Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

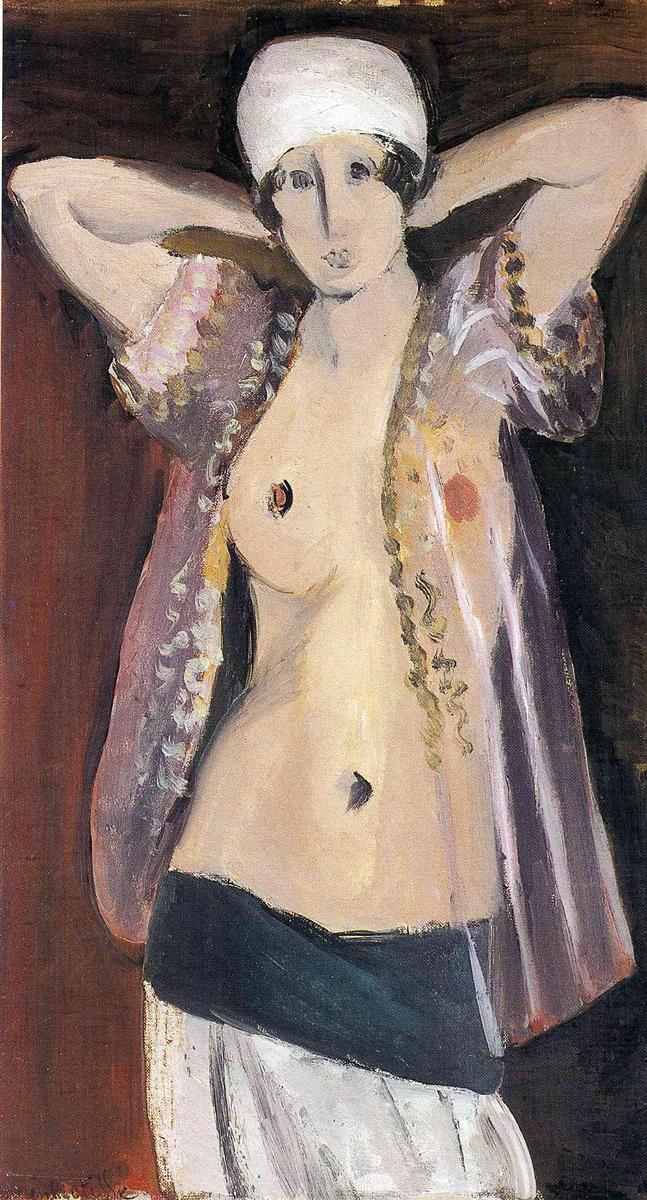

Henri Matisse’s “The Transparent Blouse” (1919) is a poised, vertical canvas in which a standing model arranges her arms behind her head and meets us with a calm, almost masklike face. She wears a white turban, a dark sash around the hips, and—true to the title—a diaphanous, mauve-rose robe that opens to reveal the torso. The background is a low, reddish umber that neither describes a specific room nor dissolves into abstraction; rather, it is a field against which the figure breathes. Painted during the first years of the Nice period, the work condenses Matisse’s search for equilibrium after the upheavals of the 1910s: modest palette, decisive contour, and an air of Mediterranean light held in reserve. The blouse is the painting’s technical subject, but the real theme is translucency—how paint can suggest air passing through fabric, how a body can be outlined without being pinned down, and how intimacy can be created through restraint.

The Nice Period and a Return to Light

By 1919 Matisse was spending long stretches in Nice, working in rented hotel rooms and apartments whose screened windows, patterned draperies, and sun-washed walls became a vocabulary. In contrast to the chromatic extremity of Fauvism and the structural puzzles of the pre-war decade, these interiors aim for clarity, warmth, and a living, everyday elegance. “The Transparent Blouse” distills that aim. Instead of crowding the picture with mirrors, shutters, or patterned carpets, Matisse gives us a single figure and a background that suggests depth with the faintest tonal shifts. The simplicity is not a retreat; it is a deliberate clearing of space so that the nuances of color temperature, the life of the contour, and the vibration between opacity and transparency can be felt.

The Posed Body and Modern Poise

The model stands with feet and hips aligned to the picture plane, torso subtly twisting as the arms rise behind the head. This arm position opens the chest without bravado and creates two long diagonals that counter the canvas’s strong vertical. The pose reads as confident rather than coy. There is no mythological cover story—no nymph or Venus, no allegorical attribute—only a contemporary woman in a studio, wearing a turban and a robe that belongs to the theater of Nice as much as to any harem fantasy. Her expression is economical, built from a few firm marks for eyes and mouth; Matisse’s portraits from these years reject melodrama in favor of presence.

Composition and the Architecture of Curves

Compositionally, the figure is a column set just off center. The narrow format heightens the sensation of lift produced by the raised arms, and the cropped lower edge focuses attention on the torso and blouse. Curves structure the painting: the arc of the turban, the soft loop of shoulders, the semicircle of the breasts, the scalloped edge of the robe, and the gentle S-curve from throat to navel. These curves are orchestrated against quieter verticals—the line of the sternum, the fall of the robe, the side edges of the canvas—so that the image breathes but never sags. The negative spaces under the lifted arms create two almond-shaped apertures that allow the warm ground to show through, making the body feel set forward without using heavy shadow.

Color, Temperature, and Limited Means

Matisse holds the palette to a few notes: the luminous flesh constructed from yellow ochre, white, and a touch of rose; the mauve and smoky lilac of the sheer robe; the near-black sash cooling the hips; the white turban and skirt; and the reddish-brown ground. Because there are so few colors, each relation matters. The mauves are cool in hue but warm in handling, their edges brushed thin so the underlying ground peeks through and warms them. The sash, a deep blue-black, is the painting’s only low value mass; it anchors the figure and prevents the torso from feeling disembodied. The turban’s clear white, echoed in the skirt and in small breathing strokes along the robe’s trim, provides the high note that keeps the picture’s key fresh.

The Transparent Blouse as a Painting Problem

The title announces a challenge: to conjure transparency in an opaque medium. Matisse’s solution is not to paint glassy illusion but to stack veils. The robe is laid in with thinned paint scumbled over the ground so that pockets of umber glow through, very much as a thin fabric reveals the warmth of skin beneath. Where the robe crosses the darker zone near the arm, the color deepens; where it arcs over lighter flesh, it turns pearly. The trim of the robe—suggested by a chain of quick, warm strokes—registers as embroidery without ever being counted stitch by stitch. Transparency here is the coordination of three facts: a visible weave of canvas, a film of color laid lightly enough to admit light, and a sensitive calibration of whatever lies “behind” the fabric.

Drawing with a Living Contour

Line carries as much meaning as color. Matisse’s contour is a brush line that thickens at turning points and thins where planes meet gradually. The breast, for example, is caught by a short, weighted hook of line; the flank is a long, slower stroke; the navel is a single small comma. Around the turban and hair, the line is more definite, anchoring the head so the shoulders and robe can remain airy. These lines are not barriers around shapes but traces of movement, the record of a hand deciding where pressure belongs. The figure’s vitality comes from the way contour and color continually trade responsibility for describing form.

Light Without Spectacle

The light feels Mediterranean but tempered, as if filtered through shutters. There is no theatrical spotlight and no single dramatic cast shadow; instead, value sits largely in a mid-range, letting temperature shifts do most of the modeling. The chest turns with a hinge of cooler tone; the abdomen brightens subtly; the face holds a flatter value so the large planes read at once. Highlights are few and carefully placed: a whisper across the turban, glints along the robe’s sleeve and trim, a note at the shoulder. The economy of these accents keeps the surface unified and resists the literalism that would break the picture into glossy fragments.

Surface, Facture, and the Breath of the Ground

Much of the appeal of “The Transparent Blouse” lies in Matisse’s handling. The ground—warm, absorbent, and visible— participates in almost every passage. Flesh is often a single wash over that ground, with a cooler pass of semi-opaque paint to turn form and a darker stroke to confirm the contour. The robe is painted wet into dry, so small broken edges show, like frayed threads catching the light. The sash is more opaque, its confident sweep reminding us that firmness can be achieved with a single loaded stroke. Nowhere does the surface close down into a polished skin; one always senses air trapped between layers.

The Turban and the Language of Costumes

The white turban serves both pictorial and cultural roles. Formally, it provides a clear oval counterweight to the dark sash and frames the face against the warm ground. Historically, it nods to the Orientalist costumes Matisse explored repeatedly in Nice: sashes, caftans, scarves, and robes that allowed him to study color and pattern independent of Western dress conventions. In this painting the turban’s whiteness, not its exoticism, matters most. It lifts the upper register of the picture and makes the head a cool lamp above the warmer body.

Sensuality Through Restraint

The painting is undeniably sensual, yet it avoids sensationalism. The nipples are marked with quick, circular notes; the navel is a small crescent; the pubic area is veiled by the sash and skirt. Matisse offers just enough information to let the viewer feel the weight and softness of flesh. The real seduction lies in the transitions: skin meeting sheer fabric, cool lilac meeting warm ochre, firm contour relaxing into a wash. The raised arms open the chest, but the expression remains reserved. This union of invitation and reticence is central to Matisse’s modernism, which seeks pleasure without aggression.

Space, Depth, and the Refusal of Illusionism

Although the background carries tonal shifts, it remains fundamentally planar. Depth is asserted by the overlap of sleeves against ground and the forward push of the torso, not by perspectival lines or cast shadows. The figure inhabits a shallow, stage-like zone—enough space to breathe, not enough to engross us in anecdote. This refusal of full illusion keeps the painting contemporary; the image acknowledges its own construction even as it persuades.

Relation to Other 1919 Nudes

Placed beside the reclining nudes and Spanish-carpet interiors of the same year, “The Transparent Blouse” reads as a vertical counterpart: fewer props, more air, a tighter focus on the dialogue between body and cloth. In the reclining works the surrounding pattern is a co-equal protagonist; here the garment bears that responsibility. Across the year, Matisse tested how little or how much decor a figure needs to feel at home. This painting sits near the minimal end of that spectrum, relying on transparency, posture, and contour for its drama.

Materials and Palette Inference

The harmony suggests a concise box of pigments. Lead white provides luminosity; yellow ochre and raw sienna supply flesh warmth; vermilion or red lake tips the nipples and lips; ultramarine or cobalt, nudged by a little black, cools the shadows and builds the mauves; ivory black deepens the sash and draws the firmest contours. Medium is sparing; much of the paint is thinned with solvent to create those breathable washes. This limited set allows subtle temperature games without the confusion of too many hues.

Rhythm and the Eye’s Journey

The painting rewards slow circling. Many viewers begin at the white turban, descend the clean line of nose and philtrum to the small mouth, and then move outward along the oval of the face to the curve of shoulder. From there the eye glides over the scalloped trim, crosses the torso via the diagonal band of light at the abdomen, catches on the dark sash, and finally returns upward through the left sleeve to the turban again. Each circuit rehearses the essential oppositions: cool to warm, opaque to sheer, curve to column. Because the edges remain soft and the palette disciplined, this movement feels continuous rather than jumpy.

Modern Presence and the Question of the Gaze

The model’s gaze is level, neither imploring nor evasive. She is neither classical ideal nor private fantasy; she occupies the painting with contemporary autonomy. That autonomy derives partly from Matisse’s refusal to fix the face into a specific narrative. The features are simplified, as if he wanted the viewer to register “a person” before attempting to read “this person.” The effect is to relocate interest in the painterly encounter itself: a living body, a living line, a living fabric of paint.

What the Painting Teaches About Looking

“The Transparent Blouse” suggests a method for seeing: attend to the relations, not the labels. If you follow the tiny coolings along one breast and the corresponding warmings at the other; if you notice how the robe darkens where arm and torso overlap, or how the sash’s single stroke pulls the composition taut; if you let the negative spaces under the arms rest on your retina—you begin to feel that perception is itself a form of composure. In that composure lies the picture’s lasting pleasure.

Conclusion

With deceptively few means—muted color, living contour, and luminous thin paint—Henri Matisse makes transparency the engine of form. The blouse is both garment and metaphor: a skin of paint through which another skin glows. The turban cools the head; the sash anchors the hips; the reddish ground cradles everything in warm air. Nothing is insisted upon and nothing is left vague. The result is a modern nude that takes its power not from spectacle but from the accuracy of sensation. “The Transparent Blouse” belongs to that small class of pictures that seem to breathe; they do so because the artist trusted paint to do exactly what fabric does—filter light, carry color, and reveal the body beneath without giving it away.