Image source: www.wikiart.org

A Luminous Interior Balanced on Red

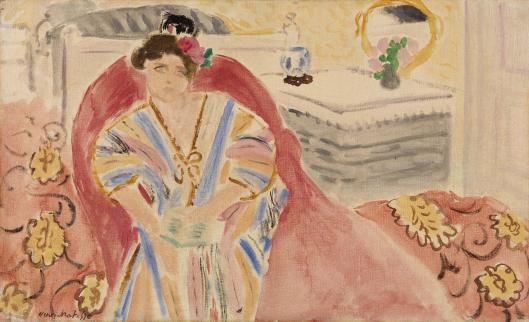

Henri Matisse’s “Woman on a Red Sofa” (1920) belongs to the remarkable run of interiors he produced in Nice after the First World War. The scene is intimate and deceptively simple: a model settles into a deep red sofa, wrapped in a striped robe whose pastel bands catch and diffuse the room’s Mediterranean light. Around her, a console table holds a cup, a small vase, and a round mirror whose bright rim turns the background into a secondary picture. Nothing dramatic occurs, yet the canvas hums with decisions about color, edge, and pattern. The red sofa is not merely furniture; it is the platform on which Matisse rebalances the age-old problem of figure in interior space, reducing drawing to essentials so that color and placement can do the heavy lifting.

The Nice Period and the Return to Light

Matisse moved his practice south around 1917 and, for more than a decade, explored rooms washed with warm light, models at ease, and textiles as protagonists. This turn was not a retreat from modernity but a different answer to it. After the turbulence of Fauvism and Cubism’s structural experiments, he sought clarity and calm. Nice offered a soft, even illumination that allowed tones to gather without harsh shadow. “Woman on a Red Sofa” distills that climate: there is brightness but little glare, warmth without heaviness, and an atmosphere that lets color speak in long, unbroken phrases. Within this climate, the figure becomes less a portrait of a person than a node where interior light, textile pattern, and human presence converge.

Composition as a Theater of Two Curves

The canvas is organized around two interlocking curves. The first is the enveloping arc of the sofa’s back and arm, painted in a raspberry red that flares along the edges and sinks toward the cushion. The second is the oval halo suggested by the round mirror above the table, whose golden rim repeats the sofa’s curvature in a smaller key. Between these two arcs the woman’s robe falls in vertical bands, a cascade of blues, pinks, and creams that stabilize the composition with gentle gravity. The eye moves in a loop: from the woman’s face to the mirror, down the diagonal of the table, across the sofa’s arc, and back to the patterned seat cushion in the foreground. The result is a circuit that feels continuous and unforced, as if the room’s shapes were quietly rhyming with one another.

The Red Sofa as Structural Anchor

Red in Matisse is both a color and an architecture. Here the sofa supplies mass, temperature, and mood. Its broad field anchors the figure, but it also pushes forward, flattening the space in a way that keeps the painting honest about its surface. The red’s edges are not uniformly crisp; they fray where cloth would fold and harden where wood would frame. This varied contour gives the sofa a lived quality and keeps the color from turning into a mere decorative block. Against the sofa, all other hues are calibrated: the robe’s cool bands cool further, the skin notes warm, and the background whites adopt the faintest blush. The sofa is the tuning fork for the entire palette.

A Robe That Paints the Air

The model’s striped robe is the painting’s most articulate device. The stripes are not simply pattern; they are a way to grade light. Soft blues and lilacs carry the cool of the room; pinks and creams relay reflected warmth from the red upholstery; narrow strokes of ochre and a few disciplined lines sketch the robe’s folds without insisting on anatomy. Matisse lets the robe do what shadow used to do in classical painting: define volume and situate the figure in space. But because the robe’s shadows are color rather than brown or black, the figure feels suffused with air rather than carved from it.

Drawing Reduced to Essential Signs

One of the pleasures of the painting is how little drawing it needs. The face is a supple set of abbreviations—an eye indicated by a small wedge, a mouth by a short stroke, the hair massed as a single dark shape pricked by a pink flower. Hands are suggested rather than modeled, as if Matisse trusted the viewer to complete their shape once their position had been stated. Jewelry is a calligraphic loop. This reduction clarifies attitude: the sitter is settled, forward-leaning, engaged with the room more than with a distant viewer. The economy of signs is not laziness; it is a wager that the right few marks can carry more grace than many.

Patterns That Behave Like Characters

The upholstery’s scrolling motifs, the robe’s stripes, the floral accent in the hair, and the mirror’s roundness behave like characters on a stage. They converse in the language of repetition and contrast. Curlicues in the seat cushion counter the robe’s vertical bands; the mirror’s ring answers the sofa’s arc; the sprinkling of small objects on the table—the cup, the vase—introduce minor notes that keep the eye from skating too quickly across the pale ground. Everything feels placed rather than piled. Matisse arranges pattern not as ornament but as structure, letting it participate in the picture’s geometry.

The Mirror and the Question of Gaze

Mirrors in Matisse’s interiors rarely serve only as props. They alter the traffic of looking. Here the round mirror, slightly tilted, does not reflect the woman’s face; instead it registers a zone of brightness and a hint of green from a small plant, adding a second center of light high in the composition. The choice matters. By refusing the easy reflection, Matisse keeps the woman’s presence grounded in the here and now of paint rather than in a narrative about self-regard. The viewer’s gaze is not shuttled to a doubled image; it stays with the physical facts of sofa, robe, table, and air. The mirror becomes a lamp of sorts, a circular patch of radiance whose color helps balance the large field of red below.

Light Without Shadows, Space Without Depth Tricks

The painting describes space, but it does not rely on cast shadows or hard perspective to do so. Light is distributed; edges are softened where necessary; planes are kept in simple relations. The table is a set of stacked rectangles; the wall is a pale, vaporous field; the sofa creates foreground by sheer color authority. This disciplined simplification allows the painting to breathe. Space is present, yet the picture keeps announcing that it is a surface. The two truths—volume and flatness—coexist without quarrel.

Material Surface and the Pleasure of Touch

Viewed up close, the painting reveals how decisively it is made. Many passages are thin, brushed so lightly that the weave remains visible; others, such as the sofa’s edge or the floral scrolls, carry a touch more paste to catch actual light. The face is handled with tender hesitations, the robe with steady, parallel strokes, the table with scumbles that almost erase themselves. These material choices convert ordinary objects into sensations: velvet becomes a gentle weight of pigment, porcelain becomes a small, opaque brightness, and air becomes the near-transparency of the ground.

A Modern Interior Without Anxiety

Much early-twentieth-century art treats interiors as stages for psychological friction. Matisse, by contrast, cultivates serenity without banality. Everything about the room suggests habit and pleasure: a familiar seat, a robe that trades stiffness for languor, a table with daily objects, a mirror recording daylight. The woman’s posture is attentive but unguarded. Even the red sofa—so intense a color—feels benevolent because it is modulated by the pale environment. The painting proposes a modern interior where living well means seeing well, and where harmony is achieved by placement rather than by narrative resolution.

Dialogue with Earlier Domestic Painters

Matisse’s interior converses with the domestic modernism of artists like Bonnard and Vuillard, yet his method and aim differ. Bonnard dissolves form into atmosphere and intimacy; Vuillard cloisters figures within wallpapered density. Matisse, by comparison, clarifies. He removes picturesque clutter and leaves the least number of relations needed for a full experience. Where others weave fabric and figure into a fog of pattern, he gives each element a strong silhouette and lets color bind them. The result is legible at distance and rewarding up close, a hallmark of his Nice period.

The Model as Co-Author of Calm

Though unnamed here, the model is not a passive ornament. Her forward lean, joined hands, and slight turn toward the viewer help establish the room’s tempo. She acts as hinge between the sofa’s lap of red and the table’s pale plateau. The flower tucked near her hair and the pendant at her chest introduce small focal points that repeat the circular motif of the mirror. Through these signs, the model participates in the picture’s structure, co-authoring the calm Matisse aims to fix.

Ornament, Identity, and the Everyday Theatrical

Ornament in the painting is neither exotic fantasy nor bourgeois display. It is the everyday theatrical of a room prepared to welcome light: patterned fabric inviting touch, a robe whose stripes lend dignity to relaxation, a mirror that brightens like a window within a wall. These ornaments do not assert a specific social identity so much as they assert the value of attention. By painting them with care and giving them compositional roles, Matisse suggests that a life made of such things—useful, chosen, well placed—can be a cultured life.

Color Relationships that Carry Emotion

The emotional tone of the canvas arises less from a depicted story than from color intervals. Red, pink, and cream create warmth; blue-violet strokes in the robe insert coolness that keeps the warmth from stifling; small greens in the bouquet and mirror offer a fresh counterpoint. The balance is tilted toward comfort, but not to languor. The cools prevent drowsiness; the warms prevent chill. If the painting feels companionable rather than ecstatic, it is because these intervals are tuned for steadiness.

The Ethics of Reduction

“Woman on a Red Sofa” demonstrates Matisse’s conviction that less, placed rightly, is more. He declines anatomy where it would slow the image; he edits the background to an essential set of planes; he trusts a single field of red to shoulder the room’s weight. This ethic does not simplify experience; it distills it. By clearing away the inessential, he makes room for the viewer to recognize textures of living—the way cloth falls after a long sit, the way a mirror returns light to a shadowed corner, the way a saturated color can calm when well balanced.

A Pictorial Conversation with His Odalisques

Within a year or two of this painting, Matisse’s odalisque theme would take fuller shape, with models in patterned garments reclining amid screens, plants, and mosaics. “Woman on a Red Sofa” can be read as a gentler sibling to those scenes. The robe and sofa hint at the pleasure of textiles and the stage of repose, yet the atmosphere remains domestic rather than exoticized. The focus is not fantasy or costume but the grammar of interior form. The painting thus serves as an important hinge in the 1920–1921 transition: the decorative ambition grows, but the language stays lucid.

Why the Painting Still Feels New

The painting’s freshness lies in the ease with which it joins hospitality and rigor. It welcomes the viewer with familiar objects and readable color, then rewards prolonged looking with exact relations of curve and plane. The image is calm yet not complacent, intimate yet not confessional. As contemporary viewers, we recognize the room’s pleasures—a comfortable seat, a soft robe, a table washed by daylight—and we marvel at how few marks are required to make them present. The work reminds us that painting’s power does not depend on theatrical invention; it depends on the rightness of choices made on a flat surface.

Conclusion: A Room Composed, a Mood Kept

“Woman on a Red Sofa” holds a mood as surely as it holds a figure. The red sofa anchors, the striped robe breathes, the mirror brightens, and the small objects punctuate. The model’s nearness becomes a way to observe how color and pattern can share the same sentence without crowding. In this interior Matisse articulates a civilization of attention—one in which comfort and clarity are not opposites but partners. The painting is not a story about a woman; it is a structure that allows the ordinariness of a good room and the dignity of repose to be felt with precision.