Image source: wikiart.org

A Village of Boats Turned into Architecture

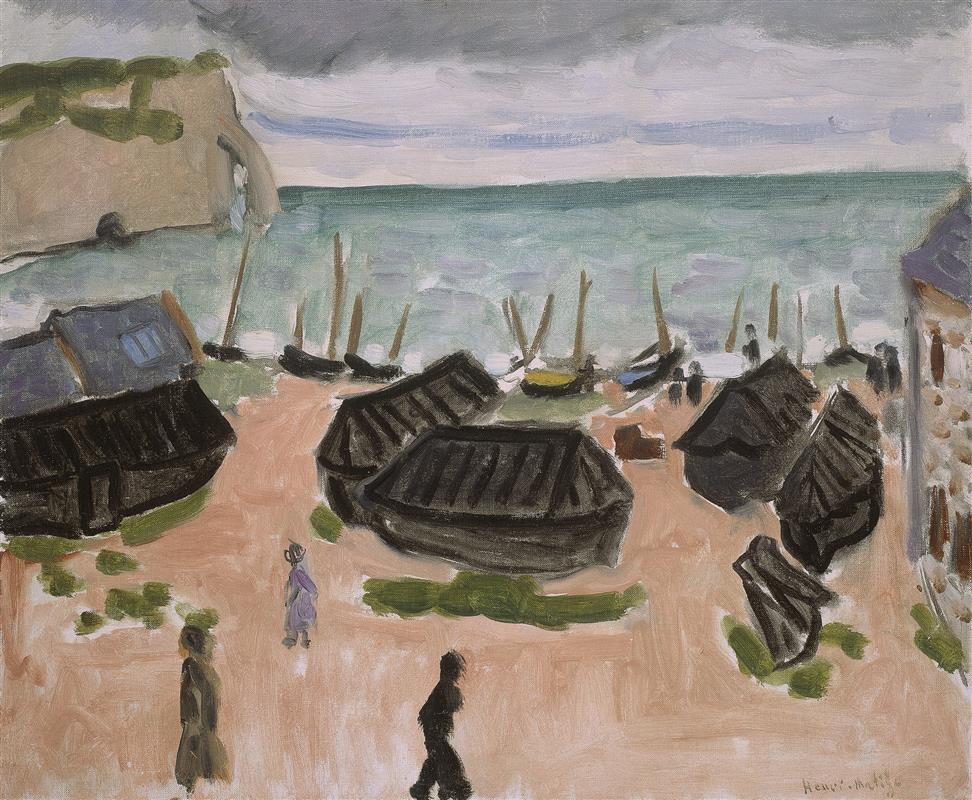

Henri Matisse’s “Les Caloges, Étretat” (1920) is a small coastal symphony composed from a handful of strong shapes and a disciplined, weather-toned palette. Across a sandy forecourt, dark pitched forms—some boats, some huts made from upturned hulls—sit in a loose circle like a village of wooden animals resting between tides. Beyond them, a thin green plane of sea glints under a low, slate sky; to the left the famous chalk cliff of Étretat rises, cool and massive; to the right a strip of stone wall closes the scene like a stage wing. Human figures appear as a few brisk notations—two walkers in the foreground, a woman in violet near the center, smaller silhouettes clustered at the waterline—so that daily life registers without distracting from the painting’s structural clarity. Matisse takes a working beach and turns it into an essay on weight, interval, and breath, using the local vernacular of “caloges” to anchor the composition’s rhythm.

What the Title Names: Caloges as Upturned Boats

In Normandy, “caloges” are old fishing boats that have been hauled ashore, upturned, and converted into sheds or huts. Tarred planks become roofs, ribs become walls, and the whole craft, retired from the sea, continues its service on land as storage for nets, lines, and tools. Matisse’s painting includes both these hut-like structures and ordinary boats pulled above the tide line. Their heavy, tar-dark hulls create a family of blunt, triangular masses set against pale sand and the milky Channel. Naming the caloges matters, because it clarifies why the beach feels lived-in even when the tide is out: the boats are not merely visiting; some have become houses. That shift from vessel to architecture gives the beach a domesticated gravity and supplies the painter with a ready stock of simplified, legible forms.

A Composition Built from Big Shapes and Clear Intervals

The composition is laid out on an open diagonal that runs from the bottom left corner toward the far right waterline. Matisse scatters the caloges along this diagonal in a pattern of advance and retreat: two large black hulls push forward near the center; smaller pitched forms step back to the right; low roofs hug the left edge; a wedge of figures and masts darts toward the water. The sandy ground opens into a broad central clearing, the lightest field in the painting, which acts as a stage for the few walking figures. This open zone is crucial. It keeps the many dark forms from coagulating into a single block and allows the eye to circulate. Behind this theater, the sea reads as a calm horizontal band, a tonal counterweight to the vertical thrusts of masts and cliff. The result is a design that holds together from across the room yet rewards close inspection with small asymmetries and local surprises.

Horizon, Cliff, and Sky: A Calm Architecture of Air

Matisse sets the horizon high, giving the foreground boats plenty of space to breathe. The band of sea is a steady green-gray plane, brushed in long horizontal pulls that flatten chop into a decorous shimmer. Above it, the sky occupies nearly half the canvas, worked in softly changing grays with a few paler seams, as if sheets of cloud were sliding across one another. This sky is not dramatic; it is a stable weight that helps articulate everything below. The chalk cliff at left cuts downward like a cool knife, its pale vertical an exact foil to the beach’s warm horizontal. The cliff’s top is capped with little caps of green, modeled by a few loose strokes—just enough to suggest vegetation without calling attention to itself. These large background elements—horizon, cliff, sky—form a steadied scaffolding, against which the irregular caloges feel both grounded and alive.

The Palette: Sand, Sea, Tar, and Weather

The color scheme is as frank as the place: sandy ochres and pinks for the beach; a mineral green for the Channel; tar-black mixed with earthy browns for the huts and hulls; olive patches of grass; and a range of cloud grays veering from cool violet to warm slate. Matisse allows a few small accents to punctuate this coastal key: a violet dress near the center, a yellow boat among the dark skiffs, and a blue rectangle of skylight on a roof to the left. None of these notes are loud; they exist to check monotony and to mark the painting’s rhythm. The restraint of the palette is deliberate. It preserves the feel of an overcast day and lets drawing and placement do the expressive work.

Brushwork That Names Materials Without Fuss

With a handful of moves Matisse declares what everything is made of. On the sea, long, even strokes give the surface its planar dignity. On the sand, broader, drier sweeps leave the weave of the canvas visible, suggesting grit and compacted paths. The caloges are blocked in with thick, tarry swathes that sit up on the surface, their edges softened in places to register worn timbers and tarred seams. Grass appears as short olive dabs that intrude on the sand like islands. The figures are a combination of quick verticals and ovals: enough to read as people but never so elaborate that they disrupt the painting’s tempo. This distribution of touch—slow for sea and sky, rough for boats, brisk for walkers—keeps the work legible and tactile.

Drawing by Masses and Edges

Matisse’s drawing happens mostly through the meeting of masses. The caloges are heavy blocks whose identity depends on silhouette and on the few bevels he adds along their roofs. The beach is not bounded by line but by the way sand lightens against grass and deepens against hulls. Even the cliff is carved out by a single crisp edge against sky and the darker mouth of a sea-worn arch. Where the painter needs to insist, he does so with a dark stroke: a door on the shed at left, ribs on the central boats, a quick punctuation for a head. Elsewhere he relies on tonal adjacency to do the job. The method is economical and forgiving. It allows the painting to be read swiftly and then, as the eye slows, to deliver convincing detail without pedantry.

Space Measured by Steps, Not by Ruler

Linear perspective plays a modest role. Depth is built through scale shifts and rhythmic spacing: boats shrink as they approach the waterline; masts thin and multiply; figures close to us are larger and darker, while those near the surf break into pale flickers. The open triangle of pale sand at center invites the viewer to imagine walking into the scene, crossing between the hulks toward the tideline. Because space is measured by these intuitive cues rather than by strict geometry, the surface remains decorative, with every zone—foreground sand, middle boats, far sea—belonging to the same pictorial fabric. It is a modern space, breathable and clear without being diagrammed.

Work, Weather, and the Rhythm of Daily Life

Although there is no overt narrative, the painting carries the murmur of labor and routine. The caloges testify to a decades-long practice of repair and reuse; the skiffs face the water with masts upright, ready for the next favorable tide; the people move about their business under a sky that promises neither storm nor sun. Matisse registers this social content by refusing melodrama. The small figures are not types—heroic fishermen, picturesque washerwomen—but anonymous townspeople who give the beach scale and pulse. In place of anecdote we receive a pattern of presence: boats, huts, walkers, sea, cliff; again and again, day after day.

The Postwar Return to Order, Lived on the Beach

Painted at the start of the 1920s, “Les Caloges, Étretat” belongs to the broader postwar “return to order,” a movement in which many European artists sought clarity, structure, and calm after years of upheaval. Matisse’s take on that return is not academic. He does not tighten contours into brittle correctness or extinguish the life of the brush. Instead he prunes everything to essentials: a tempered palette; an armature of big shapes; and a syntax of edges that carries the entire scene. The beach becomes the perfect laboratory for this experiment, because its vernacular forms—the almost abstract wedges of the caloges, the long strip of sea—already suggest a world of simplified geometry. The picture feels modern and classical at once: modern in its visible facture and frank abbreviations; classical in its balance and lack of strain.

Kinship with Matisse’s Other Étretat Views

Matisse painted Étretat more than once in 1920, shifting vantage points and degrees of crowding. Compared with his views that emphasize the grand arc of the shoreline or the sheer face of the cliff, “Les Caloges, Étretat” compresses attention into the working foreground. The sea is a band rather than a vista; the cliff a side character rather than a protagonist. This choice foregrounds mass and interval—the grammar he also used in his still lifes and figure interiors from the same year. The painting therefore reads as a coastal counterpart to his studio pictures: a stage set of functional objects arranged for maximum clarity and rhythm.

The Role of the Few Color Accents

The limited palette makes a few small accents do outsized work. The violet dress near the center quietly humanizes the composition and acts as a chromatic hinge between warm sand and cool sea. The single yellow hull among dark skiffs near the waterline inserts a sunlit echo in an otherwise overcast key, pulling the eye momentarily seaward. The little blue skylight on the left hut picks up the sea’s coolness and carries it into the foreground mass. These accents prove Matisse’s principle that one should change something only where the eye requires it; elsewhere, restraint preserves unity.

The Ethics of Exactness Without Pedantry

What holds the painting together is an ethic of exact relationships rather than of elaborated details. The size and spacing of the caloges are tuned so that they neither block the view nor disperse into noise. The horizon sits at the right height to stabilize the scene. The edge of the cliff cuts precisely where it will counter the flotilla of masts. Nothing feels accidental, yet nothing feels stiff. Matisse achieves that rare balance in which decisions are evident but not showy. The painting’s authority comes from this quiet exactness.

How to Look Slowly

A satisfying way to inhabit the painting is to take the route the composition proposes. Start at the lower left, where the largest hut presses into the picture like a dark wedge; feel how its roofline tilts you inward. Step into the pale clearing and meet the small walkers—one dark, one olive, one violet. Cross to the central boats and trace the ribs that turn their hulls from flat silhouettes into volumes. Follow the line of masts up to the steady band of sea and then to the low sky. Let your gaze slide along the horizon to the chalk cliff at left; drop back to the rocky arch; return diagonally across the beach, noticing how green patches interrupt the sand like syncopations. Each circuit slows the eye and clarifies how the painting breathes.

Material Presence and the Truth of Oil

The picture works because the oil paint remains present as material. Thin passages show the weave of canvas; thicker marks sit up like tar on wood; wet edges blur just enough to suggest damp air. Matisse does not smooth this variety away. He trusts that a viewer will accept the dual reality of paint and world, and that the friction between the two will yield pleasure. A beached boat is also a rectangle of dragged black; a figure is also a flick of bristles; a sky is also a field of layered grays. The painting invites you to shuttle between these readings at will.

Why the Image Endures

“Les Caloges, Étretat” feels fresh because it captures the essence of a specific place while demonstrating a timeless method of pictorial thought. It is local and universal at once: you can smell tar and wet hemp, yet you can also read the beach as a stable geometry of dark and light. The absence of spectacle gives it longevity. Nothing depends on novelty; everything depends on proportion, touch, and the patience of looking. A century later the beach still works, the boats still rest, the tide still waits, and Matisse’s marks still organize that quiet into a complete experience.