Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

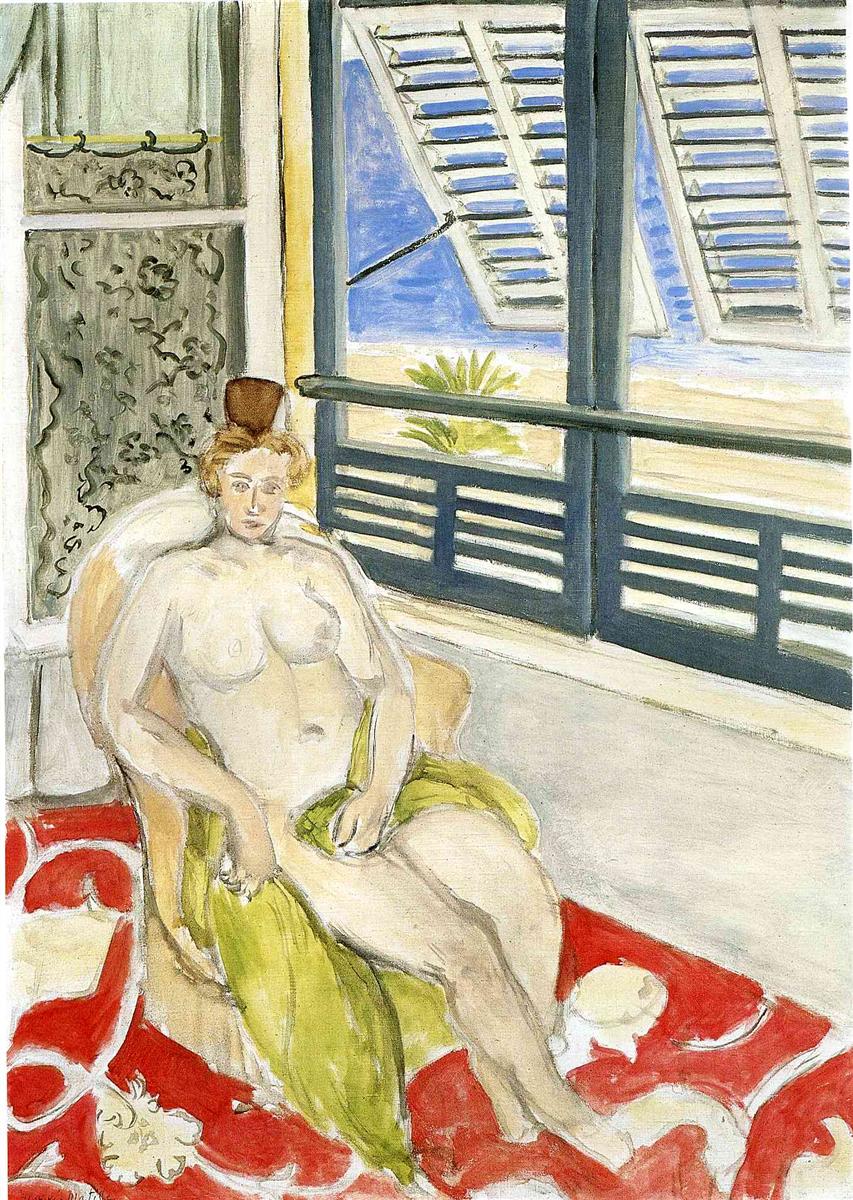

Henri Matisse’s “Nude” (1919) is a poised interior from the artist’s early Nice period, where he reimagined the classical subject of the seated nude through the cool, luminous light of the Mediterranean. A woman sits upright in an armchair near a wall of louvered shutters; beyond them, a strip of beach, sea, and a palm are glimpsed in the glare. Inside, a red carpet with scrolling, ivory arabesques unfurls beneath her feet, and a green drape gathers across her lap like a second skin. The image is simultaneously intimate and architectural. Matisse does not stage an anecdote: he composes a chord of color—sea blues, coral reds, leaf greens, and milk-white flesh—so precisely tuned that the room itself seems to breathe.

The Nice Period and the Return to Clarity

Painted just after World War I, “Nude” belongs to a decisive chapter in Matisse’s career. In Nice he turned from the combustions of Fauvism and the structural experiments of the 1910s toward a calmer lyricism. Light became a subject in itself; interiors, shutters, patterned carpets, and quiet figures were used like instruments to measure and hold that light. Rather than shouting with saturated primaries, he calibrated temperature and value to make spaces that feel habitable and durable. This canvas exemplifies that aim: the figure is simplified, the drawing sure and elastic, the palette compressed but radiant. It is not a retreat from modernity but a modern clarity—an art of steadiness after years of upheaval.

First Impressions and Motif

The scene appears simple yet carefully staged. A nude woman sits forward on an upholstered armchair, one hand resting on her thigh as the other gathers a leaf-green drape. Her hair is coiled high and her gaze meets ours directly—frank, untheatrical. To her right a window wall fills almost half the picture, its shutters tilted outward to vent the Riviera sun. Through the slats we see the beach’s pale band, a cobalt sea, a fringe of sky, and the dark fan of a palm. The lower field is bounded by a red carpet patterned with swirling ivory forms that echo the Mediterranean arabesque. Matisse condenses figure, textiles, and architecture into a single, legible chord.

Composition as Architecture

The composition is governed by the grid of the window and by the triangular mass of the figure. Three vertical mullions stabilize the right half; a stout horizontal rail pins them together like the crossbar of a musical staff. The diagonal of the raised shutter injects motion and leads the eye outward to sea. The body, by contrast, builds a compact triangle rooted in the chair and rising to the coil of hair—an architectural counterweight to the stacked rectangles of the glazing. The carpet’s curling motifs loosen the geometry and prevent the space from stiffening. Overlap, not linear perspective, delivers depth: chair before wall, body before chair, shutters before view. The interior feels shallow enough to honor the canvas yet deep enough for air.

The Window as Threshold

Few painters used windows as consistently and inventively as Matisse in Nice. Here the window is not only a source of light but a conceptual hinge between indoors and outdoors, private body and public promenade. The louvers, cranked open at an angle, stage a modern kind of mediation: the Mediterranean world is welcome but filtered. The stripes of the slats rhyme with the stripes of light that flicker across the carpet and skin. The view is carefully rationed: a thin beach, a cobalt field, a single palm; just enough to aromatize the room with sea air without dissolving it into landscape.

Color Architecture and Temperature

The painting’s color system rests on a clear triad. Cool blues and blue-grays dominate the shutters and out-of-door air; warm reds saturate the carpet; greens—both leaf and olive—concentrate in the drape and palm. The nude’s flesh sits between these poles, modulating from rosy, milk-white passages in the light to cooler gray notes in halftone. Small accents keep the chord in motion: the yellow band of wall between window modules, the umber of the chair’s padding, and the soft black of lashes and mullions. Because each color family appears in multiple zones—blue in shutters and distant water, red in carpet and small interior echoes, green in drape and palm—the room achieves harmony by relation rather than description.

Light Without Spectacle

Light here is bright but disciplined. Instead of a single sheet of sunlight pouring across the figure, Matisse builds a pervasive clarity in which forms turn by temperature and touch. The flesh reads as illuminated from the right, near the window; highlights are withheld or softened so that no single glint distracts from the whole. The shutters, painted with cool, chalky strokes, catch more illumination than cast shadow; their whiteness is tuned cooler than the woman’s skin, preserving the body’s warmth. Shadows are tender and transparent—thin washes of blue or gray—so air seems to circulate around the sitter.

Drawing, Contour, and the Touch of the Brush

Matisse’s line is alive. Around shoulders and thighs the contour thickens and thins as if recording the pressure of a hand on clay. Edges at the window are straighter and darker, anchoring the architecture; edges at the body soften and open, letting the background breathe through. The hand that gathers the drape is rendered with a few rounded passages, almost cartoon-clear, while the face is summarized with a handful of confident strokes: lids, nose bridge, small mouth, the arch of brows. Facture remains visible everywhere—broad, watery passes on the wall and shutters; loaded, swirling strokes on the carpet; drier, scumbled touches on the flesh—so the act of painting becomes part of the picture’s present tense.

Textiles and the Grammar of Pattern

Pattern in Matisse is never mere ornament; it organizes space. The red carpet, with its animated ivory arabesques, does several jobs at once. It warms the lower half of the painting, counters the cool of the shutters, and supplies a rhythm that moves the eye across the floor. Its curling forms echo the curves of knee, hip, elbow, and hair coil, binding figure to ground. The green drape functions as both modest covering and chromatic bridge between the indoor red and outdoor blue. At the far left, a lace or patterned curtain introduces a more subdued motif, reminding us that the interior contains a quiet counter-rhythm to the carpet’s extroversion.

The Nude as Classical Modern

The sitter’s presence is neither coy nor polemical. Seated upright, legs relaxed, eyes alert, she offers a modern answer to the classical nude: assured, unembellished, and local to her room. Matisse declines explanatory gestures or narrative props; the figure is not mythological or allegorical. Instead, she belongs to the same order as the shutters and carpet—an element in a system tuned for balance. Modesty is handled pictorially, not morally, through the drape’s placement and the neutralized modeling of the torso. The result is frankness without exhibitionism, a nude that is “at ease with itself,” to borrow Matisse’s own aspiration for painting.

Spatial Breath and the Viewer’s Loop

The picture rewards a looping path of attention. Most viewers begin at the face—those clear eyes set under concise brows—then slide along the arm to the green drape, follow the red scrolls of the carpet, rise along the chair’s curve, and exit through the window to the blue band of sea. The diagonal shutter slats send the eye back inside, along the window rail, across the pale floor, and home again to the figure. Each cycle reinforces rhymes: the drape’s green answers the palm; the carpet’s white scrolls echo highlights on shoulder and thigh; the mullions’ blue grays steady the posture. Rhythm supplants narrative; the painting sustains attention by keeping it in motion.

A Likely Palette and Materials

The harmony probably issues from a compact palette. Lead white supplies the blinding air of shutters, wall, and flesh lights. Cobalt and ultramarine blues build the shutters and the sea; their admixture with white yields the chalky, sunstruck grays. Yellow ochre and raw sienna warm the chair and a few flesh undertones. Viridian or a blue-leaning green makes the drape and palm; cadmium red or red lake drives the carpet’s field, with ivory white scumbled on top for arabesques. Ivory black remains spare, reserved for lashes, pupils, and a few structural lines. Much of the paint is thin, almost wash-like, allowing the canvas weave to vibrate—an economy that enhances the sensation of light.

Relation to Other Nice Interiors

Seen alongside Matisse’s 1919 interiors—“Nude, Spanish Carpet,” “Nude on a Sofa,” “Reclining Nude on a Pink Couch,” and the balcony scenes with parasols—this “Nude” sits closer to the window. The shutters become co-stars, and the compositional geometry grows bolder. Where the pink couch pictures cultivate plush interiority, here the sea itself leans in. The figure’s upright pose and direct gaze create a tauter energy than the languorous reclines. And the carpet’s red—leaning more to coral than crimson—links to the Riviera’s terra-cotta roofs and light-struck tiles, localizing the nude to place and climate.

Atmosphere and Time of Day

Everything suggests late morning or early afternoon: shutters half-open to fend off glare; sea a clear, ultramarine band; beach a pale strip. The light is dry and architectural, not golden and theatrical. That climate suits Matisse’s practice: he wants clarity rather than drama, sustained attention rather than spectacle. The room breathes at a steady tempo; even the carpet’s extroverted pattern keeps time rather than steals the show.

Meaning Without Anecdote

What, then, does the painting mean? It proposes that human presence and domestic space can be integrated through color relations so perfectly tuned that narrative becomes optional. The nude’s assurance is inseparable from the room’s equilibrium; the shutters’ discipline is inseparable from the sea’s freedom. Matisse’s celebrated wish that painting might be “like a good armchair” for the tired mind is not laziness but ethics: a carefully made calm that steadies perception. “Nude” enacts that ethic without sentimentality.

How to Look

Approach the painting from a moderate distance and let the large relations land: the blue window block against the warm carpet, the flesh’s near-white against the shutters’ cool white, the green bridge of drape to palm. Then step closer and attend to facture: the watery passes on shutters where canvas grain flickers; the carpet strokes, dragged and lifted, that invent arabesques; the delicate scumbles around collarbone and belly where warmth of underpaint meets cool of light. Return to the gaze and you may notice how little it takes—two shaded lids, a small glint—to feel looked at. Finally, let your eye cycle through the room again. The picture deepens by repetition rather than revelation.

Enduring Resonance

“Nude” endures because it compresses a classical subject into a modern grammar of color and line without losing humanity. The figure is a person, not a symbol; the room is a place, not a stage set. The sea outside is not a backdrop but a breath. The painting trusts the viewer’s attention and rewards it with poise. In an art history crowded with dramatic nudes, Matisse offers serenity that is anything but bland: a supple strength built from clear intervals—red to green, blue to white, warm to cool—held in a living contour.