Image source: wikiart.org

A Room Redrawn by Gesture

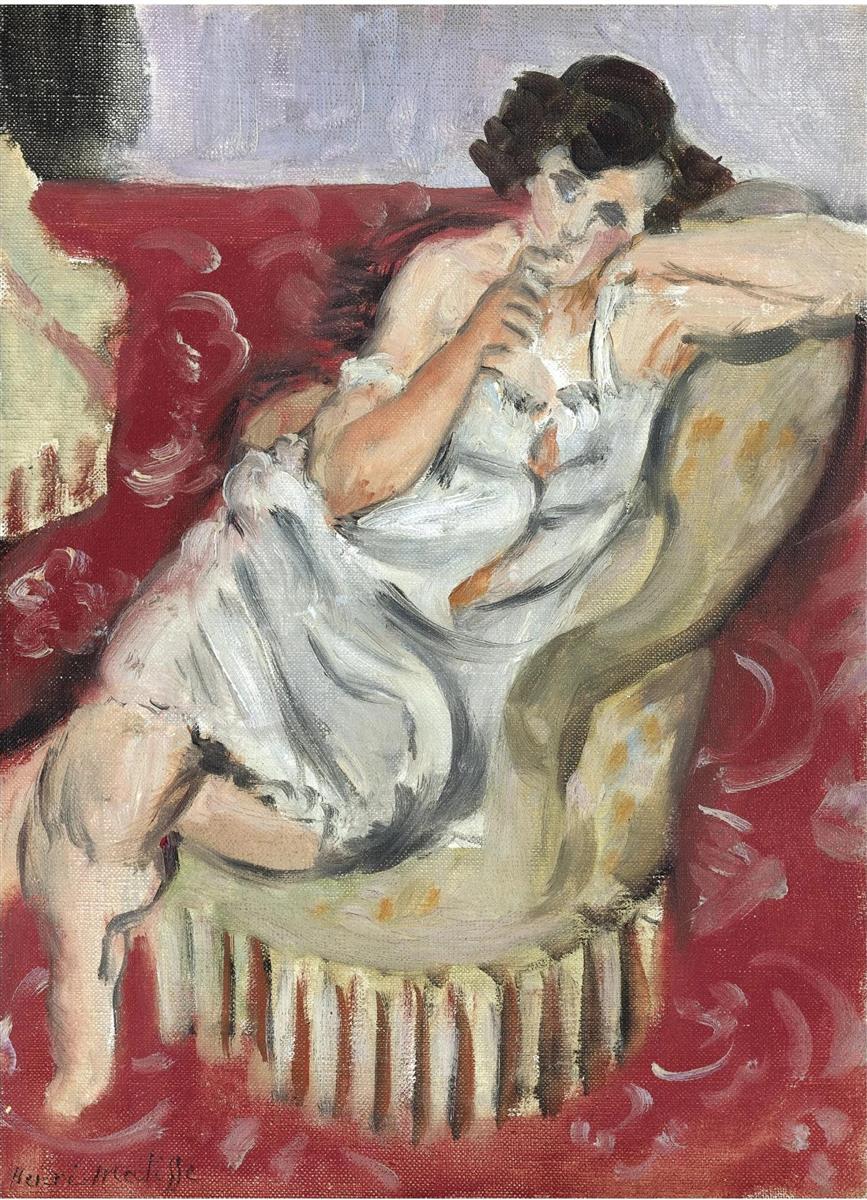

Henri Matisse’s “Nude in the Armchair” (1920) presents an interior transformed by touch. A woman reclines in a low, skirted armchair, her white chemise slipping to reveal the curve of her chest, while a red patterned ground presses forward like a tide of color. The subject is intimate and domestic, but the interest of the painting lies less in anecdote than in how Matisse constructs a world with a handful of decisive moves. Broad, creamy strokes build the body; fast, looping marks score the upholstery; a single lavender wall cools the heat of the room. It is a lesson in how a figure can feel alive when drawing happens inside the paint rather than on top of it.

A 1920 Pivot Toward Poise

Created at the opening of the 1920s, the picture belongs to Matisse’s early Nice period, when he tempered the volcanic color of Fauvism with a new attention to structure and atmosphere. The broader European “return to order” after World War I prompted many artists to revisit clarity, proportion, and calm. For Matisse this did not mean renouncing sensuality. Instead, he sought a poise in which drawing by masses, lucid color chords, and economy of detail could carry more weight than optical shock. “Nude in the Armchair” epitomizes that balance: assertive in touch, classical in construction, intimate in scale.

The Pose: A Spiral Held in Place

The model curves through the chair in a loose spiral that begins at the left knee, sweeps across the hips, rises through the torso, and comes to rest at the fingertip pressed lightly to the lips. Her other arm drops along the chair’s rim, closing the loop. This continuous line—what Matisse often called the “arabesque”—organizes the composition, making the figure feel both relaxed and cinched by an invisible rhythm. The head tilts forward in a thinking gesture; the body leans back; the diagonal of the chair’s arm counters the diagonals of torso and thigh. Everything locks into a dynamic repose.

The Armchair as Partner

Matisse stages the model not on a neutral ground but in a chair with real presence. The chair’s skirt is painted as a row of thick, vertical strokes that drum around the base, giving weight and anchoring the figure to the floor. Its side swells in a greenish envelope around the body, then collapses in deep shadow where the back meets the red divan behind. The chair is not merely furniture; it is a shape that answers the model’s contours, providing soft resistance. The tension between the chair’s swelling curves and the figure’s flowing arabesque sharpens the sense of contact.

Pattern as Space

The red ground is full of quick, semi-circular marks that suggest a patterned textile without literalizing it. These arabesques echo the curves of the figure and prevent the red from reading as a flat poster color. More importantly, they act as a shallow space-maker. Because the marks grow softer and darker near the seam where cushion meets wall, they help register depth without resorting to heavy modeling. The pattern thus performs double duty: decorative and structural.

Color Chords: Red, White, Olive, and Violet

The palette is intentionally limited and finely tuned. Red dominates, but it is not a single red. Matisse varies it from wine to vermilion to dusky carmine, letting thin passages vibrate against thicker ones. Against this field, the figure’s white chemise is not pure white but a medley of cool grays and warm creams, with flicks of chalky impasto to catch the light. The chair’s olive tones carry just enough yellow to feel sun-touched, while the wall’s pale violet calms the composition like a breath of cooler air. Small oranges and pinks at elbows, cheek, and breast lift the flesh without over-modeling. Each color has a task and does it without waste.

Flesh Without Fuss

The body is constructed with remarkably few marks. Broad wet strokes turn at the shoulder to create the roundness of an upper arm; a long, loaded stroke defines the thigh and then breaks at the knee; a darker drag underneath cinches the volume. The breasts are indicated by pressure changes and warm notes rather than descriptive outlines. This economy produces an unusual effect: the figure feels solid and vulnerable at once, fully present yet never labored. The viewer senses the painter thinking with the brush, choosing exactly how much to say and no more.

Drawing Inside the Paint

A hallmark of the work is how drawing happens through the modulation of tone and the speed of the brush. Instead of enclosing forms with tight lines, Matisse lets edges form where a cool gray meets a warm beige, where a swept midtone collapses into shadow, where a hairline of dark accent clarifies a fold. The line that does appear—the contour of a calf, the arc beneath a breast—arrives like a concluding sentence, not a beginning. This approach keeps the surface alive and prevents the image from feeling diagrammed.

The Face as a Quiet Center

The head is small relative to the body, and its features are summarized: a cool violet for the shadowed eye socket, a quick red note at the nose, a warm angle for the mouth barely visible behind two fingers. Yet the face exerts a calm gravity that gathers the surrounding action. The tilted brow and the hand-to-lips gesture suggest reflection or fatigue rather than theatrical seduction. In many Nice interiors Matisse uses psychological neutrality to let color and placement do the expressive work. Here the effect is intimate and humane. The model is a presence rather than a type.

Light and Air in an Indoor Scene

Although this is an interior, Matisse paints as if the air moves. Light slips in from the left, hitting shoulder and knee, but never crystallizes into hard shadow. The chemise catches that light in ridges and ridgeless smears, while the chair absorbs it, turning olive to ochre on raised planes. The overall tonality is warm, but the lavender wall and cool grays running through the whites keep heat from overwhelming the picture. The color of air is as important as the color of objects; it threads the scene with coherence.

Cropping and Proximity

The figure is cropped at the ankle and shoulder, an intimate framing that intensifies the sense of nearness. The viewer seems to stand at the limit of the chair’s skirt, just inside the model’s space. Cropping also energizes the composition by eliminating the option of escape; there is no empty neutral zone to rest the eye. Instead, the viewer rests inside the colored envelope of the room, where everything touches or nearly touches something else.

The Tempo of the Brush

Speed varies across the surface. The patterned red is laid in with fast, looping wrist movements; the chemise involves longer, more elastic pulls; the chair’s base is built from brief, percussive downward taps. Matisse orchestrates these tempos so the painting reads as a single experience rather than a catalog of parts. You feel a slow chord under the figure and quick decorative trills around her, with a steady medium tempo in the flesh. This musical analogy is more than poetic; it captures how Matisse distributes energy across the canvas to keep the viewer’s attention moving.

From Ingres to Nice: A Modern Odalisque

Matisse’s interest in the reclining female figure has roots in the odalisque tradition of Ingres and the nineteenth century. But where Ingres polished surfaces into idealized marble and multiplied fabrics, Matisse distills. He keeps the basic schema—a woman at ease in a patterned interior—while stripping away finish and allegory. The result is modern not because it rejects the past but because it transforms past language into a tool for immediacy. The model is not a fantasy concubine; she is a contemporary woman absorbed in her own thoughts within a room made vivid by paint.

The Ethics of Simplification

Simplification in this painting is not shorthand or laziness. It is a way of letting relationships carry meaning. The pale chemise is only as light as it needs to be to float against red; the chair is only as modeled as necessary to hold the body; the face is only as described as required to center the pose. This restraint asks viewers to finish the image with their perception. Matisse leaves space for the mind to complete what the brush implies, trusting that the essentials—curve, weight, warmth—are enough to spark recognition and sympathy.

Tactile Reality and the Material of Oil

The physical character of oil paint plays a starring role. Thick strokes stand as ridges on the chemise; thin washes leave the weave visible along the red ground; wet-in-wet passages let colors braid at the edges so that a shadow never becomes a dead zone. Because the paint’s materiality is evident, the scene never drifts into illustration. It remains a painted fact, and the viewer’s awareness of that fact intensifies the encounter with the body and the chair. The painting asks to be seen and felt, not merely decoded.

Space Without Perspective Tricks

Depth in the image is built by overlap and temperature, not by linear perspective or detailed floor planes. The chair overlaps the red divan; the figure overlaps the chair; a cool wall retreats behind the warmth of both. Small dark accents at the back of the chair and in the crook of the elbow deepen local pockets without breaking the overall shallow stage. The room is close, comfortable, and breathable. Its stage-like shallowness pulls pattern, furniture, and body into the same register, reinforcing the sense that everything in the room belongs to the same pictorial fabric.

Emotion in the Gesture, Not the Face

Because the facial description is spare, emotive content migrates into pose and paint handling. The relaxed hand falling along the chair reads as release; the other hand near the mouth reads as thinking or withholding. The chemise’s loose folds, animated by large strokes, feel like the residue of movement, as if the figure has just settled. Even the visible fringe of the chair’s skirt, with its friendly, repetitive rhythm, contributes to the painting’s mood of informal privacy. The picture is sensual not through display but through the truthful registration of weight and rest.

Relationship to the Nice Interiors

“Nude in the Armchair” sits comfortably among the Nice interiors that occupied Matisse through the 1920s, where models appear amid screens, carpets, and draperies, all rendered with clarity and a love of pattern. Here the vocabulary is reduced to essentials: a single chair, a single textile, a single wall tone. That reduction magnifies the figure’s presence and lets the painting demonstrate Matisse’s core method without ornament. It is as if a larger interior has been compressed to the scale of a conversation between body and chair.

How to Look Slowly

A satisfying way to view the painting begins with the large relationships—red versus white, curve versus angle—then moves to the hinges that hold the composition: the dark seam where the chair’s back meets the cushion, the sharp notch of shadow at the armpit, the small warm strike that turns the cheek. Return finally to the base fringe and follow it around the circumference; feel how its rhythm measures the figure’s weight. This movement from field to detail to field mirrors the painter’s own oscillation between overview and touch.

Why the Image Endures

The picture’s longevity stems from its clarity and generosity. It offers an immediately legible scene—a woman at ease—while rewarding close attention with countless small decisions that keep the surface alive. It reframes an age-old subject through modern means: simplified color chords, drawing by masses, and a faith that tactile paint can hold emotion without narrative crutches. Above all, it preserves the dignity of the model’s presence. She is not an emblem or a spectacle; she is a person resting in a room, given to us with honesty and care.