Image source: wikiart.org

A Threshold Between Interior and Sea

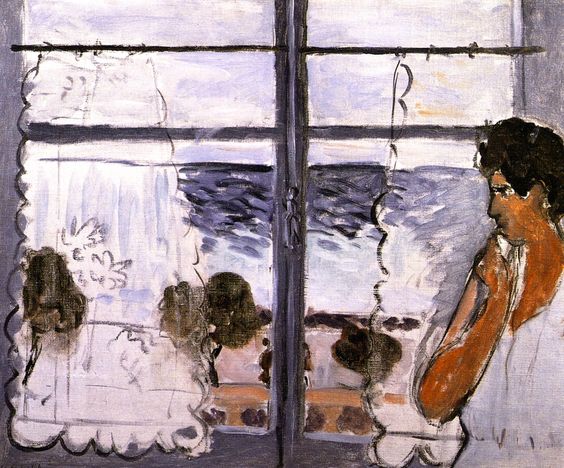

Henri Matisse’s “Woman at the Window” (1920) stages a meeting of two worlds separated—and joined—by a pane of glass. On the right, a young woman stands near a casement, head inclined and hand raised to her cheek as though caught between thought and attention. Before her, a wide window divides the canvas into four rectangles, the mullions forming a dark cross that anchors the composition. Outside, bands of sea and sky stack in soft, cool tones; inside, a pair of scalloped lace curtains frame the view with wavering edges and floral motifs. The subject is simple, almost minimal, yet the painting feels full: of air, of weather, of the quiet tension that lives at thresholds. Matisse uses spare means—few colors, clear structure, loose brush—to build an atmosphere in which seeing itself becomes the central drama.

A 1920 Language of Calm after Upheaval

Painted at the start of the 1920s, the work belongs to the moment when Matisse turned from the blazing chroma and abrupt contrasts of his Fauvist years toward a lucid, measured idiom. The broader European “return to order” after World War I did not make him academic; it made him economical. He was refining a language in which proportion and clarity could carry emotion. “Woman at the Window” bears that poise: reduced palette, decisive scaffolding, and just enough description to make the scene breathe. The image reads instantly from across a room and rewards slow looking up close—two ambitions Matisse pursued relentlessly in the Nice period.

The Composition Drawn by a Cross

The window’s cross is the painting’s skeleton. Two strong, charcoal-dark lines divide the field into quarters, giving the picture its stable geometry. This grid steadies the looser elements: the scalloped curtains that flutter along either jamb, the broken horizon of the sea, and the soft silhouette of the woman. The cross is not centered mechanically; it sits slightly left of the canvas midpoint and a touch high, which keeps the composition from feeling static. That displacement opens a column of space at right for the figure, while the left panes widen to host the curtains and a hint of foliage outside. Matisse has long loved the play between rectilinear order and curving arabesque; here the window’s geometry becomes a frame against which the human presence and the lace’s wavering edges can register as living.

Curtains as a Language of Line

The lace curtains do crucial work. Their scalloped borders echo the sea’s wavelets and the woman’s hair, softening the strictness of the grid. Within the fabric, Matisse sketches floral motifs with a few quick undulations; the forms are not details but signals, convincing because their rhythm matches the overall tempo of the picture. Even the way the curtains hang—slightly gathered at the top, slipping irregularly down the panes—reinforces the sensation of air moving through the room. The painter keeps the whites translucent, allowing the gray of the glass and sky to seep through; the result is a compelling illusion of gauze without literalism. As so often in Matisse, pattern isn’t ornament; it’s structure that breathes.

Palette and Light: Lavender Air and Mineral Blues

The color is subdued and exact. The sea and sky are built from mineral blues, steel grays, and lavender tints, brushed in long horizontal strokes that compress weather into quiet bands. Against this cool field, the interior whites of curtain and wall glow with a milky light. The woman’s skin carries low, warm notes—peach and umber—held in check so as not to disrupt the overall key. Her garment or towel takes on a faint orange-pink that places her gently forward without shouting. There are no saturated accents and no theatrical shadows. Illumination seems to arrive from the left—enough to halo the curtains and graze the figure’s cheek—but it is diffused, as if reflected off water. The painting is suffused with breathable light, the kind that offers clarity rather than drama.

Gesture and Psychology at the Edge of the Frame

The figure is rendered with striking economy. A few decisive strokes build the head and hair; a thin contour defines shoulder and arm; a compressed cluster of warm notes shapes cheek, nose, and mouth. The pose matters more than facial detail. Her hand to the face—half thoughtful, half shielding—conveys a listening posture: attentive to the outside yet aware of the inside. She is present but not posed. Matisse often avoids explicit psychology, trusting the arrangement of forms to carry mood. Here the mood is contemplative, even a little suspended, like the moment when you pause before a window to gauge the day.

Space Flattened and Felt

Space in “Woman at the Window” is shallow and convincing. The pane is close; the mullions sit almost on the picture plane; and the exterior layers of terrace, foliage, sea, and sky compress into stacked bands. Yet the scene never collapses into pure flatness. Overlaps (curtain before glass, figure before wall) and temperature shifts (cool out there, slightly warmer in here) supply depth. The viewer experiences the window as a barrier and a conduit at once: a surface that declares itself and a portal that delivers air and distance. This double role is the secret engine of the painting.

The Window Motif in Matisse’s Oeuvre

Windows run like a spine through Matisse’s career—from the exuberant “Open Window, Collioure” (1905) to the near-abstract “French Window at Collioure” (1914) and the many Nice interiors of the 1920s. They let him explore the central paradox of painting: a canvas is both a flat object and a view. In “Woman at the Window,” the motif becomes almost a meditation on this duality. The dark cross recalls the 1914 window’s structural severity, while the curtains recall the rhythmic patterning of his textile-rich interiors. Between them, Matisse locates a balanced register: neither purely decorative nor purely architectural, but a place where a human presence and a measured world meet.

Drawing That Happens Inside the Paint

Look closely and you can reconstruct Matisse’s method. He seems to have placed the grid early: long dark pulls for the muntins, a small knot for the latch. Over that scaffolding he scrubbed thin layers of gray-violet sky and blue sea, letting the bristle tracks remain visible so the surface feels aerated. He then laid the curtains with milky strokes, thin enough that the earlier tones breathe through. The figure’s head and arm were added with thicker, warmer brushwork, some edges sharpened, some allowed to dissolve into the light. There is almost no “finish” in the academic sense. Drawing is done by tone and pressure rather than by outline; edges are “lost and found” so the picture stays alive.

Pattern, Nature, and the Human Hand

What the viewer registers, after a minute, is how three kinds of pattern converse. Outside, nature arranges itself in bands and irregular clumps (sea, sky, foliage). Inside, the handmade pattern of lace echoes leaves while acknowledging that it is fabric—a human version of nature’s forms. Threading between them is the human figure, whose smooth skin and simple contour offer a third register of pattern: the body’s continuous edge. The painting’s calm harmony depends on the cooperation of these three: world, craft, and person.

Sound, Smell, and the Senses Beyond Sight

Although the image is quiet, it invites a synesthetic reading. The scalloped curtains suggest a faint rustle; the broken band of waves implies a muffled wash; the salt light against the panes seems to carry a clean smell. Matisse never paints these sensations directly. He implies them by leaving enough air in the color and enough softness in the touch for the viewer’s memory to step in. The very spareness of the scene allows other senses to join the eye.

The Ethics of Restraint

The painting’s strength lies in what it omits. There is no inventory of furniture, no intricate modeling of facial features, no descriptive detail in the terrace plants. By withholding, Matisse achieves dignity. The woman keeps her privacy; the sea keeps its distance; the lace keeps its suggestion. Exact relationships—between warm and cool, straight and curved, inside and out—do the expressive work. This restraint is not a stylistic gimmick; it is a moral stance that trusts viewers to meet the image halfway.

A Dialogue with the History of Window Pictures

From Renaissance Annunciations with parted curtains to Dutch genre scenes where women read letters by a casement, the window has long been a theater for inwardness meeting outwardness. Matisse keeps the tradition but changes its temperature. There is no anecdote to decode, no symbolic fruit on the sill. The exchange is purely perceptual: how a human body feels when placed beside a light source, how lace filters that light, how the sea’s horizontal insists on calm. In this reduction lies the work’s modernity. It treats the window not as a stage for story but as an instrument for seeing.

The Material Truth of Oil Paint

Oil paint is allowed to behave like itself. Thin passages reveal the weave of the canvas, especially in sky and curtain; thicker touches around the figure’s cheek and arm sit up slightly, catching the light like real skin. A few wet edges bleed into one another, creating the soft halation that makes the glass read as cool and the air as humid. Nothing is varnished flat. The viewer reads the picture in two registers at once: as a set of marks and as a world. That doubleness animates the experience long after recognition is complete.

How to Look Slowly

A good way to enter the painting is to begin, paradoxically, in the middle: rest your eyes on the tiny latch where the vertical and horizontal muntins meet. From there, move left through the gauze of the curtain and notice the floral loop that hangs like a low tide mark. Drop to the terrace band and sense its warmth under the cooler sea. Then climb back to the right-hand pane and let your gaze settle on the woman’s temple, where a single warm stroke turns the head. Finally, step back and let the grid and the scallops seal the composition again. Each circuit tightens the painting’s quiet spell.

Why the Image Endures

“Woman at the Window” endures because it clarifies a sensation most viewers recognize but rarely articulate: the small, charged pause when interior life meets exterior light. Matisse shows that you need very little to frame that experience—just a grid, a few curves, a handful of tuned colors, and a figure whose gesture lets the rest of the world in. The painting offers not spectacle but a stable place to breathe, an architecture of attention. Its freshness lies in the generosity of that offer.