Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

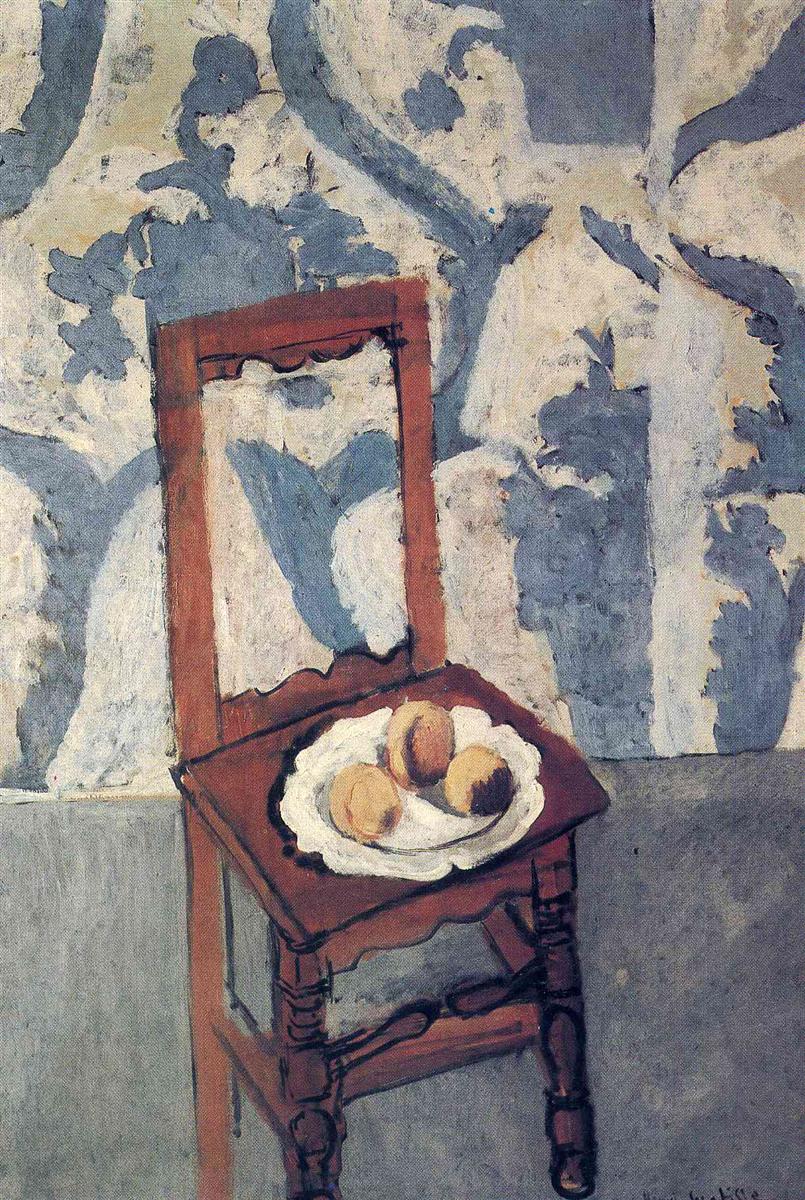

Henri Matisse’s “The Lorrain Chair” (1919) turns a modest corner of a room into a taut meditation on balance, rhythm, and domestic presence. A simple wooden chair—angular, provincial, and slightly askew—supports a white dish bearing three golden fruits. Behind it, a wall of blue-gray and chalky white arabesques sways like fabric caught by light. The floor is a quiet slab of gray. Nothing more happens, and yet the picture pulses with attention. Matisse uses pared-down means—firm contour, economical color, and a deliberate play between geometry and ornament—to show how an ordinary object, properly seen, can carry the full weight of painting.

The Nice Period and a New Calm

Painted during Matisse’s first years in Nice, “The Lorrain Chair” belongs to a body of work defined by interior subjects, softened light, and a controlled palette. After the intensity of Fauvism and the structural experiments of the 1910s, his Nice canvases cultivate clarity and repose. Windows, shutters, mirrors, table tops, flowers, chairs, and textiles become instruments for measuring light and arranging color relations. This still life exemplifies that aim. The picture’s calm is not emptiness; it is the result of careful omission. By restricting the elements to chair, plate, fruit, wall, and floor, Matisse makes every relation count.

A Still Life Built from Planes

The composition is organized by two dominant planes: the vertical pattern of the wall and the horizontal plane of the floor. A crisp seam—set a little below mid-height—marks the meeting of these planes and lays down a stage on which the chair can act. Matisse places the chair slightly off-center and turns it on a diagonal, so the front legs project toward us while the back posts lean into the wall. That diagonal movement enlivens the otherwise planar setting. The backrest creates an inner rectangle—a picture within the picture—that traps a slice of the patterned wall and reinforces the painting’s theme of framing and enclosure.

The Chair as Motif and Character

The chair is no anonymous prop. Its scalloped aprons and turned stretchers hint at a vernacular French type often associated with eastern regions such as Lorraine (the title’s “Lorrain” points to that connection). Matisse picks out the chair’s structure with succinct, slightly elastic lines of dark paint. Contours thicken at joints and thin along straight runs, recording the pressure of the hand and the grain of wood. The warm, reddish-brown body of the chair sets it apart from the cool wall and floor, establishing a temperature contrast that makes the object feel present and touchable. By letting the backrest cut through the wallpaper’s motifs, he fuses object and setting without letting either dissolve.

Pattern, Ornament, and the Breath of the Wall

Matisse’s blue-gray wall is a theater of motifs. The arabesques echo vegetal forms—buds, leaves, fronds—recalled with broad, loaded strokes and scumbles of white that allow the linen texture to glint through. Rather than a literal wallpaper, the wall reads as an abstract field of pattern that vibrates between figure and ground. Importantly, the patterns do not obey the chair; they continue right through the inner rectangle of the backrest, as if the wall were breathing behind it. This refusal to “fill in” the backrest with a different tone keeps the surface continuous and affirms the painting’s allegiance to flatness even as it conjures space.

Fruit, Plate, and the Problem of Weight

On the seat rests a white, scalloped dish with three round fruits—likely lemons, given the Nice setting and their clear yellow hue. Matisse positions the plate not exactly centered but nudged toward the front edge, creating a delicate instability that the chair’s front rail promptly arrests. The plate’s crisp white establishes the highest value in the picture, and because it carries the painting’s brightest light, it becomes the visual fulcrum. Around it, the fruits’ ochres and citrons concentrate warmth. Their small shadows are soft and economical, sufficient to set them down on the plate without theatrical modeling. The effect is one of weight and levitation at once: the plate seems to sit firmly, yet the fruits hover on the cusp of rolling.

Drawing with a Living Line

The picture is sewn together by Matisse’s unmistakable line. He outlines the chair, dish, and the seam of the floor with a brush line that behaves like ink—supple, variable, and alive. Nowhere is it mechanical. At corners the line hesitates; at curves it accelerates. Around the dish and fruit, a discreet dark contour acts not as a cartoonish border but as a note of emphasis, an edge that focuses the eye. The wallpaper motifs are also drawn, yet with a wider, wetter touch. This contrast—taut line for object, broad sweep for background—lets the viewer feel two different energies in the same room: structure and ornament, carpentry and textile.

Color Architecture: Cool Ground, Warm Accent

“The Lorrain Chair” is a lesson in temperature control. The wall and floor are cool fields of grays and blue-grays, mixed from white, ultramarine, and muted earths. The chair and fruit provide warm counterweights—reds, siennas, and yellow ochres modulated with white. Because the warm notes are concentrated in small, clearly bounded shapes, they command attention without overwhelming the picture. The white of the plate, a different kind of brightness from the wall’s chalk, unifies warm and cool by touching both families: it carries a cool reflection from the wall’s blues and a warm tint from the fruit. Harmony arises from adjacency and restraint rather than from saturation.

Space Without Illusion

Depth is achieved by overlap, not by linear perspective. The chair’s feet rest on the floor plane, but Matisse refuses cast shadows that would lock the chair to a single light source. The back legs melt slightly into the gray and blue of the wall and floor, easing the chair into the space rather than pinning it there. Within the backrest, the captured wallpaper pattern reminds us that space continues behind the object, yet the unbroken surface of paint keeps us aware of the canvas. The result is a subtle, modern equilibrium between objecthood and flatness.

A Domestic Still Life with Human Echoes

Though no figure appears, the painting brims with human implication. The seat, turned slightly, feels as if someone has just risen and set down a plate of fruit. The height of the backrest relative to the picture plane is roughly head-height for a sitter; the inner rectangle could frame a face. Matisse often nested portraits within interiors and used empty chairs as stand-ins for human presence. Here the curved scallops of the chair echo a smile; the four legs mimic a stance. The domesticity is intimate but unsentimental; the room is lived in by the act of looking.

Rhythm: From Pattern to Plate to Floor

The viewer’s eye travels in loops. Many begin with the bright plate and fruit, climb the diagonal of the chair’s seat to the backrest’s inner frame, then slip into the wallpaper’s undulating pale forms. These forms in turn pour the eye down the seam where wall meets floor, returning it to the chair legs and across the front rail back to the plate. Each circuit rehearses the picture’s core oppositions: warm to cool, curve to angle, object to field. Because these contrasts are gentle rather than extreme, the painting sustains attention without spectacle.

Technique, Materials, and the Breath of the Ground

Matisse’s facture is deliberately visible. Broad areas of wall and floor are laid in with thin, semi-opaque strokes that let the ground breathe. You can feel the drag of a wide brush across the linen weave, the slight gaps where a lighter under-tone peeks through. The chair and plate are painted more opaquely, but even here he stops short of enamel-like finish; touches remain open at edges so that background and object communicate. The pigment set was likely compact: lead white, ivory black, ultramarine or cobalt blue, yellow ochre, raw sienna, and small additions of umber. This economy suits the painting’s ethic of clarity.

The Chair in Matisse’s Vocabulary

Chairs recur across Matisse’s Nice pictures as actors, pedestals, and compositional anchors. In some canvases they cradle models; in others they bear flowers or fruit. “The Lorrain Chair” is exceptional for allowing the chair to star by itself. The choice underscores Matisse’s confidence in the expressive potential of plain furniture. It also highlights his attraction to vernacular design: turned legs, scalloped aprons, and the faint irregularities of handmade woodwork harmonize with his hand-made line. The chair’s name points to a regional type, but Matisse absorbs the cultural reference into pure pictorial function.

Ornament Versus Geometry

One of the painting’s quiet dramas is the contest between the wall’s vegetal arabesques and the chair’s hard carpentry. The ornament wants to flow; the carpentry wants to right angles. Matisse mediates the contest with small, witty adjustments. The back rail’s scallop repeats the wall’s curves, while the linear rungs and legs stand firm against the wallpaper’s tide. Even the plate participates, its wavy rim echoing the wallpaper yet its circle asserting geometric calm. The picture thus becomes a negotiation between two ways of organizing experience—organic pattern and measured structure—resolved not by argument but by harmony.

Nice Light and the Key of the Picture

Although painted indoors, the canvas carries the key of Mediterranean daylight. Values gather in the middle range; extremes are few. The brightest whites belong to the dish and a few chalky wall passages; the deepest darks are the accents of contour, not broad shadows. This middle-key approach keeps the atmosphere airy and prevents heavy contrast from cutting the room into hard zones. It is a daylight painting, even without windows. The very choice of blue-gray, rather than brown or black, for the wall’s motif evokes the coolness of sea air.

From Everyday to Exemplary

Why should a wooden chair and a plate of fruit hold the eye so long? Matisse answers by uncovering order in the ordinary. The chair’s diagonals organize the rectangle of the canvas; the fruit’s clustered circles temper those diagonals; the wallpaper’s rolling motifs supply counter-rhythm. Each element helps the others be seen. The painting models a way of looking at daily life—attentive, patient, exact—until a fragment of a room becomes sufficient to describe a world.

Relation to Cézanne and the Modern Still Life

Matisse revered Cézanne, and this picture engages that lineage while maintaining his own voice. Like Cézanne, he builds space with color relations and stabilizes it with firm contour. But where Cézanne multiplies facets and weight, Matisse chooses economy and air. The plate does not tilt precariously; it rests. The wall is not an accumulation of small planes; it is an open field of gesture. The modernity here lies not in distortion but in the candor with which paint declares itself while still delivering the sensation of objects in space.

Looking Instructions: How the Painting Opens

Stand close enough to sense the weave of the canvas in the wall’s white scumbles, then back away to let the wallpaper pattern condense into a soft, leafy haze. Notice how the chair’s contour darkens slightly where it meets the light wall, then lightens where it runs along the warm seat, as if contour and color were negotiating ownership of the edge. Watch how the inner rectangle of the backrest resists becoming a hole; it is simply more of the wall. Linger on the fruits’ shadows—so little, yet sufficient. The more you circulate through these small observations, the larger the room within the painting becomes.

Enduring Significance

“The Lorrain Chair” endures because it demonstrates Matisse’s central conviction: painting can transform the familiar not by exaggeration but by exactness. The chair is a chair, the fruit are fruit; yet the relations among them—angle to curve, warm to cool, object to field—are tuned with such poise that the scene becomes exemplary. In 1919, as he recalibrated his art toward clarity, Matisse found in such humble interiors a path to permanence. The painting asks nothing more of the viewer than unhurried looking, and in exchange it offers a fully formed world assembled from wood, plaster, linen, pigment, and light.