bands, the three seated figures, and the angled planks at the frame’s edge form a complete, lucid sentence. Matisse lets structure do the work of description and lets small human presences grant measure to grandeur. The painting suggests a truth he pursued throughout the 1920s: when forms are placed with care, a viewer breathes the same air as the scene and believes in its quiet reality.